Education is our greatest export — cancelling student visas is a grave mistake

While the Trump administration has embroiled the U.S. in an all-out trade war because of what it says are unfair trade deficits, it is simultaneously causing irrevocable harm to our most valuable export: education.

While the Trump administration has embroiled the U.S. in an all-out trade war because of what it says are unfair trade deficits, it is simultaneously causing irrevocable harm to our most valuable export: education.

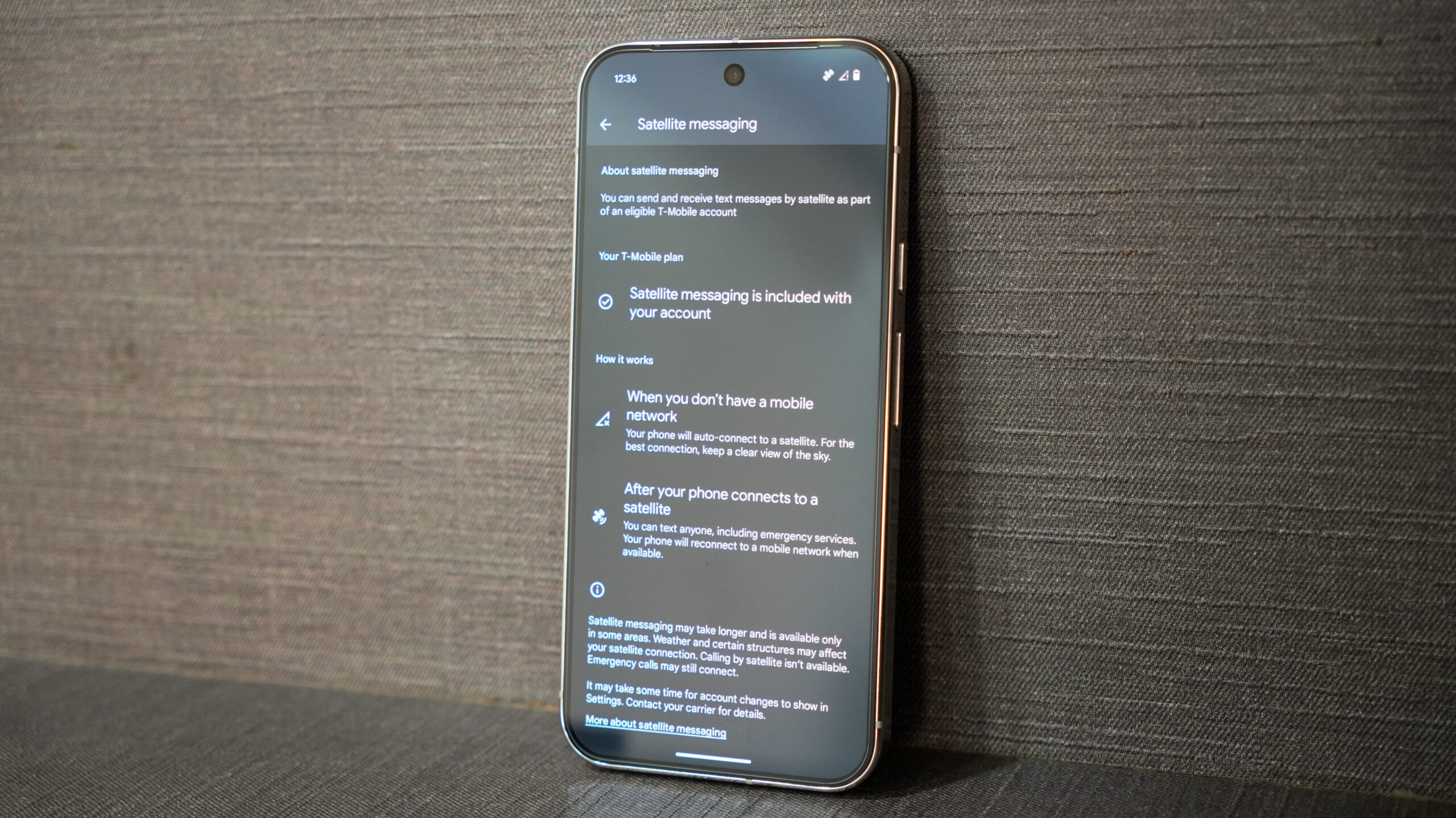

For nearly a month, at college campuses across the country, hundreds of international students’ visas were abruptly terminated. This sudden shift in policy — just as suddenly reversed this week, and with just as little explanation — is making our international students increasingly anxious about their future hopes and dreams.

