Retrieval in Action: Creative Strategies from Real Teachers

These nine strategies make it quick, fun, and easy to build retrieval practice into any lesson. The post Retrieval in Action: Creative Strategies from Real Teachers first appeared on Cult of Pedagogy.

Listen to the interview (transcript):

This page contains Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

If there is one learning strategy I’ve probably talked the most about on this platform, it’s retrieval practice. In the 10 years since I chose a book called Make it Stick for a book study in the summer of 2015, I’ve been encouraging teachers to add more retrieval practice to their teaching.

But if you’re new here, I’ll give you a very quick overview: Retrieval practice is the act of trying to recall something you learned from memory — by doing things like taking a test on it or using flashcards — instead of just looking at, rereading, or reviewing the information. A big and growing body of research tells us that when we study with retrieval, we learn and remember things much better than we do by other review methods.

While I think we’ve established the value of retrieval as a learning strategy, there’s still room for more practical ways to build it into our teaching. I have encouraged giving frequent quizzes, think-pair-shares, and teaching students to use flashcards, but there are a lot of other ways to do it.

Joining me on the podcast are three cognitive scientists. The first is Dr. Pooja Agarwal, who has been a guest twice already to talk about retrieval practice. Dr. Agarwal has been regularly sharing research and resources on retrieval through her website, retrievalpractice.org, and just recently, she published a book, Smart Teaching Stronger Learning: Practical Tips from 10 Cognitive Scientists.

Each chapter in the book was written by a different cognitive scientist, sharing actionable, evidence-based classroom practices they have used themselves. Two of these authors — Dr. Michelle Rivers and Dr. Janell Blunt — shared theirs on the podcast — you can listen to our conversation in the player above or read the full transcript. The strategies are summarized below.

Whiteboard Activities

Dr. Janell Blunt, an associate professor of psychology at Anderson University in Indiana, uses personal mini-whiteboards with her college students in every class. “I have this suitcase and I wheel it into class — there’s a whiteboard for each student and they they just know it’s their routine.”

Blunt has become a devotee of whiteboards because they work so well and students respond to them so positively. “I don’t know if it’s because doing things on paper feels like it’s it’s busy work or if the whiteboards are just — there’s something really fun about the whiteboards. When they have their whiteboard, they have their eraser in one hand and their pen in the other. And when they make a mistake, it just goes away. It almost is normalizing these mistakes. Like it’s fine; this is part of the process. Whiteboards let them practice retrieval in this really low-stakes, low-anxiety kind of way that is apparently quite fun.”

Another advantage is the fact that they require every student to participate — “something in social psychology we call the diffusion of responsibility. When you walk into the class and say, how are you today? It’s crickets. If I say, give me an example of a noun and like that one kid raises their hand and no one else is retrieving, they’re all waiting for that one kid. But by having the whiteboard, everybody’s coming up with their example.”

Whiteboards have worked so well for Blunt that she’s started setting aside small-group meetings for “radical retrieval,” where the whole class stands and practices retrieval on large, wall-mounted whiteboards for a full hour and 15 minutes.

“So they’re retrieving and I can actually see what they’re doing in the moment,” she explains. “And that’s been a really powerful way to improve learning. And that class, since I started doing that, is a 20 percent improvement in the exam grades. That class always has a wait list now.”

If you don’t have the budget to buy a class set of whiteboards, you can make your own with page protectors, laminated card stock, or by getting panel board cut down at a home improvement store.

