Yoko Ono Has Always Been More Than John Lennon’s Wife

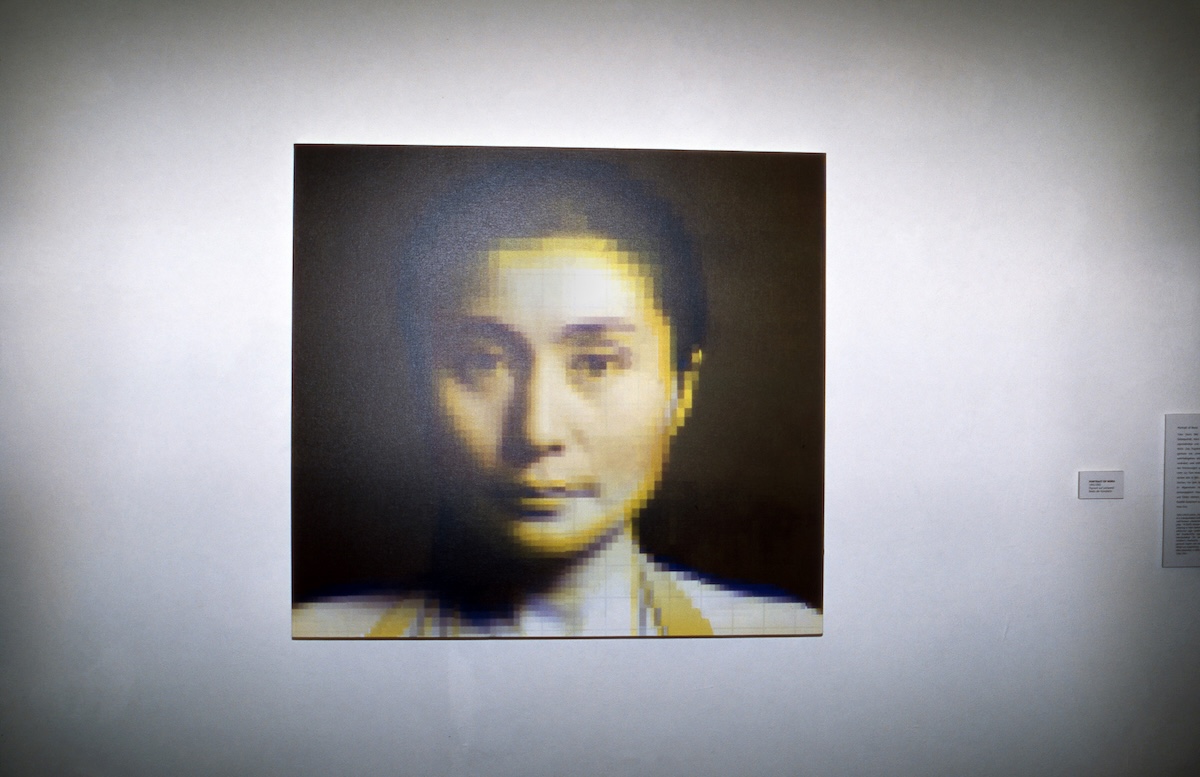

David Sheff was only 24 when he famously interviewed John Lennon and Yoko Ono for Playboy magazine in September of 1980. He had done a few celebrity interviews before, but none as big as that one. “They were as big as it gets in that world, in any world, actually,” Sheff tells me over a […]

David Sheff was only 24 when he famously interviewed John Lennon and Yoko Ono for Playboy magazine in September of 1980. He had done a few celebrity interviews before, but none as big as that one.

“They were as big as it gets in that world, in any world, actually,” Sheff tells me over a video call from his home in Northern California. “I was this young kid going in there with my little tape recorder, my little micro cassettes, and my notebook. And I walked into the Dakota, this formidable building, and before I met with John, I met with Yoko. I was sitting across from her and I was really intimidated and very nervous. And she didn’t make it easier for me.”

