As ‘bot’ students continue to flood in, community colleges struggle to respond

This story was first published by Voice of San Diego and is reprinted with permission. Community colleges have been dealing with an unprecedented phenomenon: fake students bent on stealing financial aid funds. While it has caused chaos at many colleges, some Southwestern College faculty feel their leaders haven’t done enough to curb the crisis. When the […] The post As ‘bot’ students continue to flood in, community colleges struggle to respond appeared first on The Hechinger Report.

This story was first published by Voice of San Diego and is reprinted with permission.

Community colleges have been dealing with an unprecedented phenomenon: fake students bent on stealing financial aid funds. While it has caused chaos at many colleges, some Southwestern College faculty feel their leaders haven’t done enough to curb the crisis.

When the spring semester began, Southwestern College professor Elizabeth Smith felt good. Two of her online classes were completely full, boasting 32 students each. Even the classes’ waitlists, which fit 20 students, were maxed out. That had never happened before.

“Teachers get excited when there’s a lot of interest in their class. I felt like, ‘Great, I’m going to have a whole bunch of students who are invested and learning,’’ Smith said. “But it quickly became clear that was not the case.”

By the end of the first two weeks of the semester, Smith had whittled down the 104 students enrolled in her classes, including those on the waitlist, to just 15. The rest, she’d concluded, were fake students, often referred to as bots.

“It’s a surreal experience and it’s just heartbreaking,” Smith said. “I’m not teaching, I’m playing a cop now.”

