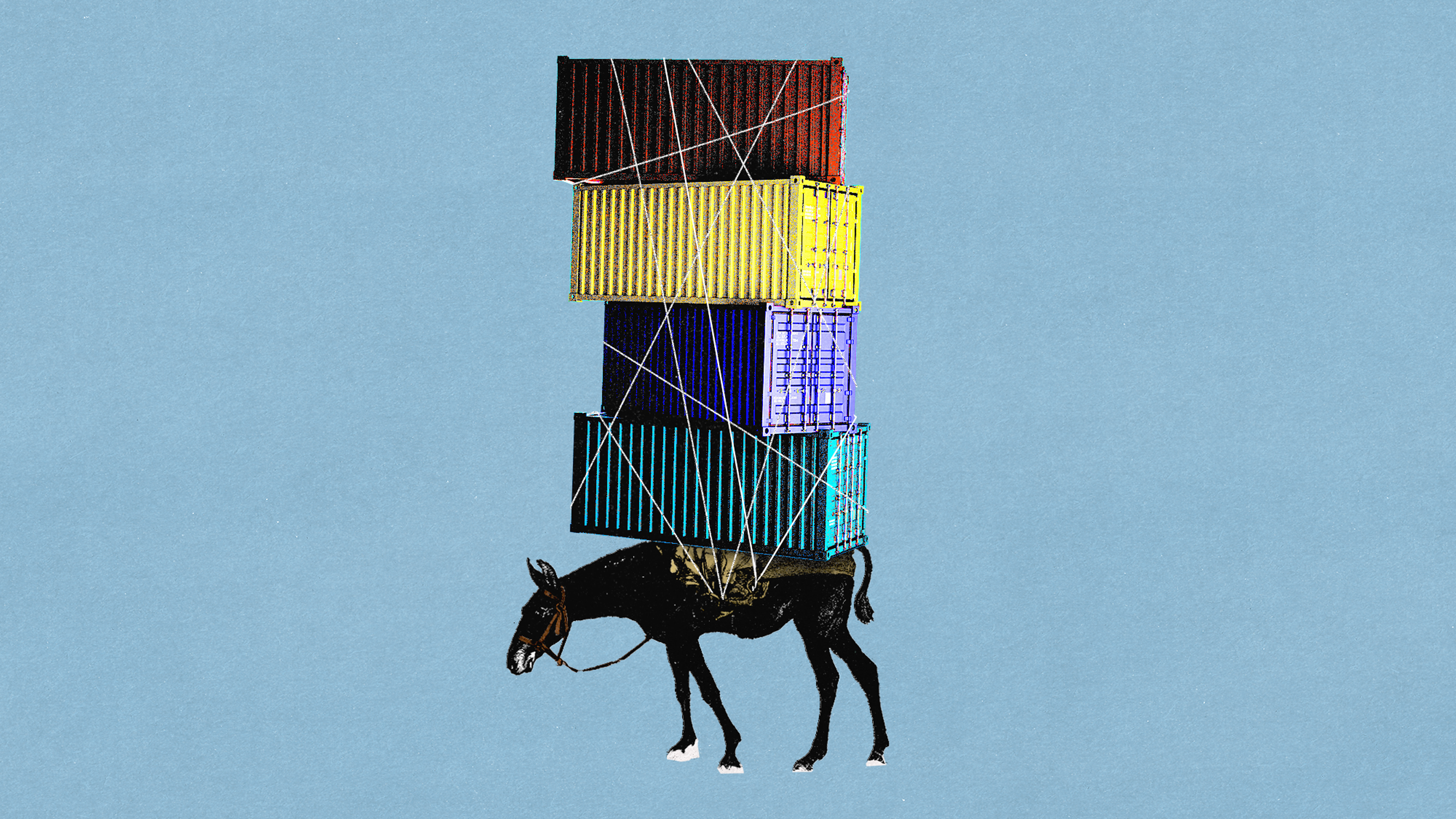

The Impossible Plight of the Pro-Tariff Liberals

They finally got the Democratic Party to listen to them. Then came Trump’s second term.