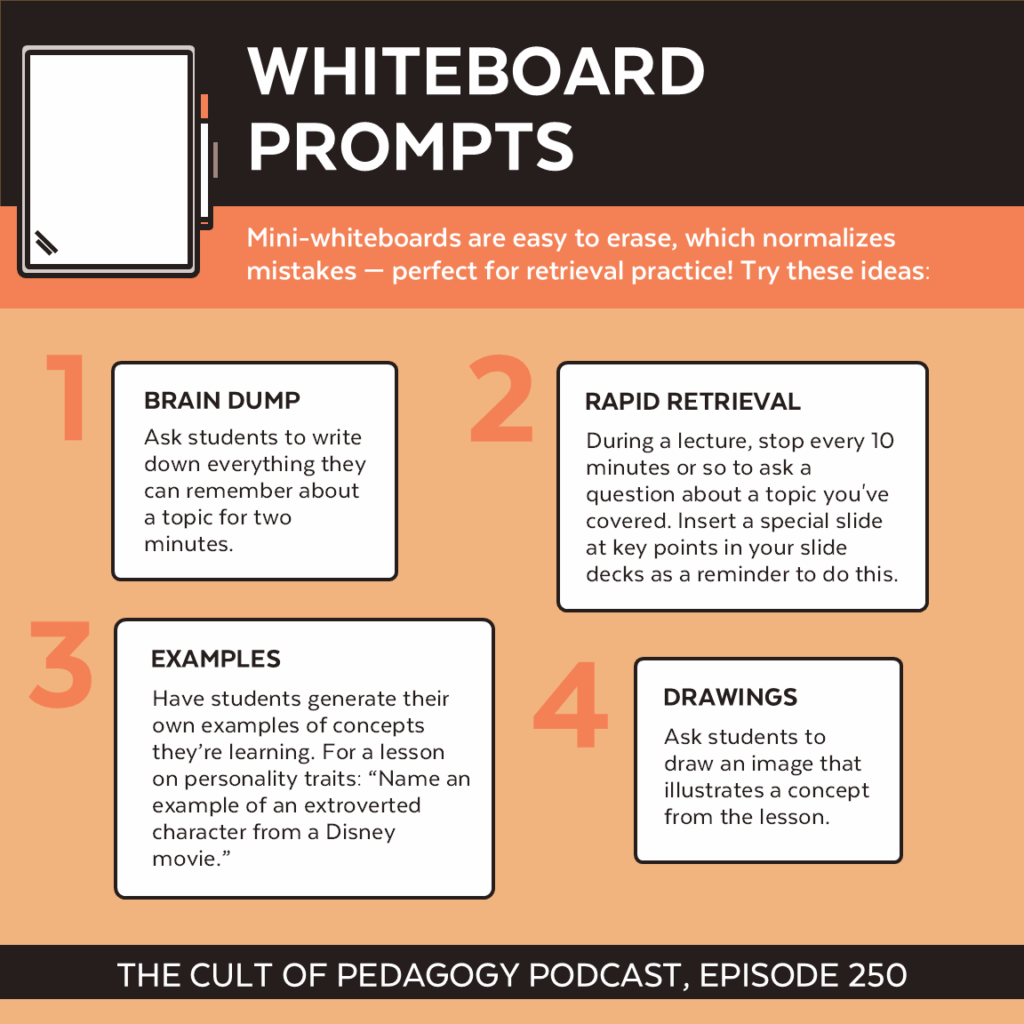

Four Whiteboard Prompts

Although Dr. Blunt says her use of whiteboards includes “anything they want and anything I want,” she has four frequently-used prompts for making retrieval a regular part of her classes:

- brain dump: Ask students to write down everything they remember about a topic for 2 minutes.

- rapid retrieval: During a lecture, stop every 10 minutes or so to ask a question about a topic you’ve covered. Blunt inserts a special slide at key points in her slide decks as a prompt to do this.

- examples: Have students come up with their own examples of concepts they are learning. “In my intro psychology class,” Blunt says, “where we’re talking about personality traits, I might say, come up with an example of someone who’s really extroverted that you’ve seen in a Disney movie. They’re retrieving ‘what is extroverted?’ and then applying it to new knowledge.”

- drawings: Ask students to draw an image that illustrates a concept from the lesson.

Things to Watch Out for When Using Whiteboards

You’ll get the most out of whiteboards if you’re careful about these things:

- not starting early enough: “Set the expectation that you want to hear from students early and often, and they will quickly learn to participate,” Blunt writes in the book.

- students relying on notes: “It’s tempting for students to want to use their notes at first,” Blunt explains. But it’s not retrieval if they have access to the information they’re trying to retrieve. She advises teachers to emphasize the importance of struggle and mistakes as part of the learning. “It’s better to make a mistake and practice retrieval than to use your notes and be right, but not have meaningful learning.”

- using paper instead: Teachers might want to try the same techniques on paper, rather than taking steps to make or buy whiteboards, but Blunt says that would be a mistake. “It doesn’t have that fun feeling. They don’t have that freeing-type zone that the erasers create.”

