Brittany and the Beavers

Ben has had to leave LWON but has kindly left us these memories, these posts which we rerun because we like him so much. Since I published a book about beavers two years ago, I’ve heard from dozens, maybe hundreds, of readers with their own beaver experiences to share. This is a wonderful perk of authorhood: […]

Ben has had to leave LWON but has kindly left us these memories, these posts which we rerun because we like him so much.

Since I published a book about beavers two years ago, I’ve heard from dozens, maybe hundreds, of readers with their own beaver experiences to share. This is a wonderful perk of authorhood: When you tell your own story, you attract others. I’ve gotten emails from folks who have hand-fed blackberries to wild beavers, who have seen beavers build dams entirely of rock, who have watched beavers frolic like seals in the Baltic Sea. Just last month I received the unsolicited memoir of a guy who once resuscitated a drowning beaver. Yes, mouth-to-mouth.

Most writers, I’m sure, get some version of this correspondence. Still, there’s something about beavers — their human-like family structures, their penchant for construction — that seems to foster personal connection. They enter lives in unexpected ways. They channel joy and grief. Today, I want to relate one such saga, courtesy of a woman named Brittany. I’ll warn you that Brittany’s story is about illness and death. It’s also about life and love. And beavers. It’s definitely about beavers.

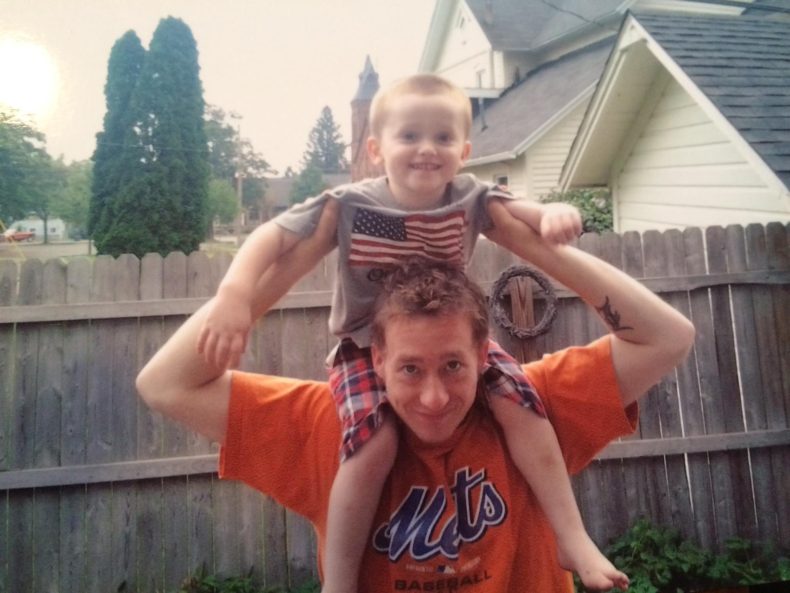

To begin at the beginning: Brittany grew up in Cuba, New York, a small town near Buffalo, the middle of three children. Her younger brother, Zach, was the sort of troubled, likable smartass we all knew in high school — quick with a joke, surrounded by friends, short-fused, prone to starting bar fights. His blend of charisma and anger reminded Brittany of Tony Soprano. “I don’t know if there was a funnier person,” she told me. “He was also a bastard.” He organized riotous backyard wrestling matches and doted on his beagle, Ralphie; he also drank away his money and got arrested the night of Brittany’s bachelorette party. “One time I said something that pissed him off,” she recalled, “and he took a full plate of lasagna and threw it at the Christmas tree.”

In adulthood, the siblings drifted apart. Zach stayed at home, cycled in and out of college, worked at a cheese factory. Brittany, a high achiever, moved to West Virginia to teach at a university. Around 2010, though, she, her husband, and their kids returned to Cuba after receiving terrible news. Zach, at age 24, had been diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive, almost invariably fatal brain cancer. Brittany’s brother was going to die.

The half-dozen years that followed were hard ones. Zach’s health deteriorated; he lost weight, became mentally foggy. Brittany tried to ease his remaining time by hanging a bird-feeder outside his apartment window. Zach spent his days in bed, leafing through a bird guide he could no longer read, watching cardinals and goldfinches flitting through a world he would soon depart.

