Seeking yoyu 余裕

There are two ways of thinking about doing more than is necessary. It can become a really useful marketing tactic. When you deliver more than people expect, your overdelivery creates connection. The surprise and delight is remarkable. People talk about it, seek you out and come back for more. Of course, since it’s a useful […]

There are two ways of thinking about doing more than is necessary.

It can become a really useful marketing tactic. When you deliver more than people expect, your overdelivery creates connection. The surprise and delight is remarkable. People talk about it, seek you out and come back for more.

Of course, since it’s a useful tactic, you’re not actually doing more than is necessary. You’re doing the right amount.

The other sort is magical. It’s difficult, ridiculous and offers no obvious commercial benefit.

This sort of effort isn’t always noticed or appreciated by the customer, but that’s okay. It’s the calm, proud and professional approach that serves the maker, regardless of whether it’s worth it to the consumer.

It’s difficult to care enough to do more than is necessary if you are on the assembly line, hustling to make the quarterly numbers or being measured for every keystroke.

Finding the space to care an unreasonable amount is cultural and it often requires a system to nurture that sort of effort. We need room to spare. We need to stop being in such a hurry and focus on the work and the art in a way that’s generative, not frazzled.

The Japanese term for this is yoyu. 余裕 is effort and ease, time and passion.

The characters 余 (yo) means “surplus” or “extra,” and 裕 (yu) means “abundance” or “affluence.”

Yoyu has several interconnected meanings:

- Having spare time or room

- Being relaxed or composed

- Having financial leeway or resources to spare

- Mental/emotional capacity to handle situations calmly

Yoyu produces its own reward.

In a competitive market, it’s easy to see how we slide down the slippery slope of efficiency. The boss usually doesn’t often embrace yoyu, seeking easily measured productivity instead. Make the assembly line a bit faster, change the intensity of the lighting, give out a few bonuses or fire some people.

And scale isn’t the friend of yoyu. If use our resources to expand and amplify, we’ve taken them away from our daily craft. If the project gets bigger when you have slack, slack disappears. Stress arrives.

So why bother?

We’re not machines, or even cogs in a machine. When we are at our best, we’re fully human. Human as producers and as consumers as well.

What’s the point of rushing if we never get anywhere?

Craig Mod has a new book out tomorrow, and I am excited that he’s going to be reaching a larger audience. His walks in Japan have helped people around the world understand the power of yoyu.

The industrial system that we all live in is persistent and powerful. It’s easy to believe that we can outrun it, bring our measured productivity to an impossible 11 and then, at the key moment, veer toward a different way of working and contributing. In fact, we can shift whenever we like. Not completely, not without effort, but we can begin.

Our approach to the work can change from filling our day with tasks to the generous act (for others and for ourselves) of craft. And that shift, amazingly, creates more opportunity, more connection and more satisfaction.

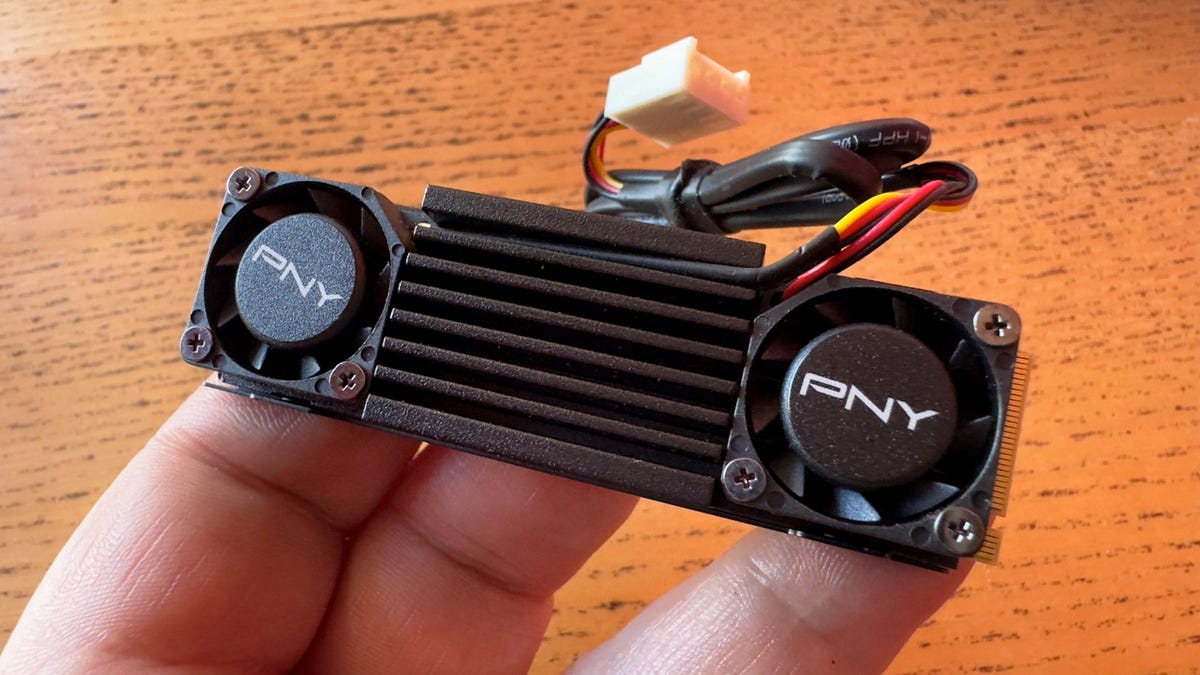

(A handwritten note that came with a $25 order of koji).