The secret to Warren Buffett’s stock-picking success: He knew how to change his mind

The Berkshire Hathaway guru's willingness to adapt helped him earn billions from Apple and donate billions to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

On July 3, 2006, Warren Buffett drove to the U.S. Bank branch in downtown Omaha, walked in, went downstairs, and opened his safe-deposit box. He removed a piece of paper, a certificate for 121,737 shares of Berkshire Hathaway stock. It was worth about $11 billion. The money from the sale of those shares, a fraction of his Berkshire holdings, would be the first tranche in his program to give away virtually all his wealth.

That bank visit was a bookend in Buffett’s life, a fittingly financial signal event in the life story of the man widely regarded as the world’s greatest investor. He told Fortune at the time that it reminded him of a visit to that same bank, then called Omaha National, almost 70 years earlier, an event that in retrospect seems the other bookend in Buffett’s financial life. He was 6 years old. His father set up a savings account for him and put $20 in it.

Between those two bank visits, Buffett created Berkshire Hathaway, made it America’s largest conglomerate, and became globally famous. On May 3, he signaled the end of that remarkable run, announcing that he would hand the CEO reins to his longtime lieutenant Greg Abel at the end of this year.

Buffett will be leaving with an unmatchable record. He achieved a 19.9% average annual return to Berkshire shareholders from 1965 through 2024, or about 5.5 million percent in total for original investors, including himself. By the 2020s his wealth would have reached over $200 billion, making him the world’s richest person—if he hadn’t given away so much of his stock.

Thus the obvious questions that have transfixed investors for decades: How did Buffett grow $20 to well over $200 billion? Why weren’t others able to do it? How did he find the secret? What is the secret?

It’s tempting to look for answers in the aphorisms Buffett coined so memorably: “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.” “It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.” “Only buy something you’d be perfectly happy to hold if the market shut down for 10 years.”

He believed them intensely, but they aren’t the key to his success. The key is, he never stopped seeking the key. When asked to explain his success, he often said it was simply that he was “rational.” It sounds so easy. But rational people change their beliefs when reality dictates, and most of us find doing so excruciatingly hard.

Buffett could do it. His maxims sound as if he found them engraved on a stone tablet, but in reality he learned them. He was just a kid when he started learning the hard way. As a teenage investor he tried technical analysis, studying charts of stock prices looking for “candlesticks” or “bearish divergence signals.” That didn’t work, so he gave it up. He tried what nearly every investor tries, timing the market, choosing just the right moments to buy and sell. That didn’t work either, so he left it behind.

He even made irrational, emotional decisions. At age 11, in 1942, he bought his first stock: three shares of Cities Service Preferred for himself and three shares for his sister Doris. (Cities Service was the oil and gas company now known as Citgo.) The price quickly dropped. When it finally recovered and rose just above the price he had paid, he sold—and the price kept rising, soon quintupling. He never forgot that he should ignore the price he had paid, which he couldn’t change, and focus only on the company’s future. He learned also that if he was going to invest someone else’s money, he had better be highly confident he could do it well. His biographer, Alice Schroeder, wrote that Buffett “would call this episode one of the most important of his life.”

Most people find it excruciatingly hard to change their beliefs when reality dictates. Buffett could do it.

Years later, as a successful fund manager with much more at stake, he dared to change his philosophy of investing yet again. At Columbia Business School from 1949 to 1951, Buffett had become a devoted student of Benjamin Graham, coauthor of the famous investing guide Security Analysis, who advised buying stocks only at extreme bargain prices based on financial ratios. But Buffett’s business partner, Charlie Munger, convinced him that fundamentally good businesses could be worth buying even if they weren’t screaming bargains. In 1972, Buffett bought See’s Candies for three times book value—heretically expensive, to Grahamites—and never looked back. See’s remains a great performer for Berkshire.

He never stopped challenging his beliefs. He saw the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s for what it was and said so. He wouldn’t invest in internet stocks, he explained, because they were impossible to value. Silicon Valley cheerleaders shook their heads smugly, lamenting that old Warren had let the tech revolution pass him by.

When the crash hit, he had every right to be smug himself, but he later found a much better riposte. In 2016 he started buying into tech royalty: Apple, which grew to be the largest holding in Berkshire’s stock portfolio.

Wall Street analysts had often warned that Apple stock was overpriced. Ben Graham would have disapproved. But Buffett saw an incredibly good business—enormously profitable, with a huge competitive “moat” around its products. He told his shareholders in 2023, “It just happens to be a better business than any we own.” (Berkshire sold the majority of its Apple shares over the course of 2024, but it remained the company’s biggest equity holding at the end of the year.) At Berkshire’s recent annual meeting, Buffett said, “I’m somewhat embarrassed to say that [Apple CEO] Tim Cook has made Berkshire a lot more money than I’ve ever made for Berkshire Hathaway.”

