The Big Focus on Federal Judges Is Not a Good Sign

Focusing on them as personalities is a step away from a government of laws and toward one of men and women.

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

One indicator about the health of the nation is how many lower federal judges a regular news consumer can name—and reel off biographical details about—without much hesitation.

By now, many know James Boasberg, who is handling the matter of deportation flights to El Salvador. He is merely the highest-profile in a crew of newly famous judges: Paula Xinis is overseeing Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s case. Fernando Rodriguez Jr. rejected the Trump administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act. J. Harvie Wilkinson scorched the White House over due process. Beryl Howell threw out Donald Trump’s executive order targeting a liberal law firm. Tanya Chutkan was set to preside over Trump’s trial on charges of 2020 election subversion, though the case was dismissed first.

“At any given time in our history, the public writ large doesn’t know of a single lower-federal-court judge,” the legal scholar and retired federal judge Michael Luttig told me. (Luttig has also contributed to The Atlantic.) “Fast-forward to today: Judge Boasberg is a federal district-court judge, and Donald Trump puts him on a marquee in front of the world and trashes him.”

Luttig might be exaggerating the public’s ignorance of federal judges slightly, but these jurists have suddenly become major figures in the news, many of them for nothing more than doing their job: hearing cases, trying to earnestly interpret the law, and then issuing an opinion. The desire of many media organizations to illuminate their personalities, and the desire of audiences to learn about them, is understandable, especially as Trump’s attempts to test the rule of law have made the courts into more heated battlegrounds. Also understandable is the impulse among Trump critics to lift up as heroes judges who withstand pressure. Nor should any public official be beyond scrutiny.

But watching the focus shift from law, precedent, and evidence and onto the judges themselves has been unnerving. The problem is not merely the celebrification of politics that has in recent years afflicted the executive and legislative branches, and to some extent the U.S. Supreme Court as well. In the context of the judiciary, the danger is especially acute. John Adams wrote in 1776 that “the very definition of a Republic, is ‘an Empire of Laws, and not of Men.’” Focusing on the judges as personalities is a step away from a government of laws and toward one of men and women.

It also serves Trump’s purposes. He would much rather focus on attacking the judges and claiming that they hate him or are anti-American than on the fairly clear findings in case after case that his administration has overstepped its power and the bounds of the Constitution. Perhaps it’s no surprise that when Time asked Trump about that Adams quote recently, he was unfamiliar.

“The last thing that any federal judge wants to do, frankly with anyone, is seek out controversy,” Luttig told me. But “of course this is the way the president wants it. The last thing he wants to talk about is the law, and he wants to demonize the individual judges.”

