Pope Leo XIV’s recent predecessors at the Vatican defended migrants. Will he do the same?

Pope Francis, as well as all the pontiffs who preceded him since 1939, defended migrants and immigration. What stance will Pope Leo XIV take?

Political language is sometimes used to describe the orientations of the Vatican. When the late Pope Francis defended migrants, it was suggested that he was a “left-wing” pope. Today, people are wondering whether Pope Leo XIV will adopt a “progressive” path or, on the contrary, a philosophy on immigration different from that of Francis.

To answer this question, it is helpful to look at what successive popes have said about welcoming foreigners. We can see that they have defended not only migrants but also a right of immigration. Their approach has been universalist and it rejected all discrimination. Could it change?

Supporting the right of immigration

During the period between the second world war and the election of Leo XIV, the Vatican had six popes. The first, Pius XII (1939-1958), seems to have been more in favour of immigration than the United Nations. In 1948, when the UN adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, emigration was enshrined as a fundamental right: “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own.”

This wording does not mention the right to enter a country that is not one’s own, and Pius XII called this vagueness into question. In his 1952 Christmas message, he argued that it resulted in a situation in which “the natural right of every person not to be prevented from emigrating or immigrating is practically annulled, under the pretext of a falsely understood common good”.

Pius XII believed that immigration was a natural right, but linked it to poverty. He therefore asked governments to facilitate the migration of workers and their families to “regions where they could more easily find the food they needed”. He deplored the “mechanisation of minds” and called for a softening “in politics and economics, of the rigidity of the old framework of geographical boundaries”.

In the Apostolic Constitution on the Exiled Family, also in 1952, he wrote about why migration was essential for the Church.

Pope John XXIII (1958-1963) extended this argument in two encyclicals: Mater et magistra in 1961 and Pacem in terris in 1963. Whereas Pius XII had thought that the natural right to emigrate only applied to people in need, John XXIII included everyone: “among man’s personal rights we must include his right to enter a country in which he hopes to be able to provide more fittingly for himself and his dependents” (Pacem in terris 106).

A refusal of discrimination

For Paul VI (1963-1978), the Christian duty to serve migrant workers must be fulfilled without discrimination. In a 1965 encyclical, he maintained that “a special obligation binds us to make ourselves the neighbour of every person without exception and of actively helping him when he comes across our path, whether he be an old person abandoned by all, a foreign labourer unjustly looked down upon, a refugee… ” He also stated the requirement “to assist migrants and their families” (Gaudium et spes).

John Paul II (1978-2005) made numerous statements in favour of immigration. For example, his speech for World Migration Day in 1995 was devoted to undocumented migrants. He wrote: “The Church considers the problem of illegal migrants from the standpoint of Christ, who died to gather together the dispersed children of God (cf Jn 11:52), to rehabilitate the marginalized and to bring close those who are distant, in order to integrate all within a communion that is not based on ethnic, cultural or social membership.”

Benedict XVI (2005-2013) acknowledged the “feminization of migration” and the fact that"female emigration tends to become more and more autonomous. Women cross the border of their homeland alone in search of work in another country.“ (Message, 2006)

Welcoming the entry into force of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, he recalled: "The Church encourages the ratification of the international legal instruments that aim to defend the rights of migrants, refugees and their families” (Message 2007).

Pope Francis (2013-2025) embraced this globally inclusive tradition. His encyclical on “Fraternity and Social Friendship” calls for “recognizing that all people are our brothers and sisters, and seeking forms of social friendship that include everyone” (Fratelli tutti, 2020).

He insisted that “for a healthy relationship between love of one’s native land and a sound sense of belonging to our larger human family, it is helpful to keep in mind that global society is not the sum total of different countries, but rather the communion that exists among them” (Fratelli tutti, 2020).

On the question of migration, Francis maintained that “our response to the arrival of migrating persons can be summarized by four words: welcome, protect, promote and integrate” (Fratelli tutti, 2020).

Not a political preference

It appears that the pontificate of Leo XIV will reflect a similar commitment. However, this cannot be explained by political preference, or by personal and family history (the US-born pope is the grandson of immigrants and became a naturalized citizen of Peru). Popes do not defend immigrants because they are left-wing or progressive, but because they are at the head of an institution whose raison d’être is “to act in continuity with the mission of Christ”.