Lori Wallach was into tariffs before they were cool, and she was still into them when they became uncool again. She cut her teeth fighting alongside labor unions and environmental groups against NAFTA in the 1990s. For more than 30 years, she has been trying to convince Democrats to be more skeptical of free trade. She spent most of that time in the political wilderness, waging one losing battle after another against a powerful bipartisan free-trade consensus. Then the winds began to shift. Donald Trump was elected president after railing against free-trade agreements. Congressional Democrats helped defeat Barack Obama’s signature trade deal, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The Biden administration embraced such taboo ideas as industrial policy and targeted tariffs, with near-universal support from fellow Democrats. The moment that Wallach had been working for her entire career seemed to have finally arrived.

And now she’s watching in horror as Trump sets it all on fire.

Since taking office, Trump has imposed tariffs on Mexico and Canada. He has announced—and then, confusingly, paused—massive “reciprocal” tariffs on the entire world. He has started a full-blown trade war with China and suggested that Americans will simply have to make do with having fewer, more expensive products on store shelves. In the process, he has infuriated America’s allies, paralyzed businesses, sent the stock market reeling, and nearly precipitated a bond-market meltdown. Economists now warn that the economy is headed for 1970s-style stagflation. To ask Wallach where she disagrees with the Trump approach to tariffs is to sign yourself up for a movie-length diatribe. “The last few months have been a master class on how to screw up tariffs,” she told me. “It’s hard to describe just how frustrating it is to watch Trump take what can be a very effective policy tool and completely undermine it.”

[Derek Thompson: There is only one way to make sense of tariffs]

Wallach is not the only liberal trade hawk having a hard time right now. In recent weeks, I’ve spoken with about a dozen politicians, former White House officials, activists, and intellectuals who have helped push Democrats to become more skeptical of free trade. Like Wallach, they fear that the president’s ill-conceived approach to tariffs will discredit the tool entirely in the eyes of voters. Democratic politicians will respond by reembracing free trade. Decades of painstaking progress to build a new trade consensus will be wiped away in a few months. “Trump’s recklessness is playing right into the hands of corporate America,” Sherrod Brown, the former Democratic senator from Ohio, who has long fought for greater trade restrictions, told me. “It has given them an opening to say, ‘Look how terrible tariffs are—we should go back to the old free-trade consensus.’”

These pro-tariff liberals are trying to thread an excruciatingly narrow political needle. They must convince their side that, as bad as Trump’s approach has been, tariffs are still a valuable policy tool when applied rationally to specific countries and sectors. They must do this at a moment when the Democratic base wants nothing more than for its leaders to bring the fight to the current president—a president whose biggest political weakness happens to be tariffs. If they fail, then the decades-long project of building a new trade consensus could turn out to have all been for nothing.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Democrats and Republicans found common ground in their enthusiasm for free trade. NAFTA and the decision to allow China into the World Trade Organization passed with bipartisan support. Plenty of lawmakers, especially Democrats, did object to these deals at the time. But the notion that more free trade was better was so widely held across the two parties that it became part of what was known as the “Washington Consensus.”

For much of his life, Jake Sullivan believed in that consensus. His background reads like the fictionalized archetype of a globalist elite: educated at Yale, then Oxford, then Yale again for law school; winner of the Marshall Scholarship, which he turned down in favor of the Rhodes; intern at the Council on Foreign Relations. As a national security adviser in the Obama administration, he supported the TPP.

The 2016 election shook his faith. Trump ascended to the presidency in part by attacking America’s leaders for shipping jobs overseas and by promising to rip up free-trade agreements. (Indeed, after seeing Trump and Bernie Sanders tap into voters’ resentment toward trade, Sullivan, who at the time served as the top foreign-policy adviser to the Hillary Clinton campaign, encouraged his boss’s decision to denounce the TPP.) The same year, a trio of economists published a landmark paper showing that free trade with China had cost about 2 million U.S. workers their jobs and devastated much of the Rust Belt, a phenomenon that became known as “the China shock.” Later research found that Trump had overperformed in counties that had been most heavily exposed to Chinese imports. The lesson was that although free trade brings widespread benefits, it also can inflict extremely concentrated costs—with potentially disastrous political ramifications.

Now out of government, Sullivan found himself searching for where his party had gone wrong. He met with manufacturing workers and labor-union officials who described the toll that shuttered factories and lost livelihoods had taken on the American middle class. He watched as China veered in an ever more authoritarian and aggressive direction even as it became more integrated into the global economy—the exact opposite of what free-traders had predicted. He sat at home during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic as the United States found itself facing shortages of supplies as basic as face masks and as essential as semiconductors. Eventually, he concluded that the old consensus was deeply flawed. “There were a number of these moments where it became clear that the world had changed,” Sullivan told me. “But our prescriptions for what to do about it had not been updated to account for the world we were now living in.”

