AI and the Structure of Scientific Revolutions

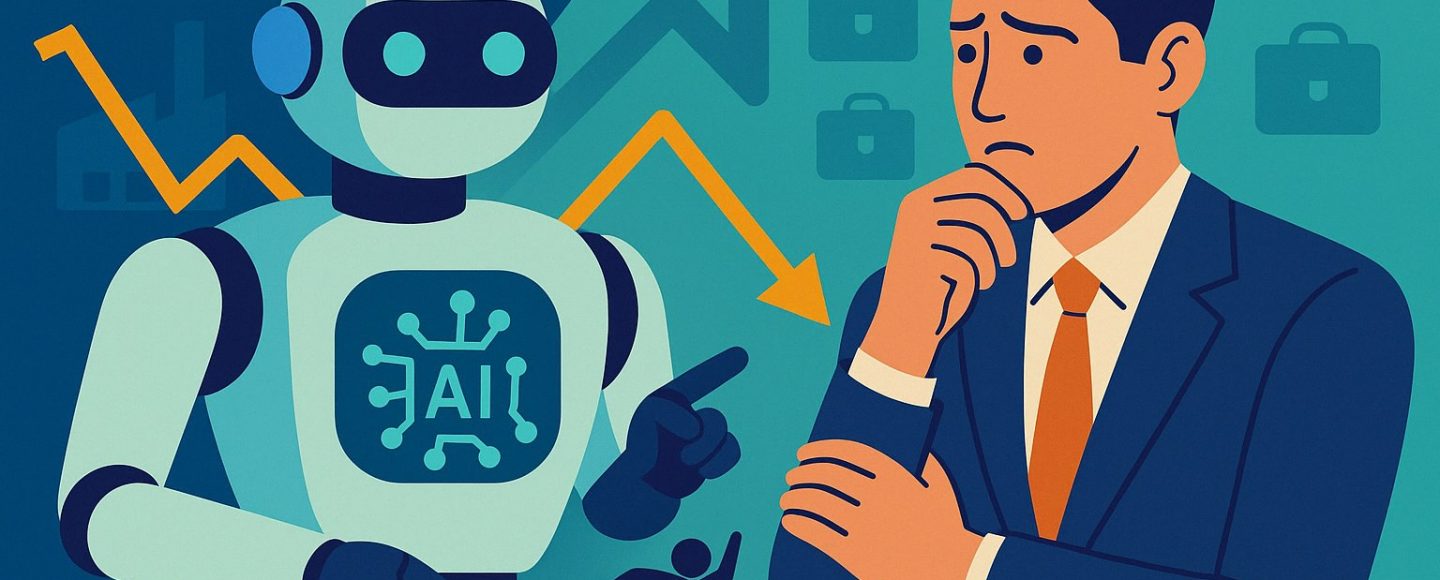

Thomas Wolf’s blog post “The Einstein AI Model” is a must-read. He contrasts his thinking about what we need from AI with another must-read, Dario Amodei’s “Machines of Loving Grace.”1 Wolf’s argument is that our most advanced language models aren’t creating anything new; they’re just combining old ideas, old phrases, old words according to probabilistic […]

Thomas Wolf’s blog post “The Einstein AI Model” is a must-read. He contrasts his thinking about what we need from AI with another must-read, Dario Amodei’s “Machines of Loving Grace.”1 Wolf’s argument is that our most advanced language models aren’t creating anything new; they’re just combining old ideas, old phrases, old words according to probabilistic models. That process isn’t capable of making significant new discoveries; Wolf lists Copernicus’s heliocentric solar system, Einstein’s relativity, and Doudna’s CRISPR as examples of discoveries that go far beyond recombination. No doubt many other discoveries could be included: Kepler’s, Newton’s, and everything that led to quantum mechanics, starting with the solution to the black body problem.

The heart of Wolf’s argument reflects the view of progress Thomas Kuhn observes in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Wolf is describing what happens when the scientific process breaks free of “normal science” (Kuhn’s term) in favor of a new paradigm that is unthinkable to scientists steeped in what went before. How could relativity and quantum theory begin to make sense to scientists grounded in Newtonian mechanics, an intellectual framework that could explain just about everything we knew about the physical world except for the black body problem and the precession of Mercury?

