The Crisis of American Leadership Reaches an Empty Desert

Photographs from the humanitarian disaster in Sudan and Chad

Introduction by Anne Applebaum

In Tiné, a barren desert town in eastern Chad, the first humanitarian crisis of the post-American world is now unfolding. Thousands of people fleeing the civil war in Sudan’s Darfur region have recently arrived there after enduring long journeys in relentless, 100-degree heat. Many have nothing—they report being beaten, robbed, or raped along the way—and almost nothing awaits them in Tiné. Due in part to the Trump administration’s devastating cuts to foreign aid, only a skeleton staff of international humanitarian workers are on hand to receive them. There are shortages of food, water, medicine, and shelter in Tiné, and few resources to move people anywhere else.

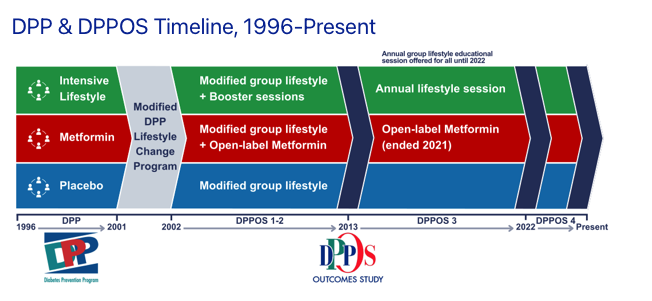

Several months ago, I was reporting in Sudan with the photographer Lynsey Addario. She recently returned to the region and spent several days photographing and speaking with some of the people who are streaming into Tiné. According to aid workers on the ground, more than 30,000 people have arrived there since regional fighting intensified in mid-April, and more than 3,500 are now arriving every day. The photos below capture the desperation of people with nowhere to go, the absence of infrastructure to help them, the desolation of the empty desert.

Most of the people in Tiné and nearby towns are coming from Zamzam, a famine-stricken camp for displaced people in North Darfur. Aid trucks carrying food have long had difficulty reaching Zamzam, thanks to ongoing violence, bad roads, and the Sudanese government’s reluctance to let international organizations operate in areas controlled by its rivals. Over the past few weeks, the Rapid Support Forces, the militia that is the Sudanese army’s main antagonist, raised the stakes further. The RSF tightened its siege of El-Fasher, the largest city in North Darfur, and began shelling Zamzam itself.

The core of the RSF consists of Arabic-speaking nomads, once known as the Janjaweed, who have long been in conflict with the non-Arab farmers in this part of Sudan. Their lethal rivalry is not a religious dispute—both sides are overwhelmingly Muslim—and the ethnic differences are blurry. Nevertheless, refugees in Tiné say RSF soldiers are interrogating people escaping from Zamzam and El-Fasher, and murdering men who look “African” instead of “Arab,” who speak the wrong language or who come from the wrong tribe. “If your language is Arabic, they will let you go,” a woman named Fatima Suleiman recounted. Those who did not speak it, she said, were murdered on the spot. Her dark-skinned son, Ahmed, a student who knows some English, was spared because he speaks Arabic too, though his friends were not as fortunate. He watched them get gunned down.

In theory, the Trump administration still supports emergency humanitarian aid. But in practice, the cuts to logistics and personnel, the abrupt changes to payments, and the associated chaos have hampered all of the international humanitarian organizations working in Tiné and everywhere else. The Chadian Red Cross lacks transport for the wounded. The World Food Program’s supplies are unreliable because support systems have been cut. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees is cutting staff due to budget constraints. Jean-Paul Habamungu Samvura, who represents UNHCR in eastern Chad, said that in his 20-year career, he could not recall refugees ever being offered so little.

“Our big donor is the U.S.,” Samvura said. But in February, UNHCR was instructed to alter its services. “Things we are used to seeing as lifesaving activity, like providing shelter, are no longer considered lifesaving activity,” he explained. That leaves his team with an unsolvable problem: “Where to put people at least to give them a bit of shading.” Some of his staff have been told that their jobs will end as soon as June, but the crisis will not end in June.

Local Sudanese groups, part of a mutual-aid movement called Emergency Response Rooms, are collecting donations from overseas and have begun offering meals to refugees, as they do all over Sudan. But if the number of displaced people continues to grow as the scale of the disaster expands, these volunteers will also need more resources, if only to ensure that everyone in Tiné eats a meal every day. Eyewitnesses report people dying of thirst on the way to Tiné, and malnourished children arriving among the refugees.

This is a dramatic moment in a devastating war. More people have been displaced by violence in Sudan than in Ukraine and Gaza combined. Statements about Sudan are regularly made at the UN and in other international forums. And yet the people in these photographs seem to have been abandoned in an empty landscape. As the United States withdraws and international institutions decay, their ordeal may be a harbinger of what is to come.