More from Spin:

- Outside Lands Welcomes Tyler, Hozier, Doja Cat

- Argentinian TRÍADA Show It Takes Three to Tango

- Flaming Lips, Modest Mouse Turn Back The Clock For Summer Tour

Sheff tells me he had to prove himself to her before speaking with Lennon. After reading his astrological and numerological charts, Ono “allowed him in the door.” When Sheff finally met with both of them for the initial interview, she transformed, he says. “That nervousness went away pretty quickly.”

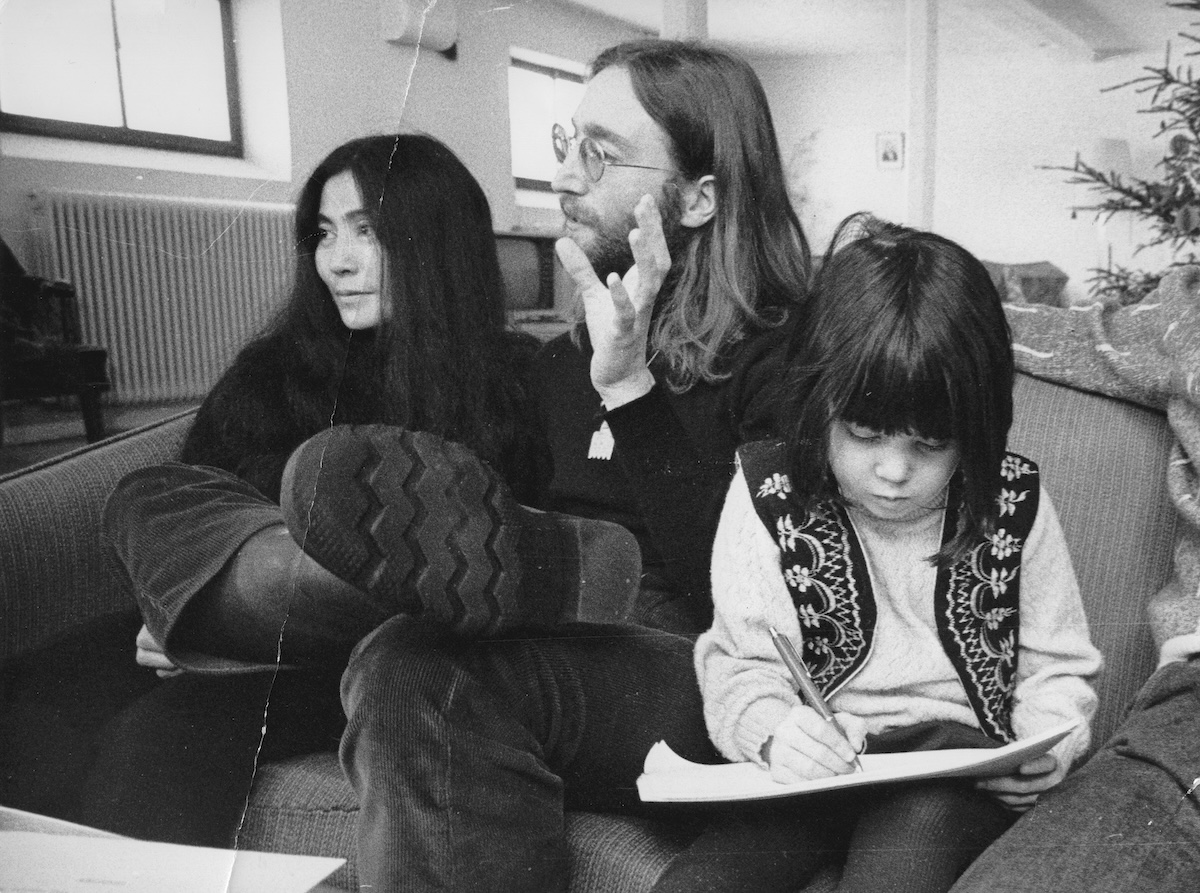

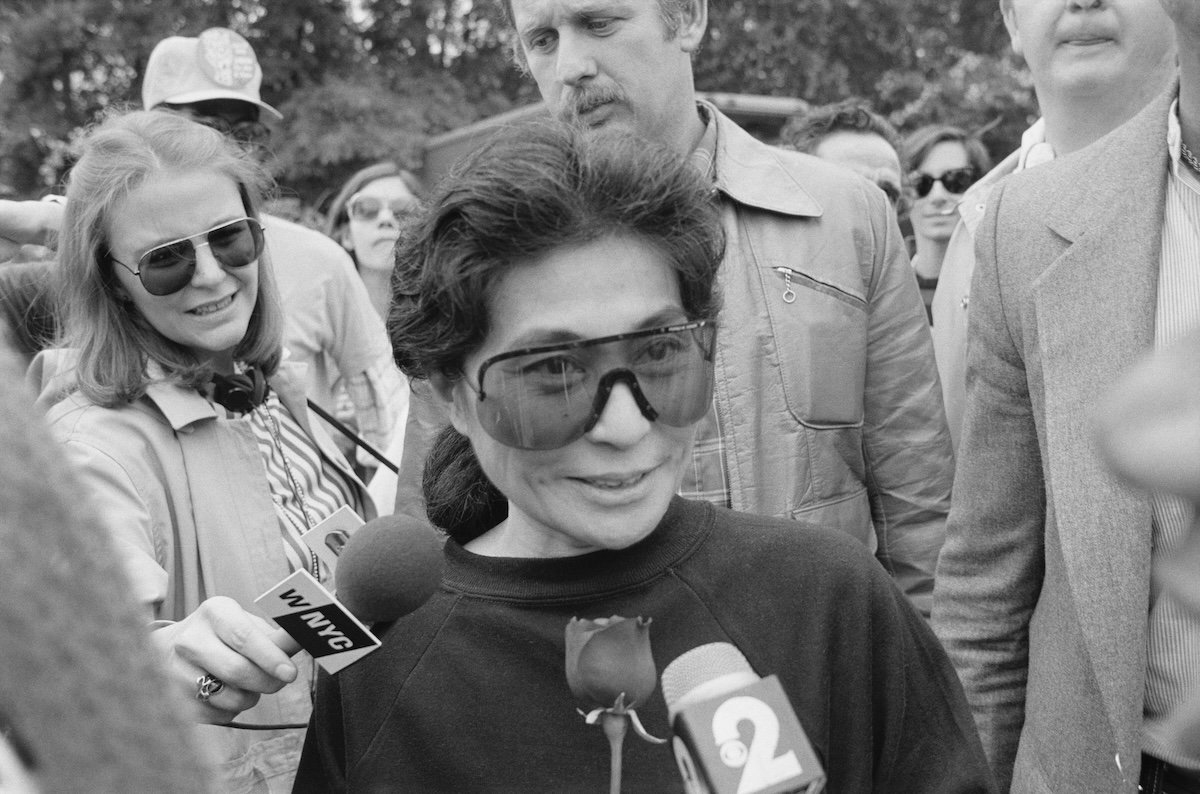

Sheff spent three weeks with Lennon and Ono. Almost three months later, on December 8, Lennon was tragically gunned down by Mark David Chapman.

The Playboy piece was published in the January 1981 issue, making it Lennon’s last public interview. After the famous Beatle’s murder, Sheff and Ono became close as she rebuilt her life, survived threats and betrayals, and went on to create groundbreaking art and music while campaigning for peace and other causes.

While hundreds of books have been written about Lennon and his impact on pop culture, Ono’s contributions have been generally attributed to being John Lennon’s wife. To some, Ono has been considered a seductress villain who manipulated her husband and broke up the Beatles.

The Beatles saga is one of the greatest stories ever told, but Ono’s part has been relegated to folklore—hidden in the Beatles’ formidable shadow, further obscured by flagrant misogyny and racism.