Wolf’s argument is similar to the argument about AI’s potential for creativity in music and other arts. The great composers aren’t just recombining what came before; they’re upending traditions, doing something new that incorporates pieces of what came before in ways that could never have been predicted. The same is true of poets, novelists, and painters: It’s necessary to break with the past, to write something that could not have been written before, to “make it new.”

At the same time, a lot of good science is Kuhn’s “normal science.” Once you have relativity, you have to figure out the implications. You have to do the experiments. And you have to find where you can take the results from papers A and B, mix them, and get result C that’s useful and, in its own way, important. The explosion of creativity that resulted in quantum mechanics (Bohr, Planck, Schrödinger, Dirac, Heisenberg, Feynman, and others) wasn’t just a dozen or so physicists who did revolutionary work. It required thousands who came afterward to tie up the loose ends, fit together the missing pieces, and validate (and extend) the theories. Would we care about Einstein if we didn’t have Eddington’s measurements during the 1919 solar eclipse? Or would relativity have fallen by the wayside, perhaps to be reconceived a dozen or a hundred years later?

The same is true for the arts: There may be only one Beethoven or Mozart or Monk, but there are thousands of musicians who created music that people listened to and enjoyed, and who have since been forgotten because they didn’t do anything revolutionary. Listening to truly revolutionary music 24-7 would be unbearable. At some point, you want something safe; something that isn’t challenging.

We need AI that can do both “normal science” and the science that creates new paradigms. We already have the former, or at least, we’re close. But what might that other kind of AI look like? That’s where it gets challenging—not just because we don’t know how to build it but because that AI might require its own new paradigm. It would behave differently from anything we have now.

Though I’ve been skeptical, I’m starting to believe that, maybe, AI can think that way. I’ve argued that one characteristic—perhaps the most important characteristic—of human intelligence that our current AI can’t emulate is will, volition, the ability to want to do something. AlphaGo can play Go, but it can’t want to play Go. Volition is a characteristic of revolutionary thinking—you have to want to go beyond what’s already known, beyond simple recombination, and follow a train of thought to its most far-reaching consequences.

We may be getting some glimpses of that new AI already. We’ve already seen some strange examples of AI misbehavior that go beyond prompt injection or talking a chatbot into being naughty. Recent studies discuss scheming and alignment faking in which LLMs produce harmful outputs, possibly because of subtle conflicts between different system prompts. Another study showed that reasoning models like OpenAI o1-preview will cheat at chess in order to win2; older models like GPT-4o won’t. Is cheating merely a mistake in the AI’s reasoning or something new? I’ve associated volition with transgressive behavior; could this be a sign of an AI that can want something?

If I’m on the right track, we’ll need to be aware of the risks. For the most part, my thinking on risk has aligned with Andrew Ng, who once said that worrying about killer robots was akin to worrying about overpopulation on Mars. (Ng has since become more worried.) There are real and concrete harms that we need to be thinking about now, not hypothetical risks drawn from science fiction. But an AI that can generate new paradigms brings its own risks, especially if that risk arises from a nascent kind of volition.

That doesn’t mean turning away from the risks and rejecting anything perceived as risky. But it also means understanding and controlling what we’re building. I’m still less concerned about an AI that can tell a human how to create a virus than I am about the human who decides to make that virus in a lab. (Mother Nature has several billion years’ experience building killer viruses. For all the political posturing around COVID, by far the best evidence is that it’s of natural origin.) We need to ask what an AI that cheats at chess might do if asked to resurrect Tesla’s tanking sales.

Wolf is right. While AI that’s merely recombinative will certainly be an aid to science, if we want groundbreaking science we need to go beyond recombination to models that can create new paradigms, along with whatever else that might entail. As Shakespeare wrote, “O brave new world that hath such people in’t.” That’s the world we’re building, and the world we live in.

_Gang_Liu_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_KristofferTripplaar_Alamy_.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)