Dwyane Wade’s Greatest Challenge

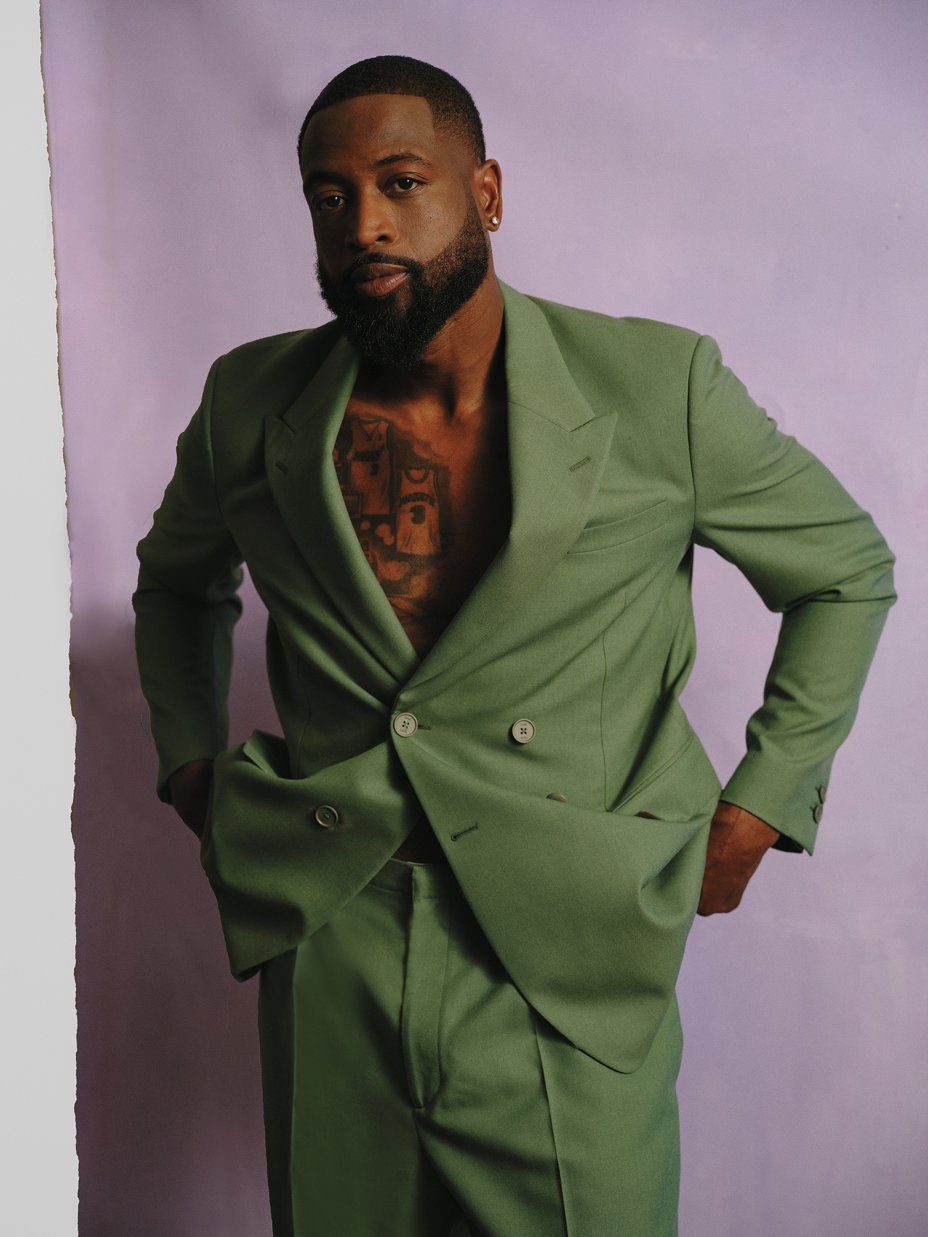

The Hall of Famer reached the highest heights of the basketball world. Now he’s figuring out the type of man and father he wants to be.

Photographs by Arielle Bobb-Willis

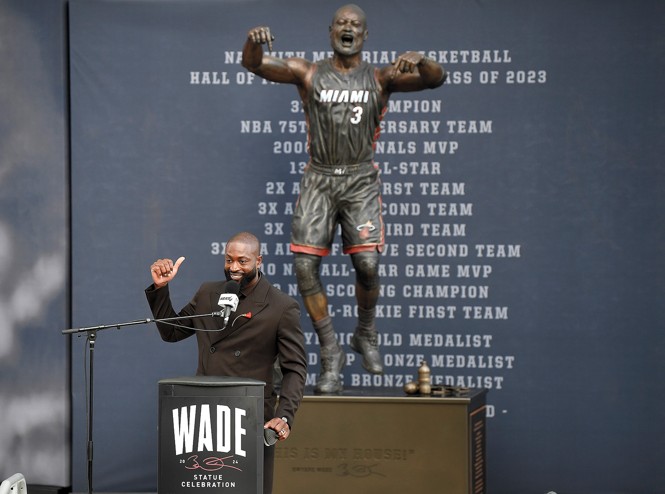

On a Sunday in October, a group of spectators gathered outside the Kaseya Center, the home of the Miami Heat. They sat in rows of chairs, arranged in a half circle. The crowd was there for the unveiling of a statue of Dwyane Wade, the superstar who had led the team to three NBA championships.

