See No Evil: Roberto Minervini on “The Damned”

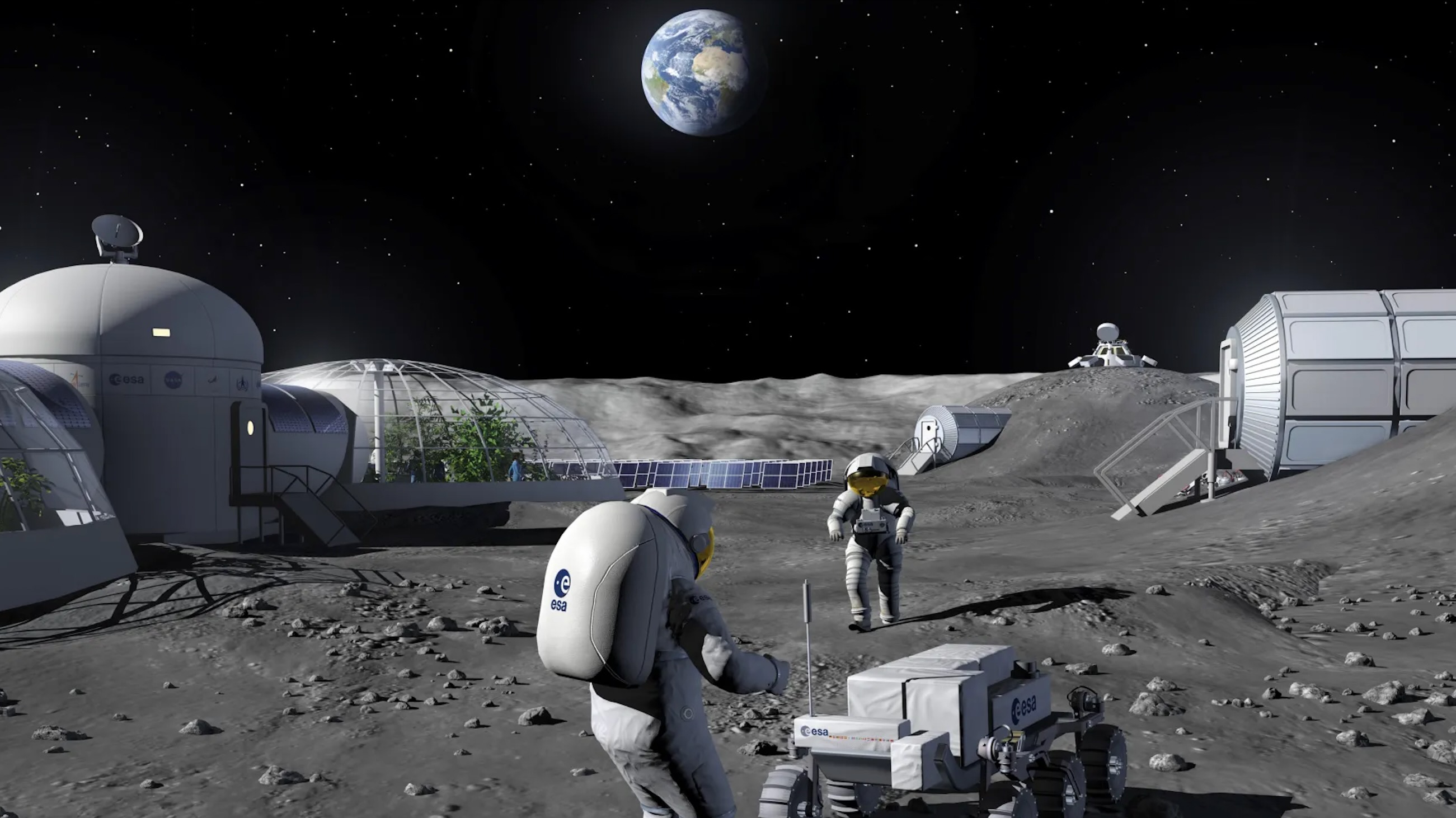

The Damned (Roberto Minervini, 2024).The Damned (2024) is director Roberto Minervini’s first fiction film, but like each of the Italian filmmaker’s previous five features, which seamlessly integrated dramatized elements into otherwise observational frameworks, it feels plainspoken and intimate, as if torn from the fabric of reality. What’s remarkable is that Minervini has achieved this not by telling a contemporary story or reimagining a recent event, but by returning to the past. Set in 1862, The Damned is an American Civil War drama that unfolds like a documentary, a full-fledged period piece that speaks to modern-day issues without betraying the integrity of its setting.An opening title card sets the scene: In the dead of winter, the Union army has sent a company of volunteer soldiers to the western territories to patrol the region’s unchartered borderlands. Preceded by an image of wolves devouring a deer carcass, it’s an introduction that doubles as a synopsis; almost no further information about the war or the lives of these characters will be provided. Instead, the film charts a more existential path as it follows this group of men into unknown territory, where their sense of duty will be tested both morally and spiritually—matters that slowly come to dominate the majority of the conversations, which are otherwise concerned with the mundane and the prosaic. Indeed, few war films have ever been less focused on the machinations of warfare, let alone combat. There’s only one battle sequence in The Damned, and the fighting is depicted almost impressionistically, in a succession of long takes that track individual members of the troupe as they flee gunfire from an unseen enemy.Shot largely at dusk by cinematographer Carlos Alfonso Corral, the film is burnished in a kind of muted glow, lending an appropriately elegiac air to a narrative centered on questions of faith and mortality. As in Minervini’s nonfiction work—which has dealt exclusively with various rural communities and subcultures in the American South, where the director lived for almost two decades after moving to the US in 2000 (he’s now based in New York)—these are themes brought forth by his performers (some of whom were featured in Stop the Pounding Heart, 2013), whom he calls on to contribute ideas and character details from their own lives. This collaborative approach reached its apotheosis with The Other Side (2015) and What You Gonna Do When the World's on Fire? (2018), films that fearlessly documented contemporary race relations from opposite ends of the sociopolitical divide. With The Damned, Minervini continues this project by other means, tracing issues of class, oppression, and discrimination to a watershed moment in American history that, period trappings notwithstanding, feels