How Trump can strengthen the US Navy

The idea of the Shipyard Accountability and Workforce Support plan is to allow the Navy and its shipbuilders more flexibility in how they spend money.

When you think of the U.S. Navy, you probably think of historical conquests against Barbary Pirates or heroism on the high seas. But one key thing our Navy needs today to thrive is a little more mundane. If we want a healthy and growing naval shipbuilding industrial base, we must change the accounting practices used at the Pentagon and the Office of Management and Budget.

The Navy proposed the Shipyard Accountability and Workforce Support plan last year to help financially troubled shipbuilders get healthier within existing budgetary resources. But the Biden administration shot down the idea on the grounds that it moved money around too much within the shipbuilding budget, after Congress had firmed up the earlier plan in its annual authorization and appropriations bills.

Despite my five years of experience a generation ago at the Congressional Budget Office, I do not have the ability to dispute OMB’s decision on the technical merits. Nor was there anything sinister about the decision. But it does appear that a plan hatched in good faith by the Navy itself to make naval shipbuilding dollars go further — for example, for the construction of attack submarines — was shot down on what seems to me a technicality.

The Trump administration could make taxpayers’ dollars go further and get America closer to its goal of building more than two attack submarines per year (today’s rate is closer to 1.5) by adopting this idea. Other parts of the U.S. naval shipbuilding base could benefit from this rule change as well.

If nothing else, the proposal is worth a second look.

The U.S. Navy remains the best in the world. Although its ship count is now exceeded by China’s by about 100 vessels, America’s ships are generally much better. Its aircraft carriers are far more capable and numerous. Its amphibious ships provide a power-projection capability that China cannot begin to rival. Its attack submarines are quieter and possess longer ranges on average (since all of ours are nuclear-powered).

Overall, the American naval fleet also has twice the aggregate tonnage of China’s. In other words, even though we have fewer ships, they are much bigger on average. More importantly, the U.S. Navy has better missile defense and a far longer track-record of seamanship and long-distance operations.

But China has advantages, too, beyond ship count. Its commercial shipbuilding sector is now much stronger than ours. A war fought in the western Pacific would give China enormous advantages of proximity. Its naval tasks are not complicated by the need to worry about multiple overseas obligations and theaters at a given time. And its government will not drive its most important national shipbuilding industries close to the edge of financial insolvency.

I am not suggesting that America’s remaining big shipbuilders are near collapse, but they are struggling to hold onto workers, much less expand their workforces. Their profit-margins are modest. American hopes of building a larger Navy under present conditions, as national defense strategies have advocated for four straight presidencies (two from each party), are not being realized.

We should be less concerned about the overall size of the Navy than about its asymmetrically crucial attack submarine force. These 50 or so vessels in the Navy today give us global reach, more or less with impunity. No one can track our subs in most of the oceans. They remain highly lethal — for example in the context of any Chinese attempt to seize Taiwan with an invasion fleet.

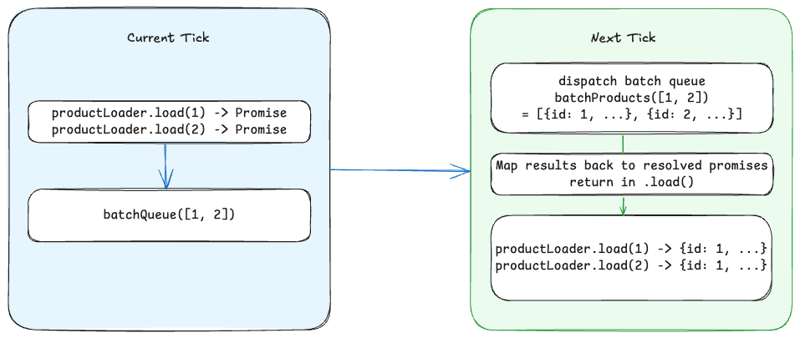

Right now, when the Navy signs a contract with a shipbuilder, the two parties agree on the total price in year one of the contract, but it is then paid out to the shipbuilder over the next three to six years. Since the amount of money has already been agreed to, inflation can leave the shipbuilder vulnerable to shocks from which it cannot easily recover over the contract's duration. Nor can it reprogram funding, for example, to rebuild and improve shipbuilding capacity, within the duration of such a contract.

The idea of the Shipyard Accountability and Workforce Support plan is to give the Navy and its shipbuilders more flexibility in how they spend money so that, when conditions change over the course of contracts, they can change their approach.

Under the plan, what are called “service and support” salary costs for a given year would be paid out of the funds provided by Congress for that year for all ships under construction, as with other Department of Defense procurements. Right now, funds for each ship are part into a sort of government escrow account and disbursed over the course of any given ship’s construction, which reinforces the vulnerability to inflation.

Military accounting practices are a lot less sexy than heroics at sea. But they really might matter for America’s grand strategy — and for securing peace through strength in the years to come.

Michael O’Hanlon is the Phil Knight Chair in Defense and Strategy at the Brookings Institution and author of “Military History for the Modern Strategist: America’s Major Wars Since 1861.”