In Wisconsin, How Has A Rural Respite for Learning Become a Statewide Haven for Healing?

Norris School District in Wisconsin creates a unique learner-centered environment, empowering youth through personalized learning and community integration. The post In Wisconsin, How Has A Rural Respite for Learning Become a Statewide Haven for Healing? appeared first on Getting Smart.

The landscape of Southeast Wisconsin feels like it belongs to another era.

Wavy prairies and sentinel rows of Maple and Oak trees fill its ample spaces, providing a sense of solitude amid modernity’s encroachment. The entire region is situated on geologic formations that are more than 20,000 years old, covering the ground with pockmarked depressions, or “kettles,” that were formed by the melting of buried blocks of ice some long-ago glacier left behind. And if you’re here in late winter, a ubiquitous sepia, like faded monochrome, blankets the groundcover until Spring’s vibrant color palette starts to seep back into the frame.

For Daniel “Niel” Norris, it was love at first sight.

The grandson of Wisconsin’s richest man, Norris spent his summers here more than a century ago, blissfully removed from the frantic pace of his Milwaukee home. Yet one afternoon in 1911, the landscape took on a different role: it became the central setting for his life’s work.

Day after day, he’d park his Model T outside the family factory—only to return and find his headlight bulbs missing for the drive home. So Norris lay in wait to apprehend the thieves: a pair of young boys, it turns out, who’d been amassing pilfered lamps and batteries in a pigeon coop so they could tinker with electricity.

Inspired by their ingenuity—and their need—he organized a summer camp in Mukwonago, and more than fifty boys showed up.

Then it ended, and a majority of them confessed that they had nowhere else to go.

So Niel Norris decided to create a home base for the homeless. He bought a neighboring farm, and then another. He built a schoolhouse, and then a gymnasium. He hired teachers and houseparents, blacksmiths and herdsmen, mechanics and managers. And gradually his vision grew to the point that it covered nearly 900 acres of these open prairies, becoming its own singular school district—the state’s smallest—and identifying this corner of southeast Wisconsin as the home of the “Norris boys.”

Over the years, however, a different reputation took root. “I grew up in this area,” said Amber Ehrmann, who has worked as Norris since 2020 “so I remember when this community had a lot of misperceptions about the Norris boys. And Mukwonago is a big city around here, so it can be hard to change the entrenched perceptions that people have about things.

“But when I look at what our staff has done, we really have changed that perception,” Ehrmann boasted. “And now, when people talk about our learners, it’s about what they’re giving the community, not what they’re taking from it.”

Today, Norris School District has more than thirty adult mentors, supporting the needs of about seventy adolescent learners.

The numbers are always changing, however, because Norris’s population is highly transient. Many of its students are adjudicated youth who have been assigned to a nearby residential treatment center. Consequently, some will be at Norris for as little as a month, whereas others may stay for years.

“But all of them,” explained Kris Koneazny, Norris’ Director of Learning, “have experienced deep trauma in their lives. Most have experienced a fair amount of institutional trauma as well. So usually, when our kids arrive, they are pissed off.“

That sort of environment requires a certain type of adult—and a different sort of job profile than a typical educator position. But for Norris’s staff members, that’s what makes the work feel so important.

“After coming from a conventional school, the way we approach relationships here feels like a revelation,” explained Ehrmann. “Those places are designed to treat all learners the same. But they’re all different. So if a learner is dysregulated or struggling, it’s my job to discern what else is going on behind the scenes, and try and help them both identify and then address that unmet need.”

For executive director Johnna Noll, the purpose of a place like Norris is “to help learners figure out what their next best place can be when they leave us. This is year 36 for me in education,” she told me, “and this is the best team I’ve ever had. We really meet learners where they are, and support each other in what can be difficult work. Most of our kids have experienced failure, repeatedly. But we welcome everyone here. And we celebrate even the ittiest-bittiest progress they make. And we all share a commitment to change lives through the power of learning.”

The way Norris does that is by crafting an environment that is relentlessly learner-centered. It begins upon arrival, through an orientation process in which each young person is asked to reflect on who they are, what they care about, and who they want to become.

As Koneazny put it, “our main goal is not to teach them how to turn in an assignment on time; it’s to teach them to reflect deeply on who they are and what they want and need.”

To help them get there, Koneazny collects “urgency stories,” intimate conversations between the learners, their families, and the school. “It’s our first insight into who this person is and might yet become,” he said. “But we’ve also learned how important it is that we not bombard them. They need space to decompress. You have to know that it could take upwards of a month or more to unlock the conversation with a learner that you really need to have. But that is more important than anything else we do.”