Lennon once described Ono as the world’s most famous unknown artist. “Everybody knows her name, but no one knows what she does.”

Drawing from his experiences and interviews with her, her family, closest friends, collaborators, and many others, Sheff’s new definitive biography of Ono’s life, Yoko, changes all of that.

Sheff, the author of multiple books, including the No. 1 New York Times bestselling memoir Beautiful Boy, chats with SPIN about his decades-long friendship with Ono and how he believes the public’s perception of her as an artist in her own right is changing.

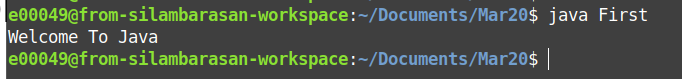

What made you want to write a biography of Yoko?

I’ve been kind of obsessed since I first heard the Beatles, especially John’s music. When I had that magic moment when an editor assigned me to interview John and Yoko and he said, “Do you have any way to get to them?” and I didn’t, of course, because I had no idea. But I said, “Sure, I’ll do it.” And I somehow was able to get them to agree to do the interview. But then that sort of drew me into their lives in a very personal way. And then the timing of that, before John died, made it even more intense. After John’s death, when I went to see her, that’s when I got to know her very well. It was a devastating time for her, of course. And I had spent such an intimate three weeks with her when she was with John at what I would say was the best time of her life. And I just continued to follow her work and I was one of the people who actually did love her singing, her music.

It was only a few years ago, probably about five years ago, when I was listening to her a lot. I mentioned in the book that I saw a license plate, a bumper sticker that said, “Still pissed at Yoko” at the same exact time that I was listening to one of her records and was thinking about how those old stories have just lasted and lasted and lasted, and the prejudices remain, and how much of her treatment was based on misogyny and racism. And all those things led me to assume that I’d missed something, that there must be this amazing biography out there that I had missed. Once I realized that wasn’t true, I got really excited about the idea of writing it to show much more of her than people knew. I proposed it and my editor was excited about it, too.

In your book’s introduction, you talk about your friendship with Yoko, and balancing that with a sense of objectivity because she is such a controversial figure in Beatles lore. How difficult was that for you?

It was maybe the toughest thing to do. I really do consider her a friend. She has been very supportive of me when I’ve gone through some of the toughest times in my life. And I got to know Sean [Lennon] really well and really care about him. So I would be unable to come in and write a completely objective book about her. But at the same time, I didn’t want to write a puff piece. So there was a fine line that I had to walk that went to my instincts as a journalist to tell the truth about a friend. There were times when I was unsure about how to proceed, and I just had to go back to this idea that I was committed to telling the real story.

First of all, I realized I had to disclose everything up front, which I did. So, I wasn’t going to pretend to be objective. But then the other thing is that they [Yoko and Sean] were devoted to the truth, and there was nothing they didn’t talk about. And so I felt that they’d somehow given me permission to go to places that were some of the trickier parts of their lives, things that maybe somebody else would’ve tried to hide. So, that made it somewhat easier for me.

I really appreciate how much you delved into Yoko’s early life and family, which gives perspective on why Yoko is the way she is, or at least how she comes across to the public.

She had a very difficult childhood, in spite of the fact that she was also incredibly privileged. Her great-grandfather was thought to be the richest man in Japan. So she grew up in extreme privilege. At the same time, she was like the poor little rich girl because she did not have the attention from her parents. She was pushed aside and raised by nannies and maids. And they were her companions. And she was very lonely and really isolated and in a lot of pain. And on top of that pain came the trauma of the war [World War II]. All their wealth didn’t protect them from the bombing and even from the food shortages.