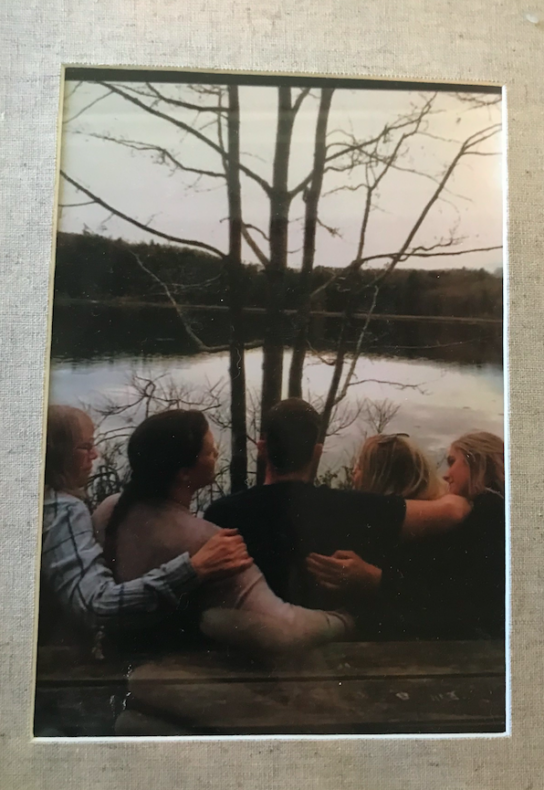

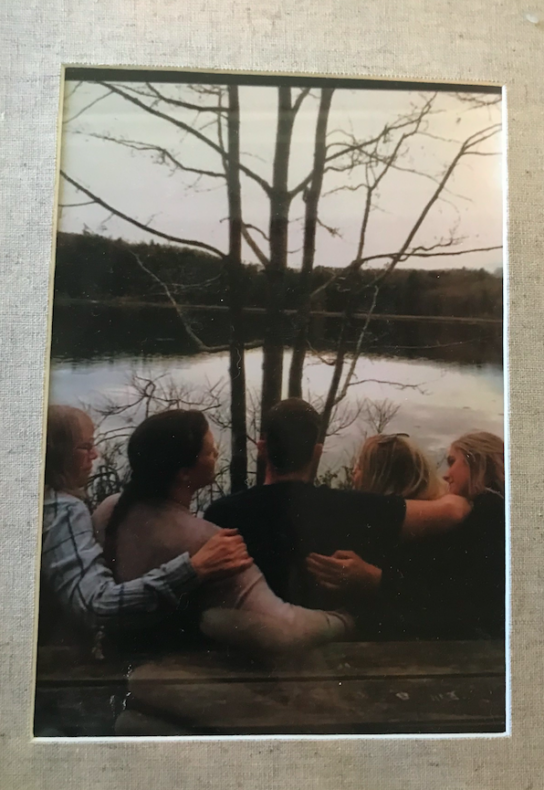

One day in 2016, Brittany, along with her sister, her niece, and her mom, took Zach on a final field trip. A lifelong animal lover, Zach had a special thing for turtles; he even owned a painted turtle, a female named Gary, that their sister brought back once from Myrtle Beach. (It’s still alive today, in the care of their mother). Zach’s dying wish was to visit Moss Lake, a turtle hotspot. “I can remember trying to get him in the car — it was so tragic but so funny,” said Brittany, who has a gift for smiling through pain. “It’s horrible because he’s dying, he can’t move. But at the same time, we’re all laughing because his gut is hanging out, he’s swearing, there’s a cigarette coming out of his mouth, his catheter is falling out of his pocket.” Alas, the turtles weren’t out, but it was still a lovely afternoon. In a photo Brittany sent me from that day, Zach sits flanked by his family, five backs to the camera, their arms twined around each other’s shoulders, the dark timber across the lake reflected in the water’s silver bowl.

Two weeks later, Zach died. Brittany’s family poured his ashes into Moss Lake — illegally, which Zach would have appreciated. The turtles surfaced and ate them all.

***

After Zach passed, his family installed a bench bearing his name (and his beagle’s face) in the Cuba cemetery. Brittany visited often that summer. She only cried once, but she grieved in her own way, talking to her brother and wandering the grounds. The cemetery abutted a sprawling wetland that teemed with geese, ducks, and herons. It seemed like a fitting place to mourn a man who adored turtles.