- assigning points: Blunt strongly discourages assigning points to whiteboard retrieval activities. “We don’t want to say it’s okay to make mistakes and I’m going penalize you for it. You can do completion or participation, but I would avoid assigning points — you don’t want to create anxiety around making mistakes.”

- added social pressure in “radical retrieval”: When Blunt has students do retrieval together on the wall, she says there might be extra social pressure because everyone can see each other’s work. While this can be advantageous, getting students to take the work seriously, it can backfire. “You want just enough to get people motivated, but not so much that people feel anxious,” Blunt explains. “And the good news is we know that retrieval practice reduces anxiety. So we want to keep it that way by not making it high stakes.”

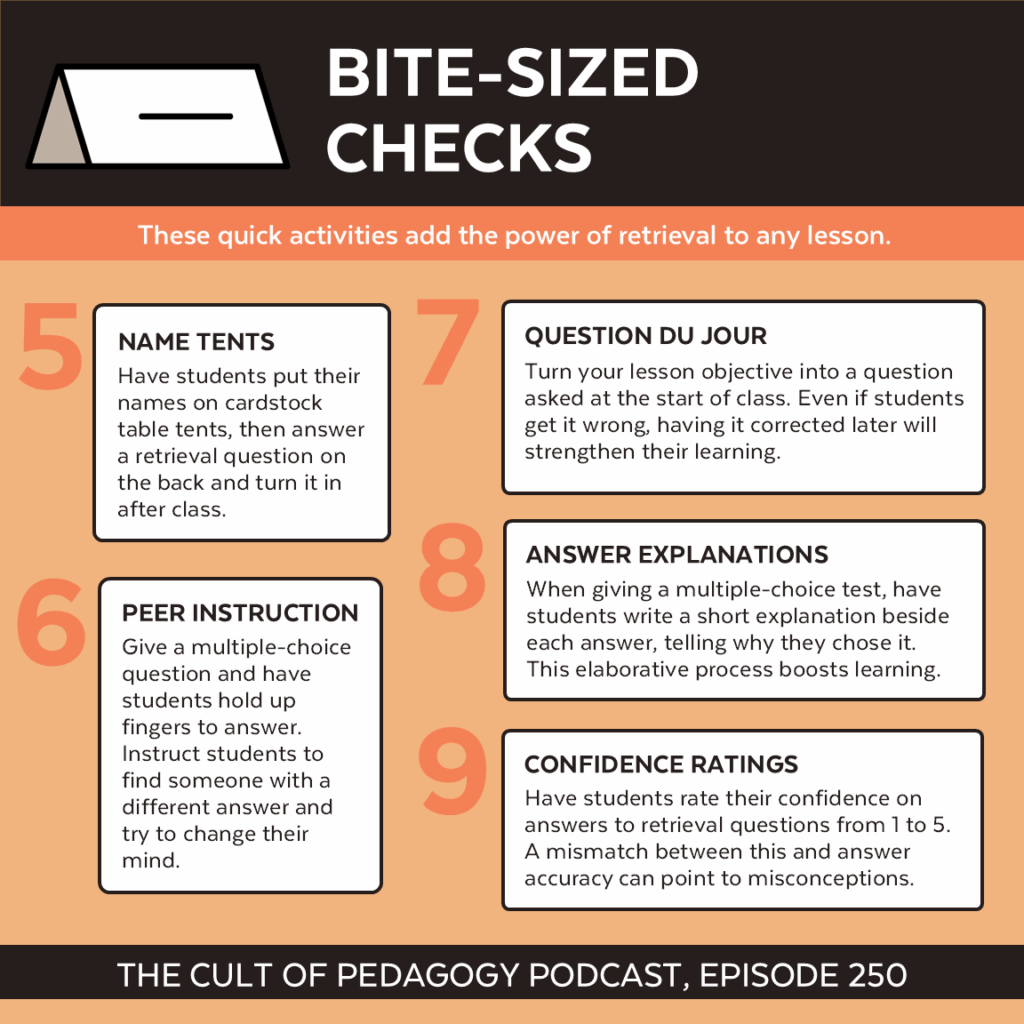

Bite-Sized Checks

Dr. Michelle Rivers, an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Santa Clara University in California, uses a collection of fast, simple strategies to get her students retrieving on a regular basis.