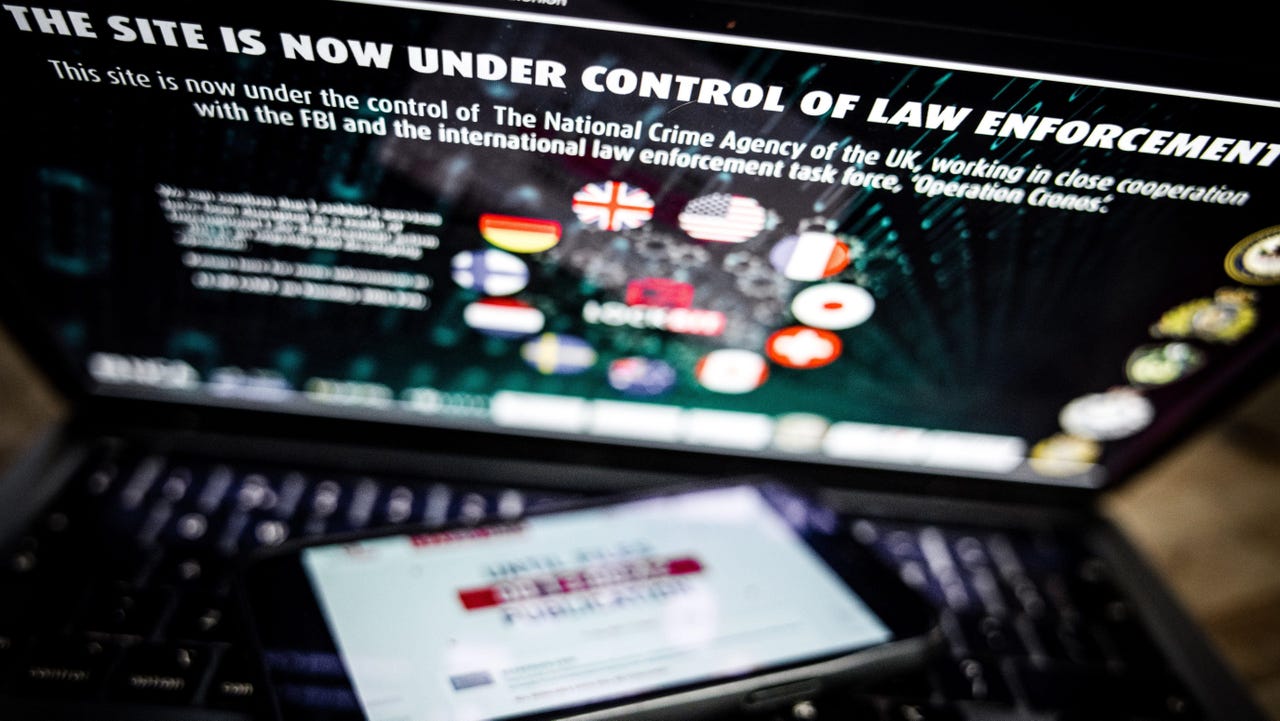

By attacking nearly every judge who rules against his policies as biased—even those that come from judges he nominated to the bench—Trump delegitimizes the court system, allowing himself to overstep further next time and possibly laying the groundwork to disregard court rulings. The attacks also risk physical harm against judges, who have faced a growing number of threats in recent weeks. Trump may merely wish to bully judges, but his vilification of public figures has in the past resulted in some of his supporters taking up violence.

Judges are not, and should not be treated as, purely objective and rational beings who are above politics. Starting in the mid-20th century, conservatives began complaining about “activist judges” who they believed were driving a social agenda from the bench. More recently, liberals have embraced a similar critique. Leah Litman, a law professor at the University of Michigan, argues in her forthcoming book, Lawless, that the Supreme Court has abandoned legal interpretation for conservative grievance.

“It’s healthy and important for news coverage to capture the reality that judges are people too,” she told me. “Their legal rulings are going to be influenced by their life experience and their worldview and the political parties that appointed them, and to not acknowledge that in some way feels misleading.”

This means, for example, that noting who nominated a judge can be valuable—especially, as in the Rodriguez example, when a Trump-nominated jurist rules firmly against the president. It also means that when judges make repeated decisions that fly in the face of precedent—such as Aileen Cannon, the Trump-appointed judge who repeatedly ruled in his favor in the case over his hoarding of sensitive documents at Mar-a-Lago—they deserve scrutiny.

Another unfortunately prominent federal judge is Matthew Kacsmaryk, a Trump-appointed district-court judge in Texas. Conservative activists have homed in on Kacsmaryk, because he reliably rules in their favor and because, thanks to the oddities of judicial districts, they can consistently get their cases before him specifically and then persuade him to issue nationwide injunctions. In his most notable case, he attempted to block mifepristone, an abortion drug, in a long-shot challenge to its FDA approval. The substance of Kaczmaryk’s rulings deserves criticism—the Supreme Court had no patience for his mifepristone ruling—but even here, as Nicholas Bagley wrote in The Atlantic, the larger problem is the system that allows for such judge-shopping and national injunctions. (Now that judges are issuing nationwide injunctions against the Trump administration, some conservatives are starting to see the wisdom of this point.)

If the newfound prominence of these judges were a sign of improved civic engagement, perhaps that would be reason for applause. But this is unlikely, given continued public ignorance about the Supreme Court. A poll last year found that a majority of the public had never heard of or knew little about any of the justices besides Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh. Americans are hearing both too much about the courts, and far too little.

Related:

Here are four new stories from The Atlantic:

- Why this India-Pakistan conflict is different

- The actual math behind DOGE’s cuts

- Trump’s inevitable betrayal of his supporters

- Now is not the time to eat bagged lettuce.

Today’s News

- Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost was elected as the pope. He will be the first American to serve in the papacy.

- U.S. President Donald Trump and U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced a trade deal between their countries, but some of the details still need to be finalized.

- Trump withdrew his nomination for surgeon general and picked the author and wellness influencer Dr. Casey Means as a replacement last night.

Dispatches

- Time-Travel Thursdays: How will the new pope shape the Catholic Church and the world? Fitting popes into borrowed political labels such as left and right, liberal and conservative doesn’t always age well, Luis Parrales writes.

- Work in Progress: Donald Trump seems to be ceding the future to China while emulating its past, Derek Thompson writes.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

We’re All Living in a Carl Hiaasen Novel

By Amy Weiss-Meyer

Nothing about Carl Hiaasen’s outward appearance suggests eccentricity. I’ve seen him described as having the air of “an amiable dentist” or “a pleasant jeweler” or “a patrician country lawyer.” He is soft-spoken, courteous, and plainly dressed. The mischief is mostly detectable in his eyes, which he’ll widen to express disbelief or judgment, or cast sideways to invite a companion to join him on his wavelength, raising his brows for effect.

Every so often, he’ll say something that serves as a reminder of why his name has become synonymous with Florida Weird.

More From The Atlantic

- The MAHA takeover is complete.

- The bliss of a quieter ego

- Trump’s weak position on trade

- How spying helped erode American trust

Culture Break

Dress up (or don’t). School spirit days are a totally unnecessary way to stress parents out, Julie Beck writes.

Watch. Taskmaster (streaming on YouTube and Pluto TV) is an oddball British comedy show that David Sims thought he’d hate (and has since come to love).

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

![Ditching a Microsoft Job to Enter Startup Hell with Lonewolf Engineer Sam Crombie [Podcast #171]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1746753508177/0cd57f66-fdb0-4972-b285-1443a7db39fc.png?#)