During one of her vigils soon after Zach died, Brittany spotted a V-shaped wake carving through the swamp. The wake was cast, she realized, by the head of a beaver, the first she’d seen. Brittany, a casual but enthusiastic nature-lover, was thrilled. When she next came to the cemetery, she saw beavers again, and again the time after that. Beavers are ordinarily nocturnal, but this colony was bold and active during the day, perhaps because it had habituated to the cemetery’s foot traffic. Soon Brittany was visiting five days a week, for hours at a time. “I’m at the cemetery trying to feel some peace,” she wrote in her journal one day in July. “And I saw the beavers and Zach would have loved them.”

Peace, at the time, was hard to come by. In the aftermath of Zach’s death, Brittany’s family melted down into chaos and drama; no need to divulge specifics, but suffice to say that, when she compares the situation to Jerry Springer, she may actually be underselling it. The beavers transcended the bullshit. “They were so majestic, so blissfully unaware of the horrors of everything going around,” she recalled. They were, it seemed to her, manifestations of our better natures. They lived in tight family units, like Brittany’s own clan, and they were fiercely devoted to their kits, as Brittany was to her children. But they were also blessedly drama-free, practical, industrious. They did not dread death; they did not betray each other. They were akin to humans, yet superior to them. They also led double lives — sleek and graceful in the water, clumsy and uncomfortable out of it — that seemed to reflect humanity’s own dualism, Zach’s own dualism, how we can at once be so generous and kind and callous and mean, how we all contain multitudes.

Brittany was drinking in those days, maybe a bit too much, and she and her sister would go down to the cemetery with tumblers of gin to talk and sip and watch. Beavers don’t hibernate, and neither did she: When winter arrived, she bundled up and kept going. She’d never been a religious person; after she’d moved back to Cuba, her sister had convinced her to go to church, but her heart wasn’t in it. In beavers, she found her spiritual guides.

“I really started to believe that Zach was in a different place, maybe another realm, whatever you want to call it,” she said. “I never felt that way when I was going to church.” She hesitated, and added, self-consciously, “I know it sounds crazy.”

Spend enough time talking to beaver people, I reassured her, and you hear crazier things.

“I had to see another life force living in a basic, simple way,” she went on. “We’re all living creatures, and humans are no more special than anything else in nature.” There was a kind of comfort in that.

***

Brittany made her pilgrimages to the beavers for two years. And then, one day in mid-2018, they were gone, abruptly and utterly, never to be seen again. Maybe they were wiped out by disease. Maybe they were eaten by coyotes or bears. Brittany suspects they were trapped. That wouldn’t surprise me, either.

A few months later, Brittany’s health began to deteriorate. She felt dizzy and fatigued; she struggled to walk. At the hospital, a wild thought rushed through her aching head: that, although glioblastoma is not hereditary, she had contracted the same disease that felled her brother. She didn’t fear death itself, but she was terrified by the thought of leaving behind her four children. The next day, she received her diagnosis: an aggressive form of multiple sclerosis. Another person might have grieved. Brittany, though, had expected incurable cancer. “I was so relieved,” she said. “I don’t think I even cried once. Like, whatever, I’ll get over it.” She threw herself into exercise and literature; although she occasionally requires a cane, her life has continued mostly unaltered.

The modest scope of her world has in some ways been a comfort. “Once upon a time, I was going to get my PhD, and both my husband and I were going to be college professors, intellectuals,” she said wistfully. They’d dreamt of spending their lives in a quaint college town, or maybe a big city. Instead, they’d returned to Cuba, where she’d become a substitute teacher and run summer sports-and-crafts programs and bumped into high school acquaintances at the only grocery store. First her brother’s disease had narrowed her universe, then her own had constricted it further. Her dreams deferred, she’d found pleasure in quiet, lovely sources: her nature journal, her chickens, the grackle nest on her property. Taking a cue from nature, she had simplified, and she was happy for it.

What’s more, beavers had reentered her orbit. Walking the creek behind her house one day in 2019, she came across a fresh dam and the whittled sticks that are Castor canadensis’s calling cards. Her heart sang. This new colony wasn’t as cooperative as the cemetery beavers, she discovered; she’s only seen one beaver so far. Still, she visits the stream often. “Especially since the quarantine, I find solace in spending time there,” she wrote in her first email to me.

Brittany and I spoke in late May, amidst an unprecedented societal lockdown. All over the country, people were adjusting to smaller, quieter lives, as Brittany had, and escaping their deepening depressions through nature, as Brittany once did. Gardening was ascendant; so was birdwatching. We were all trying to connect with forces deeper and simpler, to commune with creatures blessedly detached from a world that we’d ruined. That, in the end, was what Brittany loved most about beavers: “They’re so unaware,” she said, “of the shit that we go through.”