frighteningly current in an era of extreme political polarization.Shortly after The Damned’s premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, where Minervini picked up the Best Director prize in the Un Certain Regard sidebar (in a tie with Rungano Nyoni, for On Becoming a Guinea Fowl), we met to discuss the film’s contemporary resonances and how his idiosyncratic approach to fiction helped alleviate the weight of written history for both himself and his actors. A year later, the film is making its US theatrical debut.NOTEBOOK: Can you talk about the impulse to work more directly in fiction with this film? Is this something you had always wanted to do? ROBERTO MINERVINI: Yeah, I had been wanting to do it for a while. I wanted to step into a territory where I could digress on certain topics, and move freely from past to present, without having to abide by any codes. I wanted to see how it felt, while also keeping to certain aspects of my established approach, which stems from individuals and what they bring to the table and how they influence the writing process. I wanted to apply this in a fictional realm where I could enjoy a different kind of freedom—not necessarily a formal freedom, just because there are dramaturgical codes in fiction, but an ethical freedom, where I could digress as much as I wanted from factual truths. NOTEBOOK: What was your conception of the Civil War before moving to the US? MINERVINI: The US Civil War is known globally as the war that put an end to slavery. It’s seen as the quintessential war of Good vs. Evil, with the Union being the good guys. That’s how I learned it, back in Italy. But my interest in this chapter of US history has less to do with me moving to the US than with me moving to the South. I spent fourteen years living in Texas, digging deep into the past and present, studying history and documenting several local communities. My main drive was to come to a more thorough understanding of the reasons for the distrust towards the federal government, which runs very deep in the South. And some of those reasons can be found in the nineteenth century North–South divide. NOTEBOOK: Did your experience with The Other Side in partic

The Damned (Roberto Minervini, 2024).

The Damned (2024) is director Roberto Minervini’s first fiction film, but like each of the Italian filmmaker’s previous five features, which seamlessly integrated dramatized elements into otherwise observational frameworks, it feels plainspoken and intimate, as if torn from the fabric of reality. What’s remarkable is that Minervini has achieved this not by telling a contemporary story or reimagining a recent event, but by returning to the past. Set in 1862, The Damned is an American Civil War drama that unfolds like a documentary, a full-fledged period piece that speaks to modern-day issues without betraying the integrity of its setting.

