The Surprising Science Behind Why You're Never Too Full for Dessert

An ode to your "dessert stomach."

We've all been there—stuffed at a restaurant, convinced we can't take another bite, until the server drops the dessert menu. Cows have four stomachs; humans do not. But there is a science-backed reason why we always have a little extra room for dessert, according to new research.

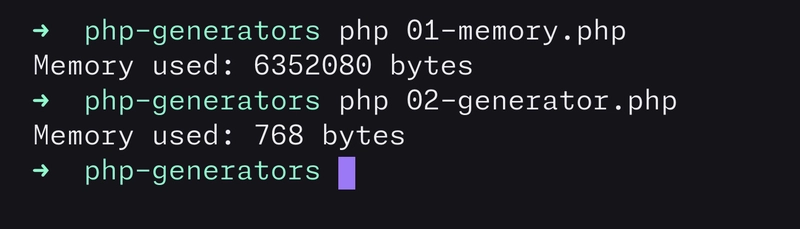

To better understand our "desert stomachs," researchers gathered a group of hungry mice who hadn't eaten the day prior. For 90 minutes, the mice were fed standard chow until they wouldn't eat anymore.

Next, the mice were offered a bit more of the same chow during a dessert period. Although the mice ate a tiny bit more, it wasn't until they were offered a sugary feed that they really gorged themselves. During this final 30-minute period, the mice had six times more calories than they did during the regular chow dessert period.

Scientists believe this is due to pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons being activated by the high-sugar feed.

"We discovered that POMC neurons not only promote satiety in fed conditions, but concomitantly switch on sugar appetite, which drives overconsumption,” the authors said in a statement.

When the mice were originally full of normal chow, the neurons told their bodies they were full.

Related: This Popular Diet May Put You at a Higher Risk for Colorectal Cancer

However, when they tasted sugar, the neurons released beta-endorphins in the mice's brains that triggered their reward systems. So, regardless of the mice being full, their brains told them to continue eating.

“From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense: sugar is rare in nature, but provides quick energy,” said Henning Fenselau, PhD, research group leader. “The brain is programmed to control the intake of sugar whenever it is available.”

Although the study was conducted on mice, previous research suggests that highly addictive ingredients like sugar affect the human brain in a similar way. One study even found that occasional sugar consumption can trigger behavioral and neurochemical changes similar to those seen in substance abuse.

Since sugar releases opioids and dopamine, its addictive potential—and the risk of food addiction—is a real concern.