For Christians, welcoming foreigners is meant to be a fundamental duty, a condition of salvation. In the gospel, Matthew has Jesus say that this is one of the criteria for the Last Judgement. Those who welcome the stranger will receive the kingdom of God “as an inheritance”. Others will receive eternal punishment: “For I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty, and you gave me no drink, I was a stranger, and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not clothe me, sick and in prison and you did not visit me” (Matthew, 25:42-43).

The stranger is at the heart of the New Testament revolution. Of course, the imperatives of hospitality are found in both the Old and New Testaments. It is a hospitality that is demanding (“You shall treat the stranger who sojourns with you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt” [Leviticus 19:34]) and unconditional (“Show hospitality without complaining” [Peter 4:9]).

But the New Testament revolution endows Christianity with a universal aspiration: human beings, by virtue of their origin, all become brothers. Belonging to Christianity itself is reflected by faith in this universality: “We know that we love the children of God when we love God” [John 5:2]. With this message, Christianity blurs the distinction between strangers and relatives: “You are no longer strangers and foreigners, but fellow citizens with the saints and members of God’s household” [Ephesians 2:19].

According to the Letter to Diognetus, this is what makes Christians unique: “They reside each in his own country, but as dwelling strangers. Every foreign land is a homeland to them, and every homeland is a foreign land to them.”

In his very first homily, Leo XIV suggested that the Christian faith might seem “absurd, reserved for the weak or the less intelligent”. But the institution of which he declared himself a “faithful administrator” has been preaching “universal mercy” for over 2,000 years.![]()

Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.

/2025/05/09/000-34rp49b-bonne-version-681dc1312dfca766407434.jpg?#)

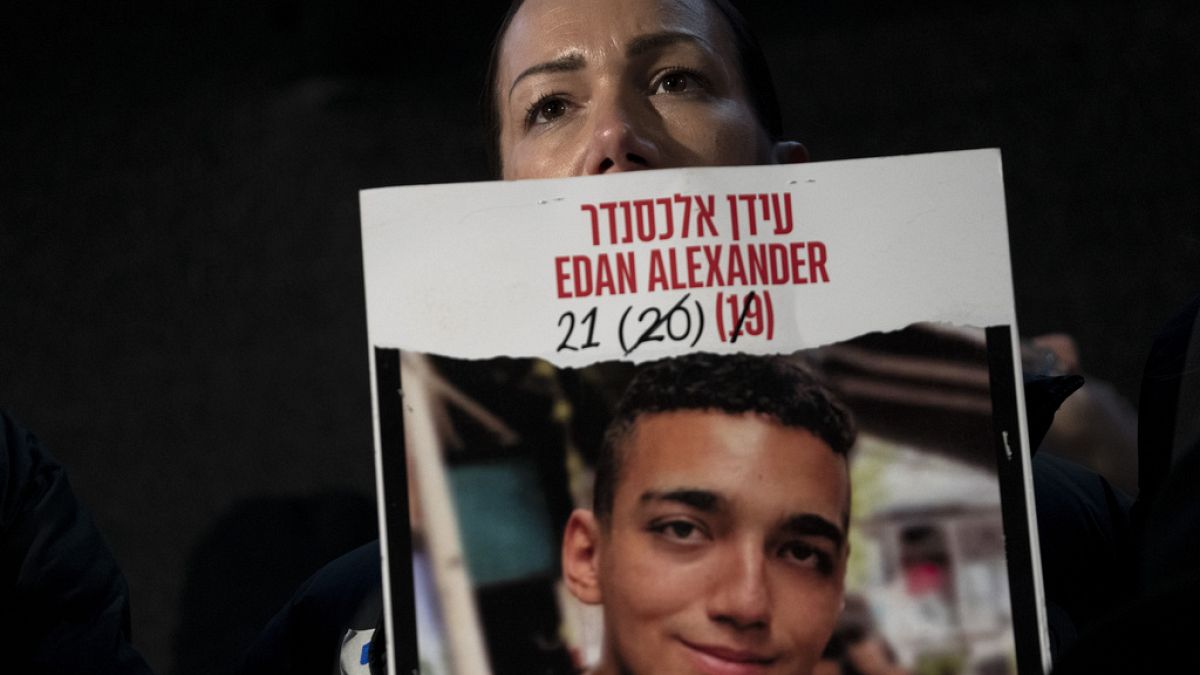

/2025/05/12/000-par1886446-1-6821a58b2655a760562013.jpg?#)

/2025/04/18/gettyimages-987365304-68023070480da056317829.jpg?#)