And they were shipped out of Tokyo and went out to the country to Nagano Prefecture. Yoko, as a young child, I think she was 12 then, was responsible for taking care of her little brother and sister, and going through with a cart and pedaling their family goods—kimonos and a sewing machine—for rice. So she certainly didn’t have it easy. And then when she came back after the war, Tokyo had been devastated. And she was traumatized and devastated, and she suffered as a teenager. She had great depression. She tried to kill herself. And it was only when she finally got out of Japan and got to New York after dropping out of college in Tokyo and then starting college at Sarah Lawrence in New York that she finally found a replacement family for her own family, which was the family of artists that she was immersed in when she finally got involved in the avant garde scene of New York City.

Did you feel a sense of having to defend Yoko when writing her story, much in the way that John had to?

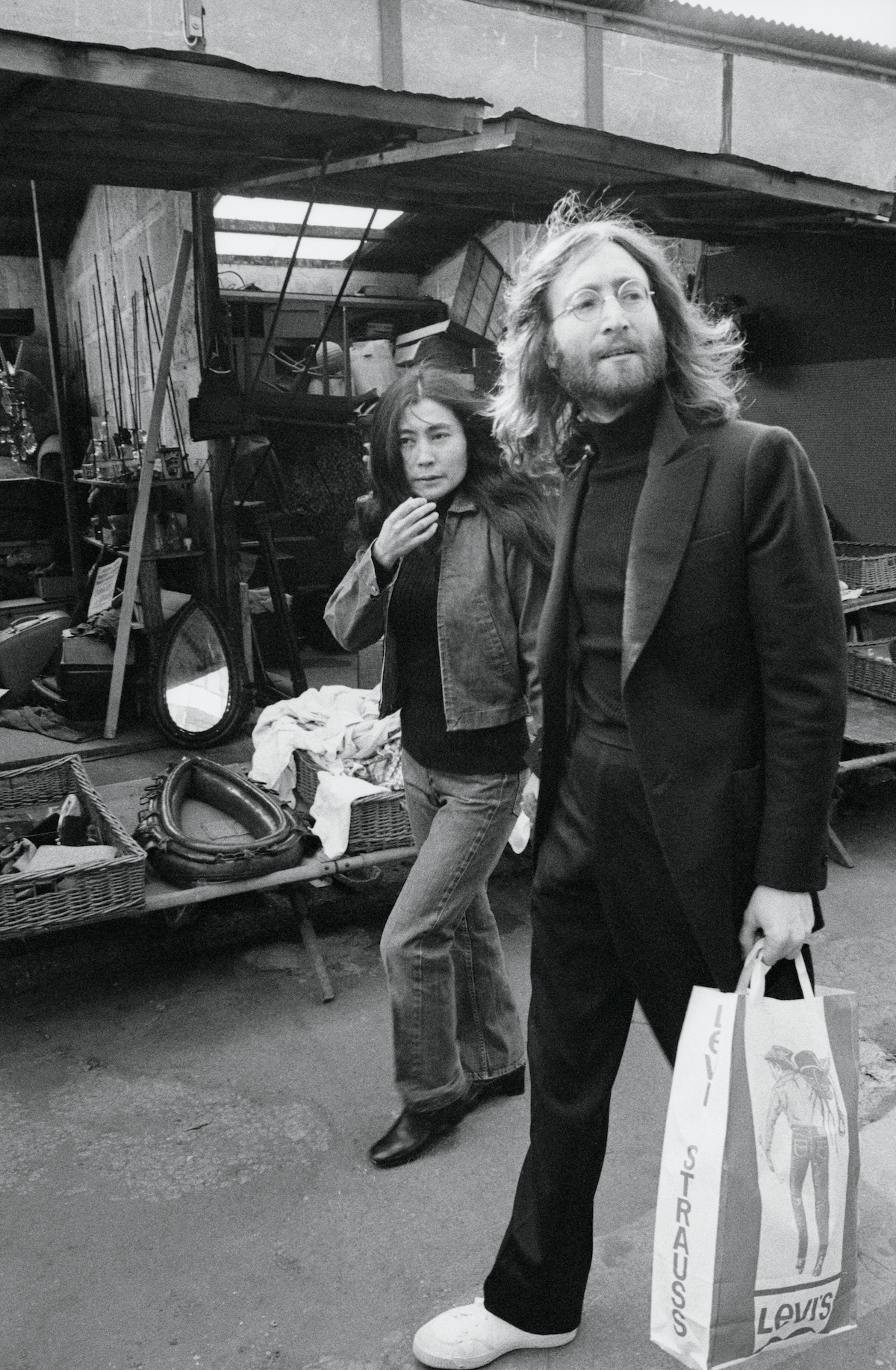

That’s a really interesting question because a lot of what John did was to try to defend her and try to show to others, to show to all of us, what he saw in her for sure. I guess I did see that as part of my job…to get past the tired story of her being the one who broke up the Beatles and destroying John’s art and destroying his marriage [to Cynthia]. The tabloids in London were describing her as the most hated person in the world. Part of my purpose was to show, in a sense, what John saw in her, which was, in addition to being a much more complicated person, looking at the world in a really unique way, one that inspired him and inspired me. But also to get people to see her work. Because I think once you look at her work, you kind of get her in a new way. And you also get what John was trying to show everybody. He was completely transformed by her work from the moment he met her at the art gallery at Indica in London when he saw her work for the first time.

Before reading your book, I always assumed that John was the one who influenced Yoko musically. But it sounds like it’s the opposite—that Yoko was quite the influence on John post-Beatles.

Yeah, without a doubt. When he connected with her, he was freed. He was unhappy at the end of the Beatles period, of course. And he felt this burden of obligation, and he was depressed. He still was inspired by creating music, but the work that came out after that was completely different. And so much of it was, you could just see Yoko in it, and you could see it in the lyrics and songs like “Imagine” and “Give Peace a Chance.” I tell the story, of course, about how people still think of “Imagine” as a John Lennon song. But the fact that she was the co-writer of that song, and John didn’t give her credit at first, he said, because