Name Tents

To remember names and manage attendance in larger classes, Rivers has each student write their name on a piece of cardstock and fold it into a tent that they place in front of them during class. To make the tents more useful, students are then asked to answer a retrieval question on the back of the paper and turn it in at the end of class.

“That could be a response to a very broad question,” Rivers explains, “like what is one thing you learned today? or what was the most challenging part of the lesson? For me, this is really helpful for identifying areas of misunderstanding. It’s also a really equitable practice because everyone has to do it; I’m not just relying on the students who will raise their hand and tell me what they learned.”

Peer Instruction

This strategy turns a simple multiple-choice question into a quick collaborative activity.

“Present students with a multiple choice question.” Rivers explains. “Multiple choice is great because you can assess students’ knowledge quickly and equitably. So I’ll have students answer the question on their fingers. Say, hold up a one if they think the answer is A, two if the answer is B, et cetera.”

After students hold up their answers, she instructs them to find a classmate who has a different answer and try to convince them to change their minds. At this point, the correct answer hasn’t been revealed. After talking with their peers, students have a chance to “re-vote” — answering the question again with their original response or a different one.

“They often converge on the correct answer once they talk it through,” Rivers says. “And so that explanation process can be a really effective way for them to to figure out what they know and what they don’t know.

Question du Jour

This one takes something you’re already writing — a daily objective — and turns it into a retrieval opportunity.

“As educators, we’re very used to writing learning objectives,” Rivers says. “But how often do we actually share that with our students? Maybe we say, here’s the agenda for the day. But just a simple tweak to engage retrieval would be to frame it as a question, or question of the day.”

For a lesson on memory, for example, Rivers might start the day by asking students to answer a question like, “Why do we remember some things for a long time and forget other things very quickly?”

“That’s going to guide our discussion for the day,” she explains. “Getting them thinking can kind of prompt that curiosity; it’s kind of like giving students the menu before the meal comes. And even if they answer incorrectly — you might think intuitively that that would be harmful for their learning. But research shows the opposite. As long as you correct them and give them the answer during the lesson, having given the wrong answer might actually be a great cue for them to remember, Oh right, I was wrong about that. It felt like I was right, but no, I was wrong. Now I’m going to remember what my instructor said or what I read in the book or the video we watched or whatever it was that corrected my knowledge.”

Answer Explanations

“A lot of educators, including myself, use multiple choice tests because they’re really efficient measures of learning,” Rivers says. “But they’ve also been criticized because you can rely purely on recognition rather than engaging these deeper retrieval, elaborative processes that we know really help with lasting learning.”

So what Rivers does is has students write short explanations next to their multiple-choice questions.

“So basically, why did you pick that response?” she says. “And students can interpret that however they want. It could be why they eliminated the other responses. Or it could be, oh I remember learning this in class.”

Rivers says recent research has found that students are more likely to pick the correct answer when they are asked to provide an explanation. And even if the teacher doesn’t have time to read all of the responses, there’s still a benefit to the learner. “They’re going to benefit from those elaborative processes of trying to explain their answer.”

Confidence Ratings

This metacognitive strategy can be layered on top of any of the other strategies here, including the whiteboard prompts: Whenever students respond to a retrieval question, ask them to rate their level of confidence in their answer from one to five — one if they’re not confident, five if they’re very confident. When there’s a mismatch between a student’s confidence level and the accuracy of their answer, that’s an opportunity for identifying misconceptions and areas for further study.

“They might realize, oh, I was super confident, but I was totally wrong, which can be really good for a restudy tool,” Rivers says. “Like, okay, definitely going to need to go revisit things and make sure that I’m not making those errors when it it really is a high-stakes assessment.”

Learn More

- To learn more about retrieval practice, visit Dr. Pooja Agarwal’s site retrievalpractice.org, and you can find free resources from Smart Teaching Stronger Learning here.

- Dr. Janell Blunt teaches a course on LinkedIn Learning called Strategies to Learn and Upskill More Effectively

- Dr. Michelle Rivers runs a blog called cogbites that offers bite-sized research summaries in cognitive science.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.