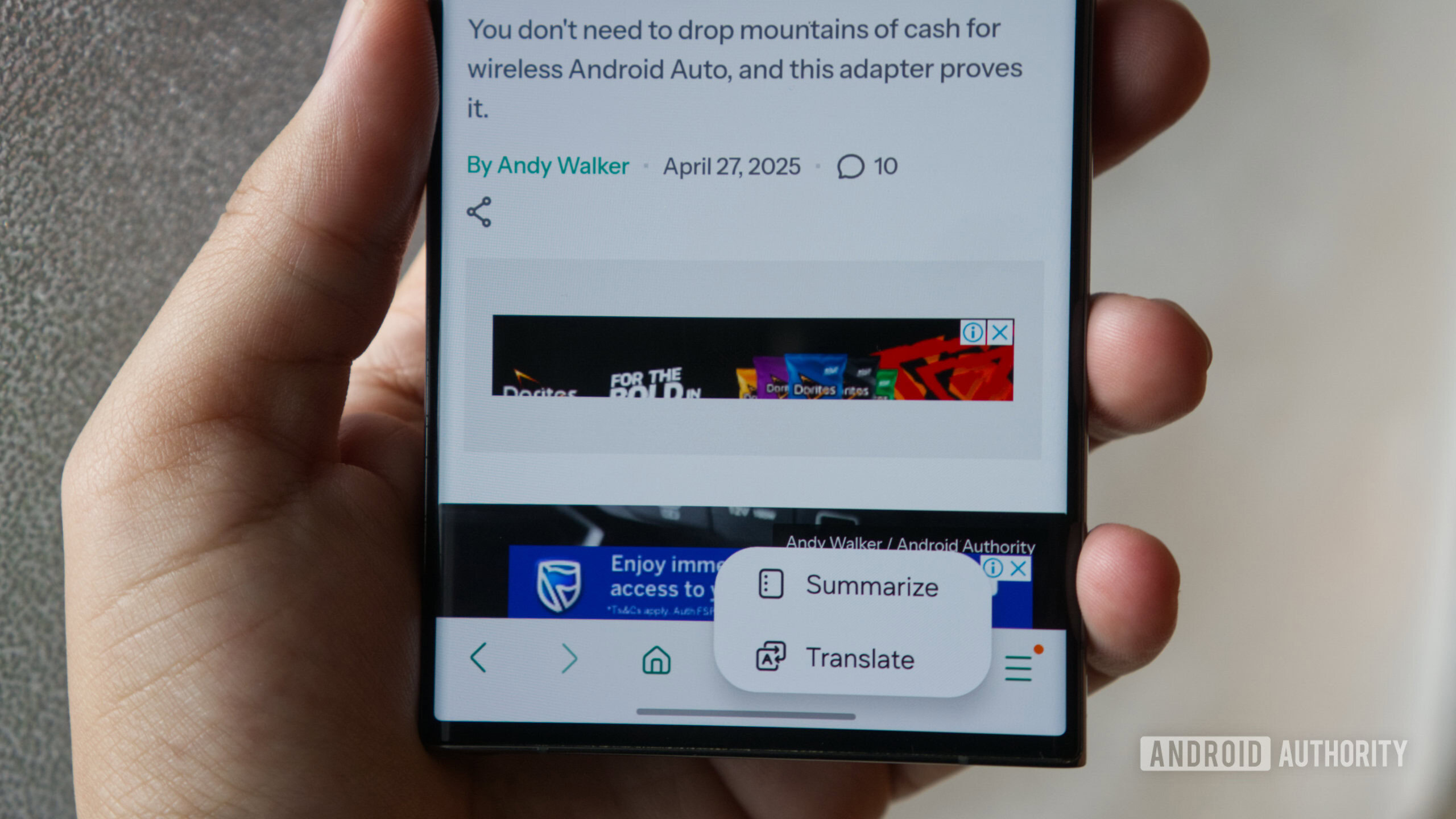

She’s far from the only professor dealing with this trend. Ever since the pandemic forced schools to go virtual, the number of online classes offered by community colleges has exploded. That has been a welcome development for many students who value the flexibility online classes offer. But it has also given rise to the incredibly invasive and uniquely modern phenomenon of bot students now besieging community college professors like Smith.

The bots’ goal is to bilk state and federal financial aid money by enrolling in classes, and remaining enrolled in them, long enough for aid disbursements to go out. They often accomplish this by submitting AI-generated work. And because community colleges accept all applicants, they’ve been almost exclusively impacted by the fraud.

That has put teachers on the front lines of an ever-evolving war on fraud, muddied the teaching experience and thrown up significant barriers to students’ ability to access courses. What has made the situation at Southwestern all the more difficult, some teachers say, is the feeling that administrators haven’t done enough to curb the crisis.

Related: Interested in innovations in higher education? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

Community colleges first started seeing bots managed by fraud rings invade classes around 2021. Those bots seem to generally be real people managing networks of fake student aliases. The more they manage, the more financial aid money they can potentially steal.

Four years later, there are no clear signs it’s slowing down. During 2024 alone, fraudulent students at California community colleges swindled more than $11 million in state and federal financial aid dollars — more than double what was stolen the year prior.

Last year, the state chancellor’s office estimated 25 percent of community college applicants were bots.

Despite the eye-popping sum, state leaders are quick to point out that amounts to a fraction of the around $3.2 billion combined state and federal financial aid disbursed last year. But for many community college teachers, particularly those who teach online courses, the influx of bot students has changed what it means to be a teacher, said Eric Maag, who has taught at Southwestern for 21 years.

“We didn’t use to have to decide if our students were human, they were all people. But now there’s this skepticism because a growing number of the people we’re teaching are not real. We’re having to have these conversations with students, like, ‘Are you real? Is your work real?’” Maag said. “It’s really complicated, the relationship between the teacher and the student in almost like a fundamental way.”

Those teacher-led investigations have become more difficult over the years, professors say. While some bots simply don’t submit classwork and hope they can skate by, they also frequently use AI programs to generate classwork that they then submit. Determining whether a student is a bot tough, can be a confusing task. After all, even real students use AI to do some good old-fashioned cheating in classes.

There are some patterns though. Asynchronous online courses tend to be the heaviest hit. So are classes with large sizes and shorter-term courses, like those that run for only eight weeks. Some teachers also said classes whose names start with letters at the beginning of the alphabet are harder hit as well.

The time spent doing Blade Runner-esque bot detection has also stretched professors thin, said Caree Lesh, a counselor and the president of Southwestern College’s Academic Senate.

“It’s really hard to create a sense of community and help students who are struggling when you’re spending the first couple of weeks trying to figure out who’s a bot,” she said.