it was sexism and he admitted it. That song is a synthesis of Yoko’s thinking and her art. So many of the love songs that he wrote were devoted to Yoko, but also in so many of the live performances, she inspired him to go out there in places that he loved. That was another thing that he wanted people to understand. He talked about when he performed with her in Toronto and the other big concerts where he just played guitar and she did her vocalizing, that he described as some of the most exciting musical moments of his life. It gave him a kind of peace that he had never had before in his life. And as an artist, it really inspired him. And he did some performance art along with her, all completely based on Yoko’s thinking and her philosophy about life and art. And then in the music as well, I mean, starting with “Revolution 9,” which is pure Yoko. I mean, there was nothing as experimental and wild and out there and controversial on any Beatles album before that.

Do you think John was in a codependent relationship with Yoko? Is there a connection between his relationship with Yoko and his dysfunctional childhood, and the strict upbringing of his Aunt Mimi?

Yeah, I think that he would’ve probably been the first to admit it, if that was a word that we were using at that point, He said Yoko saved his life. And he said that when they had their separation, that was when he realized for the first time that the shoe was on the other foot. In fact, he always thought he was the powerful one. He was the guy. He was the Beatle. He was John Lennon. And she was the one who was dependent on him. But he realized it was the opposite; that he was dependent on her. In my [Playboy] interview, he talked about it a lot. He said, “She’s the teacher; I’m the pupil. She taught me everything I know.” I remember those words. The famous cover of Rolling Stone—the last photograph taken of the two of them together before John was killed, he’s naked and wrapped around Yoko in the fetal position, and she has her clothes on. And he said that was what described their relationship; the man letting down his guard, being dependent on the woman. I think it was amazing, given the chip on his shoulder that he had because of the experience that you were describing of the way he was raised. He intentionally went against that whole macho training and education that he had. And Yoko was blamed for that. I think that was part of the thing about Yoko coming in and taking over and being aggressive; she’s the one who broke up his marriage and she’s the one who pursued him and all that kind of stuff. But it really wasn’t true. She gave him what he described as a lifeboat at a time when he was drowning. I think codependence really does describe their relationship in many ways. And again, I don’t think it’s something that he would object to.

