Sinking Feelings

I have never fallen into quicksand, but like most people, I have been anxious about it at least several times in my life. You have too, right? It’s a real thing — you can be sucked down into the soft liquefied Earth unexpectedly, on hikes or on random walks. One of my friends fell into […]

I have never fallen into quicksand, but like most people, I have been anxious about it at least several times in my life. You have too, right? It’s a real thing — you can be sucked down into the soft liquefied Earth unexpectedly, on hikes or on random walks. One of my friends fell into quicksand in Utah, and she is always prepared, so she knew exactly what to do: move your legs slowly and deliberately, in small, tightly controlled steps. Lay down to spread out your weight. Though it’s counterintuitive, get closer to the ground that is consuming you. Do not waste your energy by struggling mightily to get out, because you will only make it worse. Relax your mind and your body, and you will be released. The point is, the way out is not what your instincts might be screaming at you.

Once upon a time, a lot of animals fell into a similar trap and they did struggle. Millions upon millions of them perished in a field of muck, and now we go visit their skulls and rib cages mounted on plinths in the middle of Los Angeles.

The La Brea Tar Pits and Museum is not a place of quicksand, but of something scarier: reeking asphalt, burbling up from a fissure in our planet, the same one that gives us earthquakes in Southern California. The asphalt is made of the remains of past algae and animals, and it will never tire of swallowing life.

The most interesting thing I learned from the La Brea Tar Pits museum came from my friend (and friend of LWON) Katharine Gammon. There are hardly any nocturnal animal fossils in the collection. This took my breath away.

In the absence of the sun, the asphalt leaking up through Earth’s crust would cool slightly and solidify, so nocturnal animals weren’t as often trapped in the sticky tar. When the sun reappeared to warm the world, the asphalt grew gooey again, and crepuscular and diurnal mammals became the main victims. The danger might have been more visible by late afternoon. But during the early morning crepuscular time, leaf litter could have covered softer parts of the tar pits and kept them insulated — and warmer. When lots of large herbivorous mammals were out and about in the dawn hour, they would walk over the soft parts and get trapped.

You would be amazed by the sheer volume of Pleistocene megafauna that scientists have exhumed from La Brea. Mastodons; camels; saber-tooth cats; scimitar-tooth cats; American lions that look like Mufasa and not the panthers that roam here now; dire wolves, real ones; familiar faces like pronghorn, mule deer, and elk; and I lost track of how many others. I looked for Rodents Of Unusual Size, but just saw a few usual-sized ones.

The museum even has a sadly realistic tableau of a mastodon stuck in the tar, sinking down, and calling out to its family on the edge of a pond. Such large beasts, ready for the taking, would obviously have tempted predators and scavengers, but the cats and wolves hoping to feast on the trapped other creatures were trapped too. The museum has several specimens of Smilodon fatalis, the truly awesome saber-tooth cat. Millions of fossils have been disinterred from La Brea. But they include only a few raccoons and other denizens of the night.

To survive the toxic morass of La Brea, large daytime animals would have been better off walking around at night. The sunshine is what exposed them, while the cool darkness of night could have helped them not only hide, but to quietly survive the quagmire. They might have been better off adapting a new strategy to survive. The point is, the way to safety might not have been what their instincts were telling them.

I am not saying we should not struggle at all. We want to fight to survive, and it’s hard to turn off that instinct. I am saying we should think about other ways to struggle, which might be counterintuitive but more effective. Getting safe might look a little different than we expect. The bog will not stop trying to destroy us, so we have to be creative. We have to be lithe and loose, quick-footed, maybe a little sneaky, maybe hew a bit closer to the darkness than we’re used to. There are ways out of every quagmire.

Top image: By the author

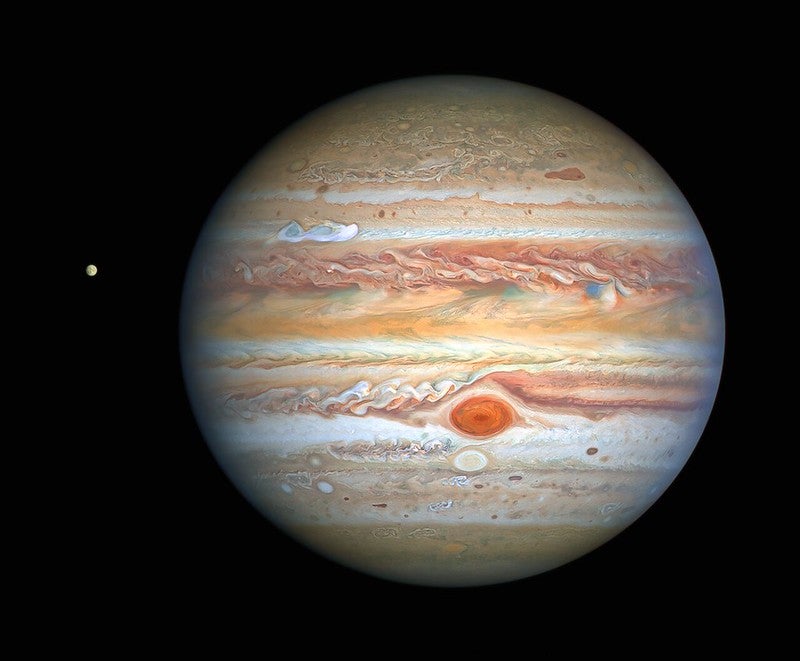

Middle image: Wikimedia Commons

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ec/fc/ecfc9eb9-6049-45ee-8e36-4b616aa8dbba/pxl_20250113_122303511_web.jpg?#)