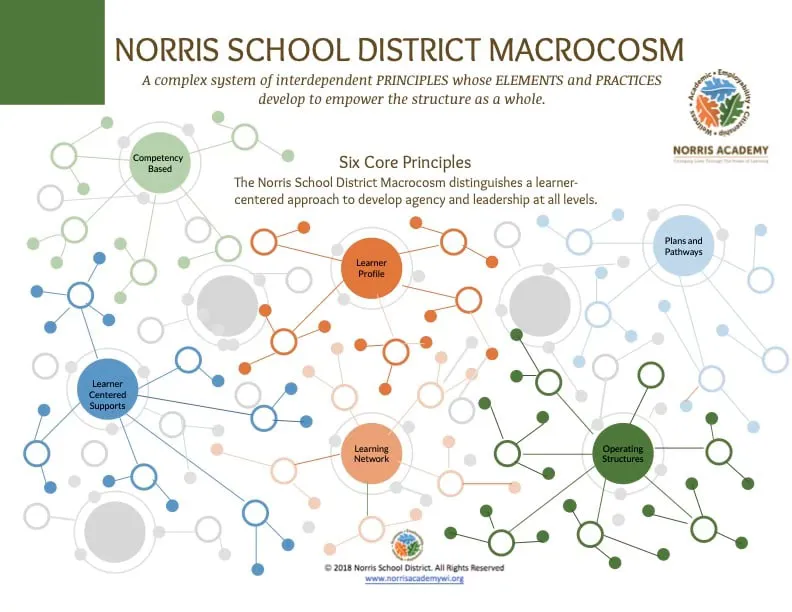

To facilitate such slow and steady work, a learner’s day at Norris is intentionally designed to give each child time and space to direct their own learning. Its overarching structure is called the Norris Macrocosm, which Noll describes as “a complex system of interdependent principles whose elements and practices help empower the structure as a whole.”

“Every learner has their own learner profile here,” she continued. “Every learner gets to co-design their own personalized plan and pathway. All learning is competency-based. All adults are here to provide different forms of support, from academic to social/emotional. And everything we do is designed to help each learner figure out how and what they like to learn.”

In addition, Norris is seeking to provide an increasing array of community-based learning opportunities—which means directly confronting the timeworn assumptions about what a Norris student is—and is not.

A few years ago, it opened a virtual school so that learners from other communities could stay connected even after their tenure on campus ended. This winter, it launched two satellite campuses in a pair of Milwaukee-based non-profits. And this school year, it joined the inaugural cohort of twelve communities across the country that are working with Education Reimagined to establish true “learner-centered ecosystems” — ones that effectively weave together a diverse network of field sites, learning hubs, and home bases that can help young people thrive.

“The work to establish these Learning Hubs is brand new,” Noll explained, “but we’re trying to become even more community-based in our network. We want to partner with other residential treatment centers and non-profits serving disadvantaged youth across the state. And we’re planning to set up a professional development program so we can help prepare adults to support young people in recovery.”

Under Ehrmann’s leadership, in fact, Norris is actively recruiting a wide range of civic partners to provide internships that will help learners explore the interests they identify in their urgency stories. And although many of these partners are based in Mukwonago, the school’s network now extends all the way to Milwaukee, where a number of its students are located.

“What we’ve seen already,” Ehrmann explained, “is that in the places that have welcomed our learners in, they’ve gained as much from it as the learners have. And even though we have all this acreage and all this natural beauty to call on, we want to make sure that our learners get to spend a lot of their time in true community settings. Our goal is to establish a statewide haven for healing—and a learner-centered ecosystem in which young people who have fallen through the cracks of their communities finally start to get the attention they deserve.”

For J., an adjudicated teen from Milwaukee who has been at Norris less than two months, that sort of attention has already been life-changing. “I never knew what I wanted to be until I got here,” he told me. “How shall I say this? At my former school, nobody asked me anything. I was expected to just sit all day and have security guards tell me what to do. But here, we can work on all sorts of things. And everyone is always encouraging you to try something new.”

J. is long and lithe, with cornrows that hug the crown of his scalp, and a sweet tendency to smile when he speaks. It’s hard to imagine him doing anything that would require the intervention of the law. But that’s the impact of the Norris team, whose sole focus is building young people back up after a lifetime of feeling ignored. And already, just two months in, the light within J. is pouring out.

“We’re trying to change his mindset of what education is,” Koneazny told me later. “And the reality is we have no idea how long we’ll have him. But now that we’ve opened the Milwaukee Learning Hubs, we have another way for a learner like him to stay connected.”