An opening title card sets the scene: In the dead of winter, the Union army has sent a company of volunteer soldiers to the western territories to patrol the region’s unchartered borderlands. Preceded by an image of wolves devouring a deer carcass, it’s an introduction that doubles as a synopsis; almost no further information about the war or the lives of these characters will be provided. Instead, the film charts a more existential path as it follows this group of men into unknown territory, where their sense of duty will be tested both morally and spiritually—matters that slowly come to dominate the majority of the conversations, which are otherwise concerned with the mundane and the prosaic. Indeed, few war films have ever been less focused on the machinations of warfare, let alone combat. There’s only one battle sequence in The Damned, and the fighting is depicted almost impressionistically, in a succession of long takes that track individual members of the troupe as they flee gunfire from an unseen enemy.

Shot largely at dusk by cinematographer Carlos Alfonso Corral, the film is burnished in a kind of muted glow, lending an appropriately elegiac air to a narrative centered on questions of faith and mortality. As in Minervini’s nonfiction work—which has dealt exclusively with various rural communities and subcultures in the American South, where the director lived for almost two decades after moving to the US in 2000 (he’s now based in New York)—these are themes brought forth by his performers (some of whom were featured in Stop the Pounding Heart, 2013), whom he calls on to contribute ideas and character details from their own lives. This collaborative approach reached its apotheosis with The Other Side (2015) and What You Gonna Do When the World's on Fire? (2018), films that fearlessly documented contemporary race relations from opposite ends of the sociopolitical divide. With The Damned, Minervini continues this project by other means, tracing issues of class, oppression, and discrimination to a watershed moment in American history that, period trappings notwithstanding, feels frighteningly current in an era of extreme political polarization.

Shortly after The Damned’s premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, where Minervini picked up the Best Director prize in the Un Certain Regard sidebar (in a tie with Rungano Nyoni, for On Becoming a Guinea Fowl), we met to discuss the film’s contemporary resonances and how his idiosyncratic approach to fiction helped alleviate the weight of written history for both himself and his actors. A year later, the film is making its US theatrical debut.

NOTEBOOK: Can you talk about the impulse to work more directly in fiction with this film? Is this something you had always wanted to do?

ROBERTO MINERVINI: Yeah, I had been wanting to do it for a while. I wanted to step into a territory where I could digress on certain topics, and move freely from past to present, without having to abide by any codes. I wanted to see how it felt, while also keeping to certain aspects of my established approach, which stems from individuals and what they bring to the table and how they influence the writing process. I wanted to apply this in a fictional realm where I could enjoy a different kind of freedom—not necessarily a formal freedom, just because there are dramaturgical codes in fiction, but an ethical freedom, where I could digress as much as I wanted from factual truths.

NOTEBOOK: What was your conception of the Civil War before moving to the US?

MINERVINI: The US Civil War is known globally as the war that put an end to slavery. It’s seen as the quintessential war of Good vs. Evil, with the Union being the good guys. That’s how I learned it, back in Italy. But my interest in this chapter of US history has less to do with me moving to the US than with me moving to the South. I spent fourteen years living in Texas, digging deep into the past and present, studying history and documenting several local communities. My main drive was to come to a more thorough understanding of the reasons for the distrust towards the federal government, which runs very deep in the South. And some of those reasons can be found in the nineteenth century North–South divide.

NOTEBOOK: Did your experience with The Other Side in particular influence your desire or approach to making The Damned?

MINERVINI: In a way, yes. Because for me every film I make is a starting point for further reflections on what to do next, in terms of cinema and subject matter. I look at what I have learned from the experience, see how my language and aesthetics can evolve, and how the experience will inform the next one. So, everything that I experienced and observed when I made The Other Side has inevitably influenced the way I looked at the issue of war, which is central to The Damned. At the same time, I can say that Stop the Pounding Heart also informed The Damned, and the centrality of God in the discourse around war. And What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire? also informed it, because it’s a film about America being at war with itself.

The Damned (Roberto Minervini, 2024).

