Even Netflix Can’t Escape the <em>Black Mirror </em>Treatment

The sci-fi series takes aim at a very familiar target in its new season.

Black Mirror has never been subtle. Charlie Brooker’s famously bleak Netflix sci-fi series has skewered the role of technology in our lives—dating apps, surveillance culture, social media—across its seven seasons; it has shown us how our overreliance on the convenience of the digital world can harm the real one. Black Mirror is also often self-referential to a fault, dotting its episodes with Easter eggs to other installments, building a large shared universe. In its seventh season, the show’s meta-textual reflexes hit closer to home: This time, the target is streaming platforms, just like the one viewers use to watch the show.

The series’ take on the subscription-service economy is clear from the first episode. “Common People” is a tragicomedy following Amanda (played by Rashida Jones), who was recently diagnosed with a brain tumor, and her husband, Mike (Chris O’Dowd). The couple sign over their lives to the medtech start-up Rivermind, which digitally preserves part of Amanda’s consciousness following an emergency operation. Rivermind will upload Amanda’s mind back into her brain, which has been permanently altered by the surgery, so that she can live a normal existence—for a membership fee.

The service comes with some minor inconveniences, like a limited geographic coverage area and a lengthy, required shutdown phase. Eventually, Rivermind encourages its users to upgrade to higher pricing tiers with more perks, making life unbearable for those who don’t. Unable to afford the more expensive options, Amanda begins to deteriorate: She sleeps even more, for up to 12 hours a day; she abruptly recites advertisements for random products, including Christian counseling websites and erectile-dysfunction “cures,” with no memory of doing so. Amanda and Mike begrudgingly sign up for Rivermind Plus, even as the monthly fee continues to climb, which in turn pushes Mike toward unpleasant money-making schemes in order to keep their membership.

[Read: When a show about the future is stuck in place]

Rivermind is as damning a model of “enshittification”—the colloquial term for the gradual degradation of services over time to maximize profits—as Black Mirror has ever envisioned. What happens to Amanda is also an all-too-familiar experience for anyone who has ever signed up for, say, a streaming service, only for everything they liked about it to suddenly be walled off behind progressively higher prices. In Amanda’s case, her life hangs in the balance, and she and Mike ultimately must decide whether living like this is worth all the trouble.

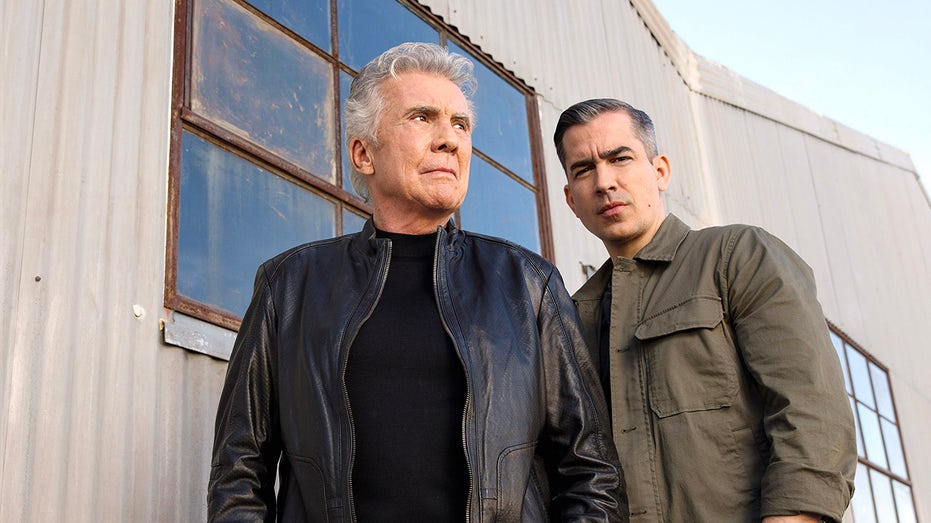

The season finale, “USS Callister: Into Infinity,” has a similarly vicious angle on the monetization of stuff. A sequel to the charmingly retro Season 4 premiere, “USS Callister,” the story picks up some time after the protagonists—digitized clones of actual people who are stuck inside an immersive online multiplayer video game called Infinity—have become content pirates: The game’s parent company has monetized everything, requiring players to purchase “credits” to access in-game features. As avatars without any real-world funds, however, the clones can’t purchase any of the necessary credits—meaning they can’t afford to even fly their spaceship without stealing other players’ in-game money. A slight annoyance to gamers in the real world is a genuine “cost of existing crisis,” as one of the ship’s crew members, Elena (Milanka Brooks), explains, for those trapped within the game. If the team doesn’t have enough credits to fly, they can’t escape from danger. And while regular avatars can just respawn after getting shot with a laser cannon, if any of the Callister’s crew dies in the game, they’re dead for good.

That’s stressful enough, but the episode’s sharpest critique is in its portrayal of the parent company’s CEO, James Walton (Jimmi Simpson), who has eyes only for profit and is incensed at the thought of freeloaders playing without paying; when he finally enters the game and interacts with the crew of the Callister—human beings whose lives are at stake—his first instinct is to open fire on them. In an extreme fashion, the murderous, bootlegger-hunting executive caricatures how streamers have introduced progressively tighter restrictions on online piracy and password-sharing while raising prices on as many features as possible.

[Read: Netflix is a business, not a movement]

This isn’t the first time Black Mirror’s near-future alternate universe has targeted the streaming-media ecosystem. The Season 6 premiere, “Joan Is Awful,” featured a Netflix-esque service called Streamberry; the company’s predatory terms and conditions entitle it to auto-generate television episodes based on the lives of Streamberry’s subscribers. The episodes are decidedly unflattering and yet undeniably popular; the outrage stirred up by them, as any internet user understands, begets attention that’s ultimately useful to the company. But they also cause real-world, irrevocable damage, as everything that Streamberry’s subscribers do—and everyone they interact with—becomes fodder for the streamer’s new hit program. The satire is among Black Mirror’s bluntest, a darkly funny exploration of the ramifications of bespoke storytelling.

The new season takes the idea a step further. In an ever more app-based world, a future in which the decision to subscribe becomes a life-and-death matter is not all that difficult to imagine. We pay for the privilege of using the gyms of our choice, driving our cars, listening to music, ordering household items, and accessing medical care. Subscription services dole out to their users the movies and shows they watch and the video games they play—all of which can disappear on the whims of their rights-holders. As for the denizens of Black Mirror, evil has never been more banal; it’s woven into their miserable lives via money-sucking tiers of convenience.