By contrast, eleven-year-old K. is here by choice, and has been for three years. I watch him patrol the halls for hours, driven by a dark energy he cannot name. At one point he kicks the glass of a door so hard it feels like it might break. Yet throughout the day, another of Norris’s staff members, Matt Bornheimer, walks alongside him, a mobile therapist of sorts, offering whatever ballast K. might be willing to accept.

“Like a lot of our kids,” Matt tells me, “the ones that need the most love seek it out in the most unloving ways. But every day here promises a different breakthrough—or breakdown. There’s just so much trauma being worked through. But our job is to model respect, not to insist on it for ourselves.”

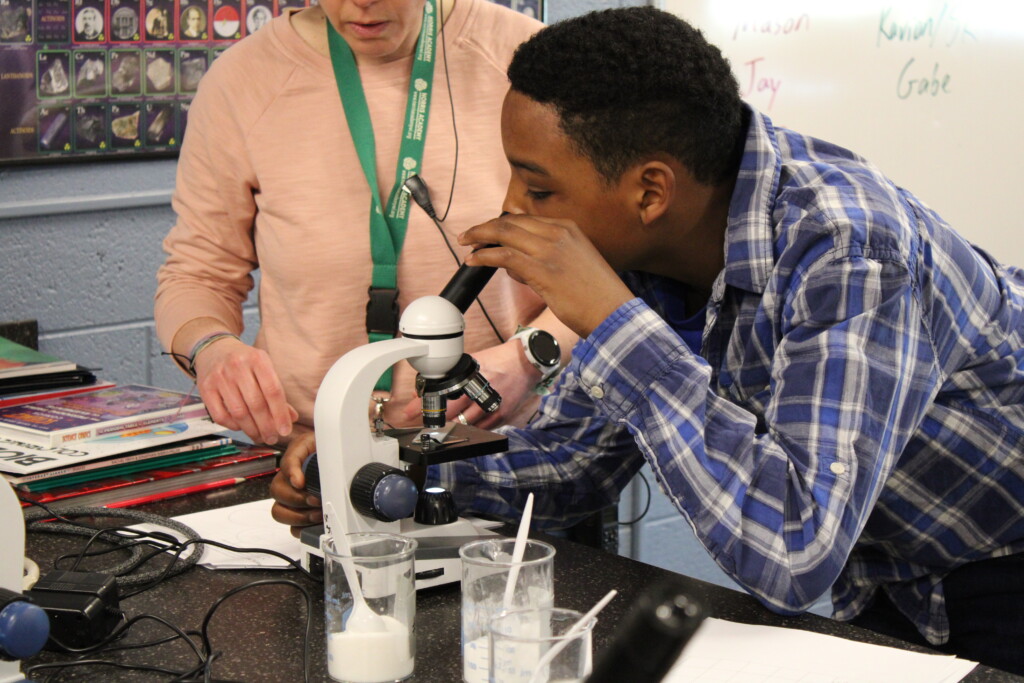

While Matt keeps pace with K., a group of older kids shoot baskets in the gym with Jazz Peavy, another one of Norris’s “Learning Navigators.” In a different room, one young learner is transfixed by a set of sugar crystals that Norris’s Science Specialist, Ryan Thompson, has placed under a microscope. And everywhere throughout the building, adults watch and wait, reading the needs of their charges, and deciding from moment to moment what will get each child to their next best place.

Later that afternoon, Ryan and two pre-teen boys head out for a community-based experience to a nearby pet store. “For a lot of our kids,” Thompson tells me, “the most important thing they can learn is how to care for another living thing. Two years ago, we built the chicken coop. Last year, we added the fish tank. And now, it’s the snake.”

A baby corn snake, to be precise—no longer than a dinner knife. “We need to get her this week’s meal so she doesn’t go hungry,” Thompson explains to the kids. “But we’ll get to see a lot of other animals while we’re there.”

It’s true—the pet store is awash in cool creatures, from tarantulas to scorpions, and geckos to birds. One boy proceeds warily, but the other presses his face right up to the edge of their glass containers. When the owner hands Ryan the frozen pinky mouse, he volunteers to hold it during the ride home.

The bag rests on his leg as we rumble our way back across town—past sepia prairies, sentinel trees and grain silos.

“I like it here,” he says out loud to no one in particular. “I’m never leaving. It’s my favorite place in the world.”

This article is part of a series highlighting sites from Education Reimagined’s Learner-Centered Ecosystem Lab. In collaboration with writer, filmmaker, and global design consultant Sam Chaltain, Education Reimagined is showcasing the development of learner-centered ecosystems in communities across the United States.

The post In Wisconsin, How Has A Rural Respite for Learning Become a Statewide Haven for Healing? appeared first on Getting Smart.