As Texas road deaths rise, state Legislature weighs bill to shield trucking companies

With insurance rates skyrocketing in Texas, members of the state Legislature are debating a potential solution: making it harder for plaintiffs to sue trucking companies. On Wednesday, the Texas House and Senate held simultaneous hearings on Senate Bill 39, which a broad coalition of trucking and delivery companies argue is essential to stem the rise...

With insurance rates skyrocketing in Texas, members of the state Legislature are debating a potential solution: making it harder for plaintiffs to sue trucking companies.

On Wednesday, the Texas House and Senate held simultaneous hearings on Senate Bill 39, which a broad coalition of trucking and delivery companies argue is essential to stem the rise of insurance rates by stopping what supporters call high-dollar “nuclear verdicts.”

“I learned in law school that the point of the justice system is to make the plaintiff whole, not make them rich,” said Eddie Lucio, a former Democratic representative from South Texas advocating for the bill.

Opposing the legislation were Texas trial lawyers and a long line of Texans who had lost family members or suffered grievous injury in accidents on Texas’s increasingly dangerous roads.

Amy Bolding, an author from Boerne, Texas, related how an 18-wheeler driver on his cellphone swerved into the oncoming lane and hit the car carrying her 5-year-old daughter.

Now, she said, the little girl “has significant scarring all over her body. She has experienced immense amounts of pain. She will likely not graduate from high school or be able to have gainful employment or have a normal life.”

“The conduct of the driver that day was dangerous,” Bolding said. “It was reckless and it was also preventable.” She argued that the new legislation would make it harder for victims like her daughter to get the care they needed.

The debate comes amid two intersecting crises: a 15 percent annual rise in car insurance rates in Texas — among the highest in the nation — and a rising number of fatalities on Texas roads, particularly the violent deaths of about three people per day on the roads of the state's oil-producing regions.

It also comes the week after a deadly accident on Interstate 35, when the driver of an 18-wheeler plowed into a line of cars slowed or stopped in an accident zone. Police observed the driver, a contractor carrying a load for Amazon, “swaying and stumbling” after the crash, but he passed a test for drugs and alcohol.

That was a possible sign of fatigue or distracted driving, some experts told CBS Austin — a problem that truckers told The Hill is endemic across an industry that pushes them to work around the clock.

The main issue discussed in the S.B. 39 hearings was whether plaintiffs like the survivors of those killed in the Interstate 35 accident would be able to tell jurors about a company’s alleged negligent hiring or conduct during the period of a trial when the court would determine whether there has been negligence at all, and who is responsible.

Under the legislation, plaintiffs' attorneys would have to prove on the merits that a driver had been negligent in the specific accident before they could introduce evidence of more general negligence on the part of the company.

For example, trial lawyers argued that if S.B. 39 passed, they would not be able to tell jurors that a company had not properly ensured drivers were trained or licensed, kept them off their cellphones or ensured they weren’t being pushed to drive to the point of dangerous fatigue — as oilfield truckers say they often are — until the facts of negligence had been proven.

Proponents of the bill argued that this reform was needed to stop the rise in insurance costs, which they argued was largely driven by insurance settlements — a phenomenon they contended was driving small businesses into bankruptcy.

Lucio, the former Democratic lawmaker, told the state Senate Committee on Transportation that a 2021 bill aimed at shielding companies from lawsuits had failed to stem the rise of insurance costs. Insurance on the Orangetheory franchises he owned kept rising — an experience he argued was common.

“I get calls from small businesses all the time about rising expenses,” Lucio said, as well as “chambers of commerce that say that businesses won’t relocate to their towns because of the cost of insurance.”

But the idea that lawsuits were a major contributor to rising insurance premiums was “a myth,” testified Jack Walker, the head of the Texas Trial Lawyers Association.

“This is actually a fear-based narrative that we have dealt with the last 30 years, that's actually prompted by the insurance lobby, but it's not true, and it's never been true,” Walker said. He pointed to the insurance industry’s $169 billion in profits in 2024 — nearly double what it made in 2023.

“Insurance companies are making massive profits, but insurance premiums are not going down,” Walker said. Rather than lawsuits, he argued, the rise in insurance premiums came from inflation, increasingly severe extreme weather, more complicated vehicles and more crowded roads. “These are the drivers by the data of what's driving insurance rates — not lawsuits.”

Will Moy, a Houston trial lawyer who had spent a quarter-century defending insurance companies in liability cases, testified that the very frame of protecting “mom and pop” trucking companies was deceptive, because “there is no insurance available on the domestic or international insurance market for a mom and pop trucking company.

“It is available for international trucking companies, interstate trucking companies — trucking companies that are in Phoenix, in Florida, in the Midwest.” The bill, he said, “does not help small business — it hurts small business.”

Another attorney, who represented the survivors of two people killed by an intoxicated driver in the Permian Basin, related that the “mom and pop” company that hired the driver “had been a gentleman from a foreign country living in his basement in Chicago who is hiring sight unseen and unvetted drivers who are driving around Texas roads.”

The coalition of interests backing S.B. 39 sought the enactment of similar reforms in the sweeping legislation passed in 2021.

While that legislation created the skeleton of the two-phase trial system — in which a driver's specific negligence must be proven before a jury can hear about a company's — it included an amendment that still allowed plaintiffs to tell jurors in the initial phase about cases where trucking companies had, for example, knowingly hired a driver with past DUIs, ignored known hazards or disrepair in their fleet or neglected to follow federal safety standards.

The 2021 legislation's passage hinged on that amendment, which was brokered by Lucio, the former lawmaker.