You write about Yoko’s reliance on astrology and numerology to help her make important business and life decisions. Did she ever talk about why she took these beliefs so seriously?

A little. It was more part of her family and her culture when she was growing up. I think her mother was involved in some astrology and had numerologists and all that stuff. But for Yoko, initially it was just another system of viewing the world. And she talked about it to me once, about how it allowed her, when she was doing business, to see things in a different perspective, and giving her, she felt, an advantage because she didn’t have the same training as the people she was up against—the lawyers and the business people. It put people off guard a little bit.

But I think that that all was only part of the story. I think even before John died, she believed in that stuff in a very deep way, and she needed it. But then after John died, she was so traumatized and so devastated that she needed something to help her keep going, and also something to explain what had happened to her. And so her involvement with psychics and astrology and numerology, they took over in a way that was sad and disturbing because it was clearly out of a place of deep need. It was also understandable how someone suffering the death of a loved one might embrace religion as a way to get through.

I thought you did a really good job of not sugarcoating Yoko’s mental state in the aftermath of John’s death, especially when it came to Sean.

I wrote about some of the really heartbreaking times when she would have seances, trying to connect with John and believing that she did it at some point. And one time, you know, maybe the most heartbreaking one of all was the time that I wrote about when she thought Sean, because he was a child, would have more access to the spiritual world. And so she did a seance kind of thing with Sean to communicate with John. And Sean, being a child, wanting to please his mother, pretended that he was actually being a medium so Yoko could communicate with his dad. I mean, it was sad.

When I was done reading the book, I felt like I had a new appreciation for who Yoko is as a person.