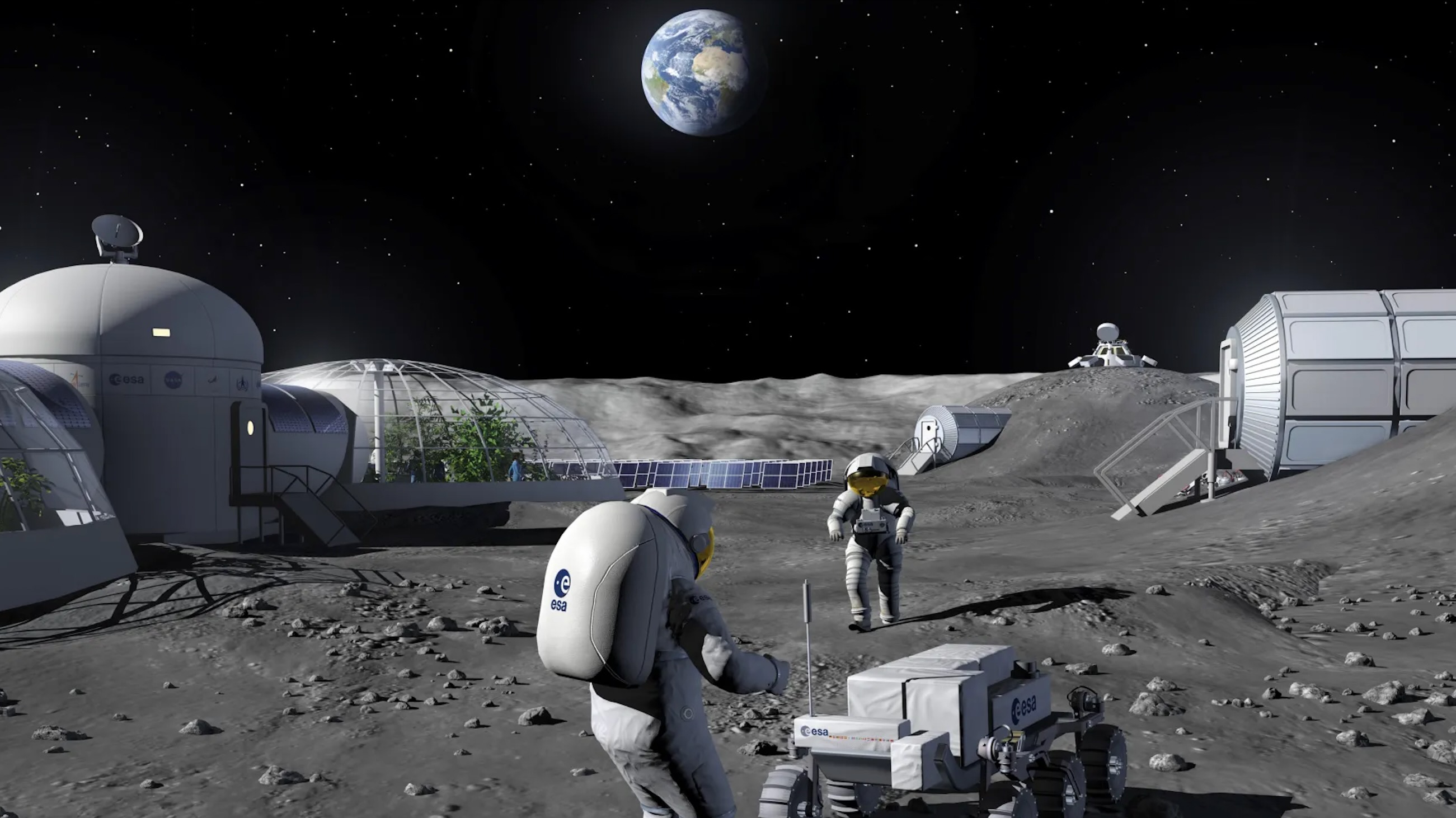

While always rethinking how to make money, Buffett was also rethinking how to give it away. For years he had planned to start donating his wealth (“more than 99%” of it, he said) at his death through a foundation he had set up. But in 2006, at 75, well past the age when most CEOs have retired, he changed his mind. He would instead start donating it immediately, mostly to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with smaller amounts going to his original foundation and the foundations set up by each of his three adult children. (Bill Gates is now making a remarkable commitment with the help of those donations, and with Buffett’s blessing; see "Bill Gates’ $200 billion moonshot: Inside the biggest bet on humanity a philanthropist has ever made")

Why the shift? Once again he shaped his views to fit reality. He had been a good friend of the Gateses’ for 15 years and admired their work at the foundation, which was big enough to handle the enormous sums he would be sending to them. They were also significantly younger than himself. His conclusion, as he explained it to Fortune, was pure Buffett: “What can be more logical, in whatever you want done, than finding someone better equipped than you are to do it?”

That’s what brought him to his safe-deposit box in downtown Omaha, by himself, removing a piece of paper worth $11 billion. He would soon send it to the Gates Foundation. We cannot know his emotions at that moment, as he said goodbye to a significant portion of his life’s work, but it’s difficult to believe that he swallowed hard or trembled. More likely he was smiling.

Three great pivots

Warren Buffett has been better than most at changing course—a fact that explains both his success and his longevity.

Giving up "cigar butts"

Buffett began his career as a disciple of Benjamin Graham, who recommended buying stocks only at rock-bottom prices. But Buffett’s business partner, Charlie Munger, convinced him that some strong companies were worth buying even when they weren’t bargains— paving the way for some of Buffett’s best investments.

Catching up on tech

Even as he built a peerless track record, Buffett avoided investing in tech companies, arguing that their future value was impossible to estimate. But he eventually came to recognize Apple, under CEO Tim Cook, as a traditionally great business with a huge competitive “moat.” It became one of Berkshire Hathaway’s top-performing holdings.

Giving to the better giver

Buffett had long planned to give away most of his wealth after his death. But the accomplishments of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation changed his mind—and attracted some $40 billion of his money. As he told Fortune, “What can be more logical, in whatever you want done, than finding someone better equipped than you are to do it?”

This article appears in the June/July 2025 issue of Fortune with the headline "Warren Buffett's secret to success: He knew how to change his mind."

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

![[FREE EBOOKS] Modern Generative AI with ChatGPT and OpenAI Models, Offensive Security Using Python & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

.webp?#)