The Danger of a Too-Open Mind

Perhaps being persuadable is overrated—at least if it means “coming to accept the unacceptable.”

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

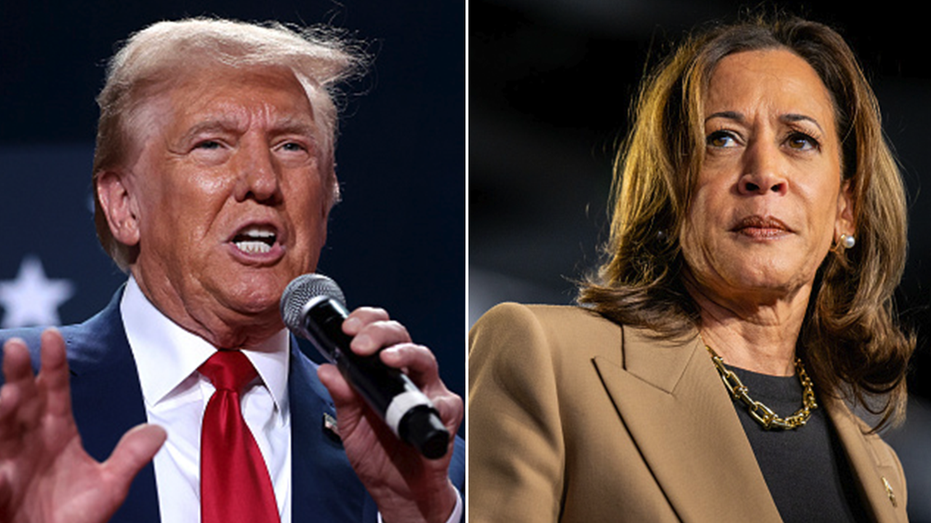

At a moment when just asking questions can feel synonymous with bad-faith arguments or conspiratorial thinking, one of the hardest things to hold on to might be an open mind. As Kieran Setiya wrote this week in The Atlantic on the subject of Julian Barnes’s new book, Changing My Mind, “If a functioning democracy is one in which people share a common pool of information and disagree in moderate, conciliatory ways, there are grounds for pessimism about its prospects.” But what should the civic-minded citizen do with that pessimism? Knowing about our tendency toward rationalization and confirmation bias, alongside the prevalence of misinformation, how do we know when, or whether, to change our minds?

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- What Shakespeare got right about PTSD

- The life of the mind can only get you so far

- The last great Yiddish novel

- “Coalescence,” a poem by Cameron Allan

Another article published this week presents a possible test case. The Yale law professor Justin Driver examines a new book, Integrated—and, more broadly, a surge of skepticism over the effects of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision that ordered the racial integration of American public schools. The book’s author, Noliwe Rooks, was “firmly in the traditional pro-Brown camp” as recently as five years ago, Driver writes. But America’s failure to accommodate Black children in predominantly white schools, combined with the continuing lack of resources in largely Black schools, led Rooks to conclude in her book that Brown was in fact “an attack on the pillars of Black life”: that integration, as carried out, has failed many Black children, while undermining the old system of strong Black schools.

Should this case of intellectual flexibility be celebrated? It certainly makes for a lively debate. Driver calls Rooks’s “disenchantment” with the ruling “entirely understandable,” but he sticks to his own belief that Brown has done more good than harm, and he makes a case for it. For example, Rooks portrays Washington, D.C.’s prestigious all-Black Dunbar High School as a hub of the community, staffed by proud and dedicated educators. Driver complicates the history of those “glory days” by quoting its most prominent graduates: “Much as they valued having talented, caring teachers, these men understood racial segregation intimately, and they detested it.” And he notes that, beyond changing education, “Brown fomented a broad-gauge racial revolution throughout American public life.” He demonstrates that we can absorb new information—in this case, evidence of the many shortcomings of American school integration—without forgetting the lessons of the past.

Barnes makes a similar case in Changing My Mind, a book that is, in fact, mostly about why the novelist hasn’t altered his opinions and ultimately doubts that trying to is worth it. To adopt new beliefs, he writes, we would have “to forget what we believed before, or at least forget with what passion and certainty we believed it.” Setiya chides Barnes for his view that, given our hardwired biases, we might want to give up on being swayed at all. But he concludes that such stubbornness is “not all bad.” Perhaps keeping an open mind is overrated—at least if it means “coming to accept the unacceptable,” as Setiya puts it. And how should a person determine what’s unacceptable? “When we fear that our environment will degrade,” Setiya writes, “we can record our fundamental values and beliefs so as not to forsake them later.” Once we know what our principles are, we can more easily weigh new information against our existing convictions. Without them, it would be easier to change our minds—but impossible to know when we’re right.

It’s Hard to Change Your Mind. A New Book Asks If You Should Even Try.

By Kieran Setiya

The novelist Julian Barnes doubts that we can ever really overcome our fixed beliefs. He should keep an open mind.

What to Read

Witness, by Whittaker Chambers

This 1952 memoir is still thrust in the hands of budding young conservatives, as a means of inculcating them into the movement. Published during an annus mirabilis for conservative treatises, just as the American right was beginning to emerge in its modern incarnation, Witness is draped in apocalyptic rhetoric about the battle for the future of mankind—a style that helped establish the Manichaean mentality of postwar conservatism. But the book is more than an example of an outlook: It tells a series of epic stories. Chambers narrates his time as an underground Communist activist in the ’30s, a fascinating tale of subterfuge. An even larger stretch of the book is devoted to one of the great spectacles in modern American politics, the Alger Hiss affair. In 1948, after defecting from his sect, Chambers delivered devastating testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee accusing Hiss, a former State Department official and a paragon of the liberal establishment, of being a Soviet spy. History vindicates Chambers’s version of events, and his propulsive storytelling withstands the test of time. — Franklin Foer

From our list: Six political memoirs worth reading

Out Next Week

_alon_harel_Alamy.jpg?#)