Prospective foreign students have started questioning whether they should go elsewhere to study. These bright, young students are not going to stop learning, innovating and changing the world because we don’t provide a secure environment — they are just going to stop doing it here.

There are over 1 million international students in the U.S., the majority of whom pay hefty tuition to study here. They are a boon to America because of the businesses and innovations they create that help keep this country at the forefront of science and technology. Still others return to work in their home governments, and their knowledge of the U.S. market economy, democratic values and culture from studying here makes them better leaders and ambassadors, while their networks serve to maintain ties with the United States.

Moreover, the billions of dollars they pay in tuition payments are an export, helping to reduce the much-maligned trade deficit while subsidizing education for Americans.

Nearly half of the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are immigrants or children of immigrants, many of whom came here to study in the United States. Take for example, the largest five companies in the world by market value, all of which are American. Of those, three companies are currently led by foreigners who studied in the U.S.: Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, is Indian-born and came to the U.S. to study computer science at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and later earned an MBA at the University of Chicago; Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, was born in Taiwan and studied at Oregon State and years later earned a masters in electrical engineering at Stanford; Pichai Sundararajan, CEO at Google, is Indian-born and came to the United States to study engineering at Stanford and also earned an MBA at Wharton.

It is not just CEOs. Founders of Fortune 500 companies are also disproportionately immigrants who studied in the U.S. In addition, the share of U.S.-resident Nobel prize winners in chemistry, medicine and physics that are foreign born, most of whom studied in the U.S., is also well above their share in the population. These extraordinary business and scientific leaders keep the U.S. at the technological frontier.

Educating the best and the brightest from around the world also promotes U.S. foreign policy. More than 200 foreign heads of state spent time studying in the U.S., including several of our most important allies and friends. Current leaders who studied in the U.S. include Claudia Sheinbaum of Mexico, who spent three years at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory working a Ph.D. in energy engineering; Mark Carney of Canada, who attended Harvard for his undergraduate degree; and Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, who earned a master’s degree at MIT. Numerous economic, finance and foreign ministers were also educated in the U.S.

By attracting future leaders, the U.S. higher education system expands the global knowledge of U.S. political and economic institutions, as well as our culture. Moreover, international education is probably the only foreign policy instrument that doesn’t cost a cent to U.S. taxpayers.

Finally, most people do not think of education as an export, but it is. The U.S. exports over $50 billion in education services annually, a similar value to motor vehicle exports, which totaled $57 billion in 2024.

The income from education sales comes from the many foreign students who pay to be educated here. Like purchasing a car made in the U.S., foreigners are paying for degrees made in America. And unlike autos, many of whose parts come from abroad and do not create U.S. jobs, the value added in education exports is almost entirely domestic, implying that its direct effect on the U.S. economy is larger. Moreover, the income from foreigners enables U.S. institutions to provide subsidized education to Americans, creating additional positive spillovers to the U.S. economy.

While U.S. higher education is not perfect, it is the best in the world. Irrespective of where rankings are being compiled, at least half of the top 20 universities worldwide are in the U.S. (see for example, QS rankings from the U.K.). Attracting foreign students expands U.S. reach — economically, politically and culturally. It also helps to balance our trade deficit and subsidize education for Americans.

Unfortunately, the chilling effect on studying here from sudden, unexplained student visa terminations, not to mention lost federal funding for research, will be bad for the country and may be hard to reverse. Foreigners won’t stop looking to study abroad, but their talent will contribute to innovation in other countries and their knowledge of the U.S. will decline. Attracting international students is perhaps the only U.S. foreign policy tool that on net expands domestic innovation and the U.S. economy while costing nothing to American taxpayers.

Caroline Freund is dean of the School of Global Policy and Strategy at UC San Diego and a former director for Trade, Investment, and Competitiveness at the World Bank.