Is the 1798 Alien Enemies Act still relevant today?

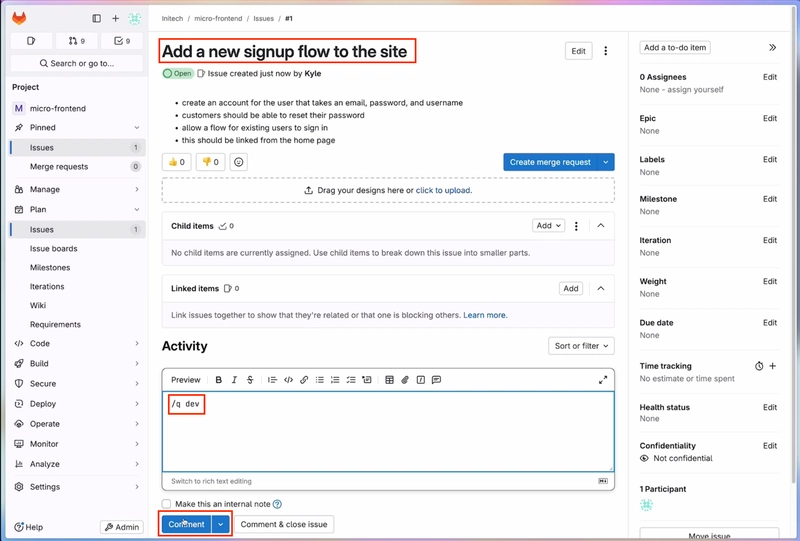

The Trump administration deported of 137 Venezuelan gang members under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. Judge James E. Boasberg ordered flights not to take-off, and, once they did anyway, to return to the U.S. The administration claimed the gang members deported were proxies of the Venezuelan government and therefore that their presence constituted an invasion.

When the Trump administration sent three planeloads of alleged Venezuelan gang members to El Salvador earlier this month, 137 of the 261 passengers were being removed pursuant to the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. That ran into a legal buzz-saw with U.S. District Court Judge James E. Boasberg, on grounds that due process had not been afforded the deportees. He ordered flights not to take-off, and, once they did anyway, to return to the U.S.

The 1798 act was signed into law by President John Adams along with three other bills. They were known collectively as the Alien and Sedition Acts and were enacted by the Adams’s Federalist Party Congress in response to mounting belligerent acts by the French against U.S. ships. War fever was running high in the country over fears that revolutionary France, then at war with Great Britain, would escalate the quasi-war into a full-scale national war with America.

Although Adams had not requested the alien and sedition acts, he signed them into law to appease his frothing Federalist colleagues in Congress. The sedition acts were employed frequently to imprison or fine persons who criticized the U.S. government or its officials.

Adams did not have occasion to trigger the alien enemies measure that would have allowed him, during wartime, to deport those foreign nationals in the U.S. who sided with the French government. A good number of the Jeffersonian Republicans were sympathetic with the French.

While three of the four acts were repealed or expired shortly after Jefferson won the presidency in 1800, the Alien Enemies Act has remained on the books ever since. The Jeffersonian Republicans, under President James Madison, were all too happy to use the act against British citizens residing in the U.S. during the War of 1812.

The Act has only been used two other times in American history — during World Wars I and II. The presidents’ proclamations applied to alien Germans, Italians, Austro-Hungarians and Japanese. The most shameful use, after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, was when President Franklin Roosevelt signed an order to remove all persons of Japanese descent to 10 internment camps inland, away from military areas along the Pacific Coast.

Between 1942 and 1945, 120,00 Japanese residing in America at the time were imprisoned, many of them American citizens. In 1988, Congress apologized for the internments and paid them and their families reparations.

Under the terms of the law, the Alien Enemies Act may be activated by presidential proclamation if the United States is in a declared war or has been invaded, or is under the threat of invasion by any foreign nation or government.

In this month’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act, the dead-of-night deportation of scores of Venezuelans was done without any opportunity for notice or hearing as to whether grounds existed for their removal. The administration claimed the gang members deported were proxies of the Venezuelan government and therefore that their presence constituted an invasion.

These are the questions confronting Judge Boasberg who has pressed government officials for answers. This week, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals voted 2-1 against reversing Boasberg’s order.

Although the act makes clear that any proclamation must be made by the president, Trump told reporters last Friday, on his way out the door for the weekend, “I don’t know when it was signed, because I didn’t sign it.” He went on to explain, that “other people handled it. But [Secretary of State] Marco Rubio’s done a great job. And he wanted them out, and we go along with that. We want to get the criminals out.”

The White House walked-back the president’s recollection shortly thereafter in a statement to CNN, saying that the president had indeed signed the deportation order and that his reference to signing had to do with the signing of the original Alien Enemies Act of 1798. It seems doubtful the president was confusing himself with Adams, who had signed the act in 1798, without using an autopen.

Meantime, Trump, along with a handful of House Republicans who have introduced the requisite resolution, called for Judge Boasberg’s impeachment. In a rare statement from the high bench, Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., invoked the precedent that impeachment is not the appropriate response to disagreeing with a judge’s decision. That should be done through the appeals process.

Whether this case eventually wends its way to the Supreme Court is a matter of conjecture at this point. But if it does, it will be an interesting episode to watch unfold.

Don Wolfensberger is a 28-year congressional staff veteran, culminating as chief-of-staff of the House Rules Committee in 1995. He is author of, “Congress and the People: Deliberative Democracy on Trial” (2000), and, “Changing Cultures in Congress: From Fair Play to Power Plays” (2018).