But now, as state Sen. Nathan Johnson (D) noted, Lucio and other supporters of that bill were fighting to remove the language in S.B. 39 — a point other committee members took up. “Everyone here now had their interests represented when we struck that deal,” said state Sen. Royce West (D). “And now we want to redo the deal?”

But the 2021 bill’s author, Sen. Brent Hagenbuch (R), argued that the amendment had effectively blocked the legislation's framework from ever being used at trial. “In practice, it was confusing to trial courts and defendants,” he said.

If the amendment were removed, he argued, victims would still get recompense — but a jury wouldn’t be prejudiced by hearing about a company’s past misdeeds while they weighed whether it had committed any in the case before them.

A major dispute between S.B. 39's proponents and opponents was whether the bill would actually block plaintiffs from talking about a company's negligence.

Lee Parsley of the tort reform interest group Texans for Lawsuit Reform, who testified in support of the measure, argued that “if a car crash broke my arm, then it costs $5,000 to fix the arm” and that plaintiffs' lawyers "want you to get more pain and suffering damages under the law than is actually appropriate.”

Excluding information about a company's negligence from the first part of a trial would mean that “the jury hears a whole lot less evidence that it doesn't need to hear because it is not relevant to any decision left in the case,” he contended.

But Craig Eiland of the Texas Trial Lawyers’ Association, who testified in opposition to the bill, argued that the law would force plaintiffs to leave out essential information.

As long as a driver took responsibility for a trucker’s damages, he argued, they would be shielded from revealing whether, say, they had improperly maintained or loaded the truck, or whether the company had erred by giving the driver a job they were not qualified to do.

“The jury would never hear about that,” he said.

“I completely disagree,” Parsley said. “If you load a truck wrong, that comes into evidence” under another part of the state code.

The argument between the two marked the latest phase in a quarter-century-old battle between Texans for Lawsuit Reform and the state's trial lawyers, one that contributed to Texas's emergence as a Republican stronghold.

That fight properly began in 1994, when a woman grievously burned by and requiring reconstructive surgery from the coffee she had ordered at McDonald's won $3 million to compensate for her injuries — and almost as much as a “punitive damage” intended to keep McDonald's from doing it again.

Republican-aligned Texans for Lawsuit Reform was founded as an advocacy group the same year, and over the next two decades was part of a campaign that capped medical punitive damages in Texas — and thereby cut off a principal source of funding to the trial lawyers, who had been key donors to state Democrats.

In Tuesday's hearing, Parsley was making effectively the same argument the organization has for decades: that punitive damages were out of control, and that companies should be responsible only for the direct harms they caused.

Parsley left after his testimony, and his seat was taken by a string of Texans who largely voiced their opposition to the bill, their stories punctuated by tears and personal tragedy as they detailed what, they said, negligent trucking companies had taken from them.

Two sisters from San Antonio, Julie and Lysanda Saulino, spoke about the 18-wheeler driver on his cellphone who had hit their mother, giving her mother permanent brain damage. “Nobody warned us she'd need all this care and taken care of, and that she would change and not know who we are or we need, and it was just because a trucker hit her,” Julie said.

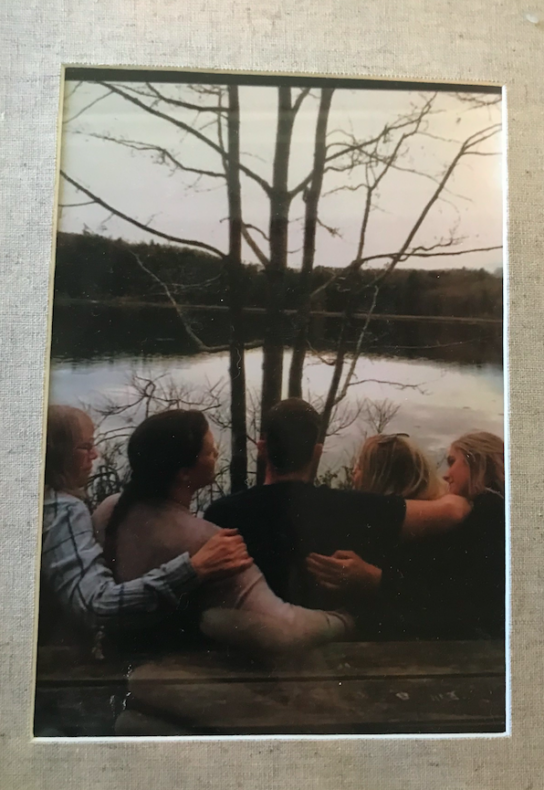

A Houston couple, Jessica and Jason Sprague, testified while holding a framed portrait of their young son, Colton, who died in the hospital after a truck driver ran a stop sign and T-boned their vehicle.

Jason, nodding to the chairs where S.B. 39 advocates Parsley and Lucio had sat, expressed his frustration with “just being here today and listening to the people that were up here and talking about the insurance prices — and then they leave the room whenever the real victims are coming up.”

Their story, Jessica Sprague told the senators, underscored the need for the committee to vote down S.B. 39. Through discovery in the trial after their son’s death, the couple later learned that “while we were trying to save Colton, the truck driver received text messages from his wife about getting urine for his post-accident drug test.”

The driver beat his drug test, and evidence their lawyer uncovered found that “the driver was fired from his last employer before refusing a drug test,” Sprague said. “But the company still hired him because they did not follow the regulations for investigating the driver's background.”

S.B. 39 “would have prevented a jury from knowing why we really lost our son,” she said. “They would have only heard about a man who ran a stop sign.”

![Angela Bassett & Tim Minear Dissect ‘9-1-1’ Shocker, Explain Why [Spoiler] Had To Die, Reveal Alternate Scene & Easter Egg](https://deadline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/911LabEpisode.jpg?#)