Cannes Review: I Only Rest in the Storm Glides Over Many Ideas Without Fully Reckoning With Their Weight

Late into I Only Rest in the Storm, Sergio (Sérgio Coragem) is asked a question he can’t seem to answer: what do you care about? A Portuguese environmental engineer hired to evaluate the ecological impact of a massive road set to slice through Guinea Bissau, the man has spent his sojourn in a kind of […] The post Cannes Review: I Only Rest in the Storm Glides Over Many Ideas Without Fully Reckoning With Their Weight first appeared on The Film Stage.

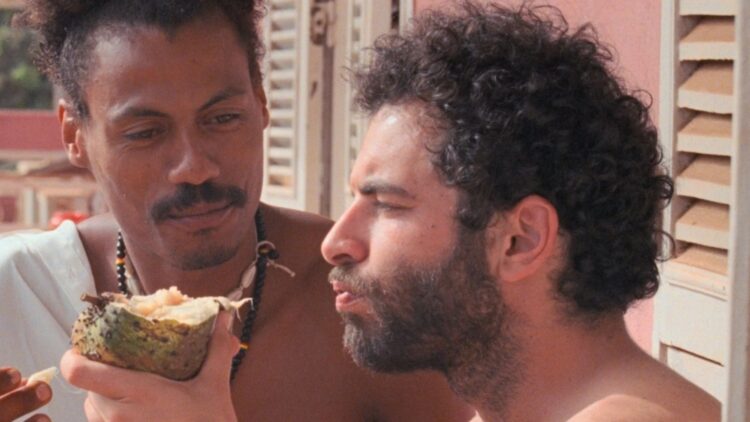

Late into I Only Rest in the Storm, Sergio (Sérgio Coragem) is asked a question he can’t seem to answer: what do you care about? A Portuguese environmental engineer hired to evaluate the ecological impact of a massive road set to slice through Guinea Bissau, the man has spent his sojourn in a kind of existential paralysis. Granted, the gig has sent him traveling far and wide, shuttling from the capital’s luscious villas to hamlets the project will likely wipe out. He’s schmoozed with the local elite, inspected latrines in the country’s interior, and spent days with fellow Portuguese workers stranded in the desert, guarding cranes as tall as cathedrals. But for all this meandering, Sergio’s at a standstill, unable (or unwilling) to come to terms with the role he’s meant to play in a place he’s never seen before and whose future he’s been summoned to decide. “Sooner or later,” a character mused in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, “one has to take a stance, if one is to remain human.” It’s a line that hangs over I Only Rest in the Storm like an ancient prophecy. If there’s any through line to this sprawling, overstuffed film, it’s the denial to which its protagonist has succumbed. Too bad, then, that Sergio should remain a cipher, and that Pinho’s new feature should glide over thought-provoking ideas without quite harnessing their full weight.

It’s a charge that could also be leveled against Pinho’s The Nothing Factory, which turned a strike at a Portuguese lift plant into a coruscating critique of 21st-century capitalism. Described by one of its characters as a “neorealist musical” (even as the musical number only appeared at the tail end), Pinho’s first foray into fiction welded social commentary in the vein of Ken Loach, while fourth-wall ruptures suggested a completely different, almost antithetical register. I Only Rest in the Storm seems cut from the same cloth, which is to say the two are both overlong (The Nothing Factory was just shy of three hours; this one is 30 minutes longer) and happy to get lost in rivulets of ideas. Sergio’s trip to Guinea Bissau gradually starts to splinter; what kicks off as a single man’s A-to-B journey becomes a more and sinuous choral portrait of the milieu he roams, so much so that pegging the white stranger as the film’s protagonist feels somewhat inaccurate. Sergio’s meanderings intersect those of a few folks he brushes past, among them Brazilian crossdresser Gui (Jonathan Guilherme) and Gui’s best friend Diara (Cleo Diára), a young Guinean woman for whom Sergio, predictably, falls head over heels.

But where The Nothing Factory seemed designed to subvert its observational, documentary-adjacent approach––routinely reminding you that what you were watching was a closer to a stage play than kitchen-sink realism––Pinho’s latest strives for something markedly different. Shot by Ivo Lopes Araújo and edited by Rita M. Pestana, Akerman Karen, and Cláudia Rita Oliveira, the film traffics in long, largely handheld shots that do not heighten so much as obscure the divide between fact and fiction. It’s a choice that speaks to Pinho’s background as a documentary filmmaker, and should grant his cast ample room to project a free-flowing naturalism. Which it does, if only up to a point. Several scenes do indeed exude a fly-on-the-wall quality, Coragem et al engaging in heated, often alcohol-fueled chats that, at best, suggest improvisation over scripting. All too often, however, it is not their effortlessness one registers but the film’s tendency to dip into speechifying. As time wears on, Sergio’s neutrality comes under attack, both from those who’ll benefit from the new road and those who’ll likely suffer from it. But the criticism raised against this stranger in a strange land seem oddly mute, a take on his savior syndrome that hinges on the same rote talking points.

Which marks a strident contrast with those moments where the film finally reaches some authenticity for which it’s strained. A short trip to the desert suggests a chapter from Dino Buzzati’s The Tartar Steppe: marooned in the proverbial middle of nowhere, away from loved ones they haven’t seen in years, the Portuguese workers with whom Sergio bunks up look like wardens of a barren purgatory, and in the most riveting sequence, an intramural feud makes I Only Rest in the Storm feel worthy of its tempestuous title. Violent masculinity––the way protracted confinement to a foreign land can push men to their breaking point––is only one of the many themes Pinho teases. Environmental collapse, gentrification, and the legacy of Portuguese colonialism across the country: as with The Nothing Factory, I Only Rest in the Storm has a lot on its mind, and like that earlier work, these ideas aren’t synthesized into a cogent whole but left to collide against each other. Yet the resulting mess hits differently this time. That Pinho should leave so many threads hanging in The Nothing Factory felt somewhat fitting for what basically amounted to a takedown of capitalism: it was the film’s middle finger to corporate efficiency. Here, a surplus feels harder to justify.

Is the film’s constant zigzagging meant to echo Sergio’s own restlessness––his inability to truly “be where he is,” as Gui at some point teases him? Or is it instead Pinho’s attempt to do away with more top-down, Western approaches to storytelling, juxtaposing Sergio’s perspective with myriad others? That would be one charitable stab at interpretation. But it would also gloss over the film’s tendency to spell out its concerns. That I Only Rest in the Storm should overflow with ideas is not in itself an indictment; it’s that the film should gradually shed so many of its mysteries and ambiguities.

I Only Rest in the Storm premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

The post Cannes Review: I Only Rest in the Storm Glides Over Many Ideas Without Fully Reckoning With Their Weight first appeared on The Film Stage.