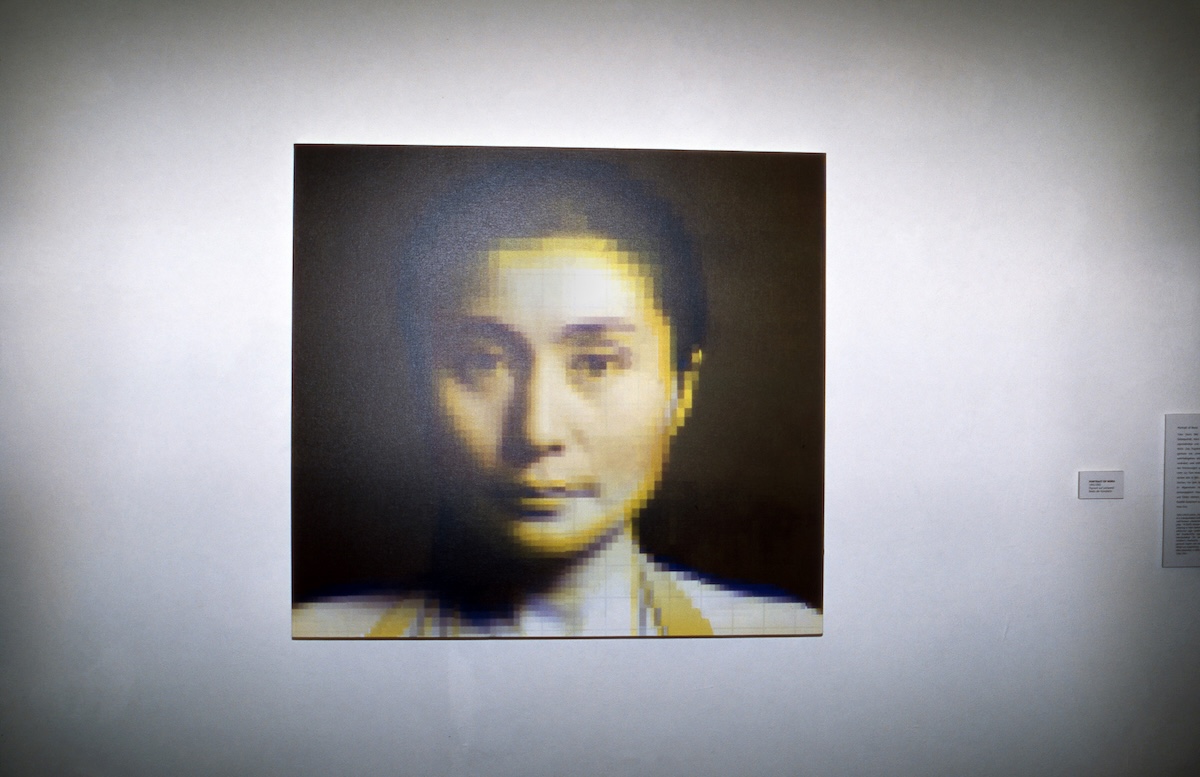

Well, that means a lot because that was really part of the goal. When you look at her work, one of the things I do at the very beginning is I talk about her instruction pieces that she was doing very, very early; the way that she would create a self portrait that actually was a mirror. Or the box of smiles where you’d open up this box and there was a mirror inside, and you’d see yourself and you’d smile, all those kinds of pieces. The work itself was so exciting to go into, and at one point, the book ended up being about 110,000 words or something like that, but at one point I had about 800,000 words. But part of that was that I really wanted to cover the art and music. They’re so beautiful in so many ways, and some of them are really disturbing, and some of them are really funny, and some of them are really inspiring in a way that they make you look at the world a little bit differently. That was one of the fun parts, and it was really painful having to leave so much of her work out of it. I kept in what I considered some of my favorite pieces, and some of the ones that I felt like were the most important. She just had this show at the Tate in London and they had [more than] 200 of her pieces in there, which was a lot in an exhibition. But that was just a fraction of her life’s work.

Lots of people, as you state in your book, blame Yoko for the breakup of the Beatles. Do you think fans’ opinions of Yoko have changed over the years?

Over the years, people would ask me what I was writing, and I was like, “I’m writing this biography of Yoko.” And it was amazing how consistent the reaction was. People still think of her as the one who broke up the Beatles, as this sort of shrewish, evil force that came into John’s life and destroyed his creativity, in spite of the fact that, because of Yoko’s influence, he was as creative as he’d ever been in his life. And arguably he created his best work after the Beatles, although a lot of people might disagree with me on that. But certainly as you know, he believed that his work post-Beatles was the best work that he’d ever done.

So there has been a big shift in the way that people view her in the art world, where her work has been acknowledged as being incredibly profound and pioneering. As a conceptual artist, she’s kind of gotten her due and she’s had retrospectives, not just this one in London, but she’s had them around the world. So I think that the art world has gotten over the fact that Yoko was more than Mrs. Lennon. She was an important artist in her own right.

I think that there is a part of the music world that really gets her work. And when they started to reissue a lot of her works in this box set called OnoBox, where they put out six CDs of her work and then reissued some of her early works, I think that there was a reevaluation. I talk about people kind of getting it, and some of the reviews were as if they were apologies for the fact that people didn’t really listen to her with objectivity at the beginning and all they heard was the screaming. So, I think in the art and music worlds, the insiders in those worlds, the people who really know a lot and really have studied the work, the view of her has changed.

But I do think that part of what I had to navigate also was, who is my audience? Am I talking to the people in the art world who know her work? Or am I talking to the people in the music world who know her work? Or am I talking to the people out there who still think of Yoko as the one who broke up the Beatles? I tried to do it all.

So, that was a long answer to just saying that I still think that there is a huge misunderstanding of her as a person. The prejudices remain, and that goes back to the very first question, why I wrote the book, which was to try to change that a little bit. And if it has any impact on that at all, then it’ll at least be a success in that way, I hope.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.