Joe Biden, a longtime free-trade advocate, had undergone a similar awakening by the time he took office, in 2021. He appointed Sullivan as his national security adviser and tasked him with weaving the administration’s trade policy, domestic economic priorities, and foreign-policy agenda into a cohesive vision. In April 2023, Sullivan gave a speech outlining the contours of that vision, which he called a “new Washington consensus.” “The postulate that deep trade liberalization would help America export goods, not jobs and capacity, was a promise made but not kept,” Sullivan declared. Instead of deferring to the whims of the global free market, the U.S. government should play a more active role in creating good middle-class jobs, reducing economic dependence on geopolitical adversaries, seeding new industries crucial to national security, and building resilient supply chains. The centerpiece of the new consensus was the passage of major public investments in clean energy and semiconductor manufacturing.

[Franklin Foer: The new Washington Consensus]

For Wallach, now the director of Rethink Trade at the American Economic Liberties Project, the Sullivan speech was the ultimate validation. Finally, a Democratic administration was saying and doing the kinds of things she had spent decades advocating. But the administration remained internally divided over the use of outright protectionist measures; free-traders such as then–Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen frequently clashed with trade skeptics such as U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai. Biden quietly kept in place most of the tariffs that Trump had levied on China, but he began the final year of his first term without having added any new ones.

What changed the administration’s calculus was the looming prospect of a second China shock, this time in the very industries the administration was working so hard to build up. By 2024, after decades of strategic state subsidies, China was producing two-thirds of the world’s electric vehicles, three-quarters of the world’s electric batteries, and 90 percent of the world’s solar panels, and selling them for much cheaper than the corresponding American products.

To the administration, the danger was clear. Without intervention, the American auto industry, which had only just begun its own transition to EVs, could be wiped out by cheaper Chinese imports. Other clean-energy industries would be crushed before they had time to benefit from the government’s huge investments. The U.S. would become dependent on its biggest rival for some of the most important technologies in the world. Future demagogues would seize on the issue to win elections.

This nightmare scenario converted even longtime free-traders into tariff supporters. In March 2024, Yellen made a visit to the factory floor of Suniva, a Georgia-based firm that had been developing a cutting-edge process for manufacturing solar panels, only to file for bankruptcy in 2017 after Chinese panels began flooding the U.S. market. Biden’s clean-energy investments had helped the company reopen, but it was still years away from reaching the scale needed to compete with Chinese firms. “This was true across almost every clean-energy sector,” Yellen told me. “We felt we needed to be competitive in producing the energy sources of the future. But without protection, our companies would have stood no chance.”

Last May, the Biden administration announced tariffs on a handful of Chinese goods in “strategic sectors,” including 25 to 50 percent tariffs on batteries, solar panels, medical supplies, semiconductors, and certain steel and aluminum products, and 100 percent tariffs on electric vehicles. The restrictions represented what is sometimes called a “targeted tariffs” approach, rooted in the belief that a select few industries are important enough to be protected from foreign competition, even at the cost of higher prices. If China were allowed to totally dominate solar panels, semiconductors, and cars, then the U.S. would end up reliant on a geopolitical adversary for its energy, military, and transportation infrastructure. And if the government stood by while industry after industry experienced a second China shock, the economic and political consequences would be severe.

Supporters of the targeted approach recognized that tariffs are a blunt tool that must be used sparingly, in combination with other strategies to bolster American industry. “What the Biden team understood is you can’t just do tariffs,” Wallach told me. “You need investment to build capacity in a home. You need to incentivize factory building. You need to work with allies to diversify sources of goods. It’s a whole package.”

The Biden tariffs, limited though they were, really did signal the emergence of a new consensus in Washington. Congressional Democrats were almost universally supportive, while Republicans were largely silent. A move that would recently have been considered beyond the pale had become conventional wisdom.