NOTEBOOK: Why did you decide to focus on Union soldiers in this specific part of the US?

MINERVINI: I had been studying not only the Civil War but also the aftermath—the years immediately after, the American Indian wars. A lot was happening in this territory, which is Dakota territory, and in Montana specifically, where some of the most dramatic battles of the nineteenth century took place. But there were no Civil War battles in Montana. The US Army got involved only to take control of the natural resources during the Gold Rush. I wanted the film to be set in a fringe territory, an inhabited land where the weight of written history was less heavy for the actors—less heavy for all of us, really. Now, imagine I had set the film in Harrisburg or the Valley of Shenandoah: we would have risked getting smashed by the weight of history, we could have become referential, less free in the way we wanted to talk about nineteenth-century America. For me, there’s nothing freeing about abiding by the precepts of written history in cinema. I knew it would be different to make a war film that was highly experiential, where the actors bring their stories into the overall narrative, so I thought if the characters they played were volunteer soldiers, kind of minor players in the grand scheme of the Civil War, it would allow them to be who they are, to bring their own stories, thoughts, and feelings into the film. Sometimes they were confused about what’s going on, or unable to recall clearly the motives behind the war; other times they felt free to bring their own Christianity or atheism into the overall discourse.

NOTEBOOK: You worked with Lisandro Alonso on the US-set section of his film Eureka (2023), which also takes place on Native American land. Did the trips you took for his film influence your decision to shoot in Montana?

MINERVINI: It’s funny because my mind was already set on Montana when I started talking to Lisandro, who was planning on shooting in South Dakota. We talked about our projects and I advised him a little on the territories where he could film. It was nice. Our films sort of inform each other, but from opposite directions. Lisandro was really exploring what the Pine Ridge Reservation meant, which is written in history, and in codes, and in cinema. Whereas I was trying to shy away from all that. Lisandro wanted to be in the middle of things, in the epicenter of some of the most painful chapters of Native American history, so that the people would know where he was in relation to that history—why he should or shouldn’t be there. In my case, things were murkier, because I wanted to create something very experiential, less entangled with historical and factual truths, so I set my film in the remote territories of the Western frontier.

NOTEBOOK: Can you talk about crafting the scenarios with your actors and what they brought to the characters? Was the process much different from your past work?

MINERVINI: I began by talking to all of them, to make sure that going back and exploring that time, and also drawing parallels with the present, was something they were comfortable doing. At that point I didn’t have a story in mind. It was brewing in me, but I didn’t share it with them. All I told them was that this film would be about war existentially—the condition of being in war. I said that since I’m not looking for a way out of this existential condition, let’s bring it down to something very essential, which is the battle. A battle has a before and an after. It’s a way of seeing and dissecting the experience of war that stems from literature: The Aftermath of War [by Jean-Paul Sartre], for example. So, I thought, let’s go back to something very simple, and we’ll build the story around the battle, with a before and an after. Let’s see how that plays out. We know the “before”: There’s a journey, which you can only predict to a certain point. After the battle, let’s reassess the situation: Where should we go? What should we do? Just rot and die? And so, we built on this idea: a journey, an assessment, questioning the motives, and then seeking solace in the fact that they’re alive, and that perhaps there’s a way out.

These two parts, the before and after, end up mirroring each other, but they feel different because the battle echoes across the second part. That’s how I presented the shoot to them. They came with their own ideas and knowledge of history—contemporary history and Civil War history—and that knowledge reflected the reality of how they’re different from one another.

The Damned (Roberto Minervini, 2024).

NOTEBOOK: How did you build out and shape the film from this central battle sequence? Did you shoot a lot of footage?

MINERVINI: The final shape of the film is very faithful to the initial idea. I didn’t shoot a whole lot of footage. Or perhaps I did compared to the standards of conventional filmmaking, but I didn’t shoot the massive amount that I normally do. Once you take people out of their element and place them somewhere new, where they’re forced to be idle at times, while getting acquainted with each other and the surroundings—that shrinks down the amount of footage I need to shoot. Even for the battle we didn’t shoot a lot, but we did shoot every day for probably fifteen to twenty days, mainly following each individual going down a path as day turns to night—usually until it was pitch black. Some of that pitch-black footage was used, and some of it couldn’t be used. And then we filmed the people shooting from far away. Going through the whole experience was actually very jarring. To be alone in a land we don’t really know, inhabiting a space of war, and to do that over and over with each character was scary.