Finding the fraudulent students early is key, though. If they can be identified and dropped before the third week of the semester, when Southwestern distributes aid funds, the bots don’t get the money they’re after. It also allows professors to open the seats held by scammers to real students who were crowded out. But dropping huge amounts of enrollees can also be frightening to teachers, who worry that should their classes not fill back up, they may be axed.

Even after dropping the fraudulent students, though, the bot nightmare isn’t over.

As soon as seats open up in classes, professors often receive hundreds of nearly identical emails from purported students requesting they be added to the class. Those emails tended to ring some linguistic alarm bells.

They feature clunky phrases that are uncommon for modern students to use like “I kindly request,” “warm regards,” or “I look forward to your positive response.” Much of that stilted language lines up with what she’s seen from the AI-generated content submitted by bot students.

That mad bot-powered dash for enrollment has left some students unable to register for the classes they need. It has also given rise to a sort of whisper network, where professors recommend students reference them by name when trying to get added to other classes.

Kevin Alston, a business professor who has taught at Southwestern for nearly 20 years, has stumbled across even more troubling incidents. During a prior semester, he actually called some of the students who were enrolled in his classes but had not submitted any classwork.

“One student said ‘I’m not in your class. I’m not even in the state of California anymore’” Alston recalled.

The student told him they had been enrolled in his class two years ago but had since moved on to a four-year university out of state.

“I said, ‘Oh, then the robots have grabbed your student ID and your name and re-enrolled you at Southwestern College. Now they’re collecting financial aid under your name,’” Alston said.

But exactly what colleges like Southwestern will do long-term isn’t entirely clear, at least partly because what they do will have to keep changing. The bots, like the AI technology that often undergirds them, are constantly evolving, leaving some leaders feeling like they’re playing a high stakes game of whack-a-mole. It has also made it difficult for leaders to stay ahead of the bots, said Mark Sanchez, Southwestern’s superintendent/president.

The college has launched an Inauthentic Enrollment Mitigation Taskforce that meets regularly to game out ways to stay ahead of the bots. But as of late, district officials have been more proactive in their bot-attacks. A recent report concluded around 1,600 of the college’s 26,000 enrollees were bots. District leaders then dropped the suspected bots en masse from classes and required them to come in to prove they were real. Few did.

Sanchez has treated exactly how the college has identified suspected bots almost like classified spycraft.

“We have a whole set of parameters that we’re using … But I don’t want anything in print that fraudulent students would be able to see and say, ‘Okay, this is what they’re using. Let’s find workarounds to those parameters,’ because that, because then we would have to start all over again,” he said.

Ultimately, though, he thinks much of the burden to catch bots needs to fall on the state. When students apply to Southwestern, they use a statewide application system. So, by the time the college gets a list of enrollees, it’s already littered with fraudulent students.

“What we’ve asked the state is to put really solid protocols in the CCC Apply system,” Sanchez said.

The California Community College system has put more resources toward detecting fraudulent students, partnering with a handful of tech companies, like ID.me to authenticate students. But that still hasn’t stopped the bots. As of March, scammers had already swindled nearly $4 million in federal and state financial aid.

Tracy Schaelen is Southwestern’s distance education faculty coordinator. In that role she interfaces with many of the college’s online instructors. The current status quo, where teachers spend hours upon hours vetting suspicious students simply isn’t sustainable, she said.

“Teachers are hired to teach. That’s their expertise, and that’s what their students need from them,” Schaelen said.

That solution also can’t be the wholesale elimination of online classes, Schaelen said. Students have increasingly chosen online options, particularly the older, working students community colleges cater to. What’s really needed is a technological solution, she said.

“If we scale back access, then that’s impacting our real students,” she said. “Our goal is to support our real students, so the solution needs to be on the back end, preventing the bots from getting in, not restricting access.”

This story was first published by Voice of San Diego and is reprinted with permission.

The post As ‘bot’ students continue to flood in, community colleges struggle to respond appeared first on The Hechinger Report.

![How to contribute to the Flutter engine [Windows]](https://media2.dev.to/dynamic/image/width=800%2Cheight=%2Cfit=scale-down%2Cgravity=auto%2Cformat=auto/https%3A%2F%2Fdev-to-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fuploads%2Farticles%2F6l3gn3x9ffod81mk92vm.png)