Heading into the 2024 election, several polls found that majorities of voters supported tariffs. Today, after months of tariff-related economic chaos, nearly every credible survey finds the opposite. Support for free trade, meanwhile, has never been higher. In Gallup’s most recent survey, 81 percent of Americans said that they view international trade as an “opportunity” as opposed to a “threat”—a 20-point jump from just a year prior and the highest percentage since Gallup started asking the question, in the early 1990s. To free-market economists, Trump has proved what they have known all along: Trade restrictionism is always a bad idea.

This argument drives pro-tariff liberals crazy. To them, the notion that Trump’s policies would discredit tariffs in general is the equivalent of saying that the existence of fentanyl overdoses discredits taking Advil for a headache. Biden focused on a narrow set of goods from a single country; Trump has tariffed almost all goods from almost all countries. Biden’s tariffs were one piece of a broader industrial strategy that included massive public investments; Trump has no plans for new investments and has threatened to repeal the ones that Biden passed. Biden implemented tariffs carefully and gradually; Trump jacked up tariffs on China by 125 percentage points in one day, and has since modified his tariff policies too many times to count. Biden supplemented tariffs by deepening trade relations with allies; Trump has threatened to tariff America’s allies into submission. Biden’s tariffs provoked little to no retaliation from China and hardly registered in the stock market; Trump’s tariffs have triggered a full-blown trade war. “It’s strange to even consider these the same kind of policy,” Sullivan told me. “It’s like comparing a scalpel to a sledgehammer. They are totally different tools.”

[From the June 2025 issue: The coming economic nightmare]

Several Democrats have responded to Trump’s tariffs with a version of this argument. These include not just Rust Belt politicians (such as Representative Chris DeLuzio of Pennsylvania, who attacked Trump’s restrictions for being “chaotic” and “inconsistent” while acknowledging that tariffs remain a “powerful tool”) and outspoken progressive populists (such as Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren) but also the party’s leaders. “Tariffs, when properly utilized, have a role to play in trying to make sure that you have a competitive environment for our workers and our businesses,” House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries said in a recent interview.

To Wallach, statements like these capture just how much progress Democrats have made on trade policy. To other observers, however, they’re political lunacy. Democrats’ attempts at nuance on tariffs have been widely mocked as an example of their inability to capitalize on Trump’s mistakes. “As the American public was screaming, ‘Please, God, no!’ the Democrats were calmly whispering, ‘Yes, but,’” my colleague Jonathan Chait witheringly wrote. Or, as The New Republic’s Jason Linkins put it, “The dumbest thing Democrats could do right now is lend even a scintilla of credence to a bad president’s worst idea.”

In the eyes of pro-tariff liberals, however, something bigger is at stake than political-messaging tactics. They see the old free-trade establishment using the cover of Trump’s unpopular program to regain the territory they lost over the past decade. Free-market economists who oppose all trade restrictions have become fixtures on cable television. And some high-profile Democrats have started taking public stances that appear to be ripped from an Econ 101 textbook. “Tariffs are bad outright because they lead to higher prices and destroy American manufacturing,” Colorado Governor Jared Polis recently declared on X. “Trade is inherently good because both parties emerge better off from a consensual transaction.”

The pro-tariff liberals are afraid of where the debate is headed. “We can’t fall into this trap of thinking it’s either the Trump way or the Wall Street Journal–editorial-board way,” Sherrod Brown told me. “Neither of those options is good for American workers.”

Now Wallach is fighting to salvage her life’s work. She has spent the past few months writing op-ed after op-ed, memo after memo, lengthy X post after X post, practically begging her fellow liberals not to give up on tariffs just because Trump has given them a bad name. She has poured countless hours into meeting with members of Congress, union leaders, and environmental groups in an effort to build a durable liberal pro-tariff coalition.

But if Wallach and her allies are pushing against the side of an aircraft carrier, trying to nudge it in their preferred direction, Trump is holding the steering wheel. According to the monthly Conference Board survey, consumer confidence recently fell to its lowest point since April 2020, while expectations for the next six months fell to its lowest point since October 2011. That’s despite the fact that the brunt of the economic pain from Trump’s tariffs hasn’t even been felt yet. If this goes on, attempts to distinguish between good and bad tariffs might sound about as convincing as attempts to distinguish between good and bad bedbug infestations.

Still, Wallach remains stubbornly confident that her side will prevail. “I ultimately don’t think we’re going back to the old trade consensus,” she said. “Democrats saw what 40 years of free trade brought us. And under Biden, they saw that a different kind of approach can work. I really do believe that will be enough.”