NOTEBOOK: Can you talk about the idea of depicting an unseen enemy?

MINERVINI: As soon as an enemy is identified as such—there are tropes of cinema, and of written history. When that happens, you form an attachment. “Am I taking sides with the good people?” There’s something very perverted, sickening, even poisonous about that, in the context of war. Humanity kicks in and all of a sudden, you’re rooting for someone to be smoked out, or eradicated. The phrase “smoke them out” is something I remember from the [George W.] Bush presidency. War is politicized to the point that we become desensitized about the human beings who fight it, and die in it—so we stop caring about the “bad guys,” human beings on the other side, suffering and dying. I wanted there to be no identification of evil, so therefore there’s no identification of good, per se. Plus, we see the silhouettes of the shooters, wearing specific cowboy hats and holding rifles upright, which recall the iconography of Old West movies. So, in conceptual terms, the enemy in my film is just a signifier, an interpolation of every enemy representation, of every battle, in every sort of war cinema—not just Old West cinema. There’s something enticing about that 360-degree tradition of war cinema, especially in American cinema, where the depiction of an enemy as a recognizable, unequivocally evil entity served one main purpose: to spread the idea of “good cause” that justifies a war action.

NOTEBOOK: Regarding the parallels between past and present, were the anachronisms in speech and behavior something you wanted to emphasize, or was that something that the actors brought forth in the moment?

MINERVINI: I left it up to them. But I knew, based on the casting, that these sorts of things would likely occur. I knew how certain people talked. Some of them are California dudes—the word “dude” is in the film! [Laughs.] I ultimately felt it was constrictive to try and contain language. When you look at the footage you can see when they’re so into the conversation that the language becomes today’s language. I’ve talked about this a lot as it relates to my other films, but I know that performers sometimes need to keep their guard up—the performance of the self is something very vulnerable. Everyone has their own devices, and sometimes they want to act, and sometimes they want to be disruptive. I need to respect their fragility. For me that transcends the representation of history, and reenactment. It’s about allowing them to perform from within, as well as letting them choose the words, or silences, to express themselves.

The Damned (Roberto Minervini, 2024).

NOTEBOOK: How did the religious and spiritual aspects of the film become so prominent?

MINERVINI: I think it stems from the political debate between the performers. For some of them, like the young guy from Stop the Pounding Heart, political and ideological matters have to be brought back to a higher discourse, which is the spiritual or the religious. So, there’s a constant dialectic between the spiritual-religious and the political-ideological. That scene where they discuss spirituality—they talked from day to night. And then they asked me if they could do it again, because they weren’t done—especially the young boy. He couldn't believe that some of the other actors were reducing the issue of “dying in war” into something petty, human, as if you have control of it all, as if there isn’t a higher power that gives a meaning to war. He was frustrated, but he couldn’t let go of it. So, the shift from the spiritual to the political discourse is quick. And we can legislate over it. Think about today, when they say, “Hey, there’s a supreme law here in the United States. It’s the Bible.” That idea is something closely linked with the movements that are arising now.

NOTEBOOK: Your production company, Pulpa Film, has produced two films so far: Eureka and All We Imagine As Light, which also premiered at Cannes. What made you want to work with Lisandro Alonso and Payal Kapadia?

MINERVINI: Lisandro and Payal are people that I’ve gotten to know well throughout the years. I appreciate how independent and idiosyncratic they are, and I admire how protective they are of their methods. I like to be of service to their vision—not to be hand-in-hand necessarily, but to step back and be there when they need something. “You lead, I follow,” is the basic understanding. And then when we’re there I might ask why they made a certain choice, and if they want to consider a different way, even if it might be scary. With Lisandro, things were really alive. It was fertile ground for us to talk. With Payal, I wasn’t there on the shoot, but I was there from the beginning of the project and we were able to draw parallels between our approaches. It was a beautiful process.

![[FREE EBOOKS] Modern Generative AI with ChatGPT and OpenAI Models, Offensive Security Using Python & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

.webp?#)