I wasn’t enough of a VIP to get a seat, so I found a spot on a gate during the unveiling, behind Wade and his family. I knew he had been anxiously awaiting the day. I’d watched, eight months earlier, as he’d paced around an early clay model in the sculptors’ studio, asking detailed questions—about the definition of his arms and legs, the way his jersey would be rendered. I knew how much this statue meant to him. And I knew he thought it captured him, as a player, perfectly.

The statue was made by Rotblatt Amrany Studio, a firm that has designed monuments to some of the most well-known athletes in America: Ernie Banks, Barry Sanders, Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant. When I’d visited the studio, in the Chicago suburbs, the sculpture of Wade ended at the wrists. I’d asked a member of the studio’s team where the hands were; he’d explained that the sculptors still needed more reference photos. “Wade has really, really big hands,” he’d said. “The biggest hands on a human that I ever saw.”

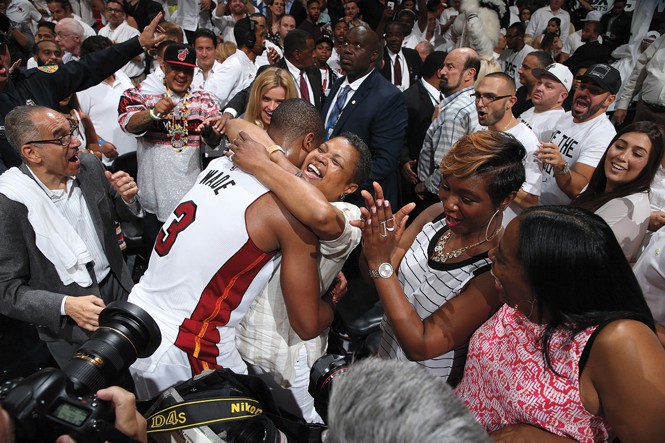

At the unveiling, flames shot up into the air and two black panels that had been concealing the statue slid apart. When the smoke cleared, there it was: a bronze behemoth, muscles rippling, Heat jersey clinging to the torso, hands appropriately disproportionate. The sculpture was based on a moment in a 2009 game against the Chicago Bulls. In the second overtime, Wade stole the ball and made a running, game-winning three-pointer as time expired. He then leaped onto the scorers’ table and yelled, “This is my house!” The face of the sculpture was a rictus of fury, with furrowed eyebrows and bared teeth. It also looked nothing like Dwyane Wade.

[Read: The worst statue in the history of sports]

Wade took the podium and shook his head in awe. “Who is that guy?” he said. The comment was intended as a statement of humility—I can’t believe that’s me—but laughter rippled through the crowd. “I don’t know who that guy is either,” someone near me whispered. On social media, the statue was immediately mocked. “Why they make Dwyane Wade look like Laurence Fishburne?” one sports reporter posted on X. Others compared the likeness to Thanos, or to the villain from The Mask.

To Wade, if the sculpture looked strange or monstrous, it befitted that moment in his career: an outburst of raw competitive energy, a pure expression of the rage that had driven him on the court. “It’s not a beauty shot of me,” he later told me.

Wade took the response to the statue in stride. “I saw some funny shit along the way about it,” he said. “That’s just the world we live in, man.” But perhaps behind the jokes was a recognition of a different kind of dissonance. Wade’s public image today is far removed from that 2009 moment, so much so that the two can be hard to reconcile. Maybe it wasn’t just the statue that was strange. Maybe people didn’t quite recognize the person the statue was meant to immortalize.

A year earlier, as I prepared to meet Wade for the first time, my usual barber took his wife on a cruise. I needed a cut, so I had to do the unthinkable: trust a stranger with my thinning hairline. I wandered into an unfamiliar barbershop in my hometown of Baltimore. The vibe of the spot was revolutionary; the walls were lined with faded posters of Malcolm X, Huey P. Newton, Chuck D, Nas. The barbers all wore dashikis or T-shirts that celebrated the motherland.

The man who stepped up to cut my hair told me his name was Power. Just Power. We made small talk, other guys chiming in. Eventually, as barbershop conversations do, the talk drifted to the NBA, and how the NBA of today is nowhere near as hard as it used to be. We talked about the days when Michael Jordan would get assaulted by the “Bad Boy” Pistons and still drop 50, about how you can barely touch another player nowadays without being ejected.

[Read: How the economists took over the NBA]

“Them kids softer than baby shit!” a UPS driver with a tight gray afro said. “I can play in the league now!” We all laughed.

I couldn’t help myself. I mentioned that I had an interview scheduled with Dwyane Wade. On the court, Wade had been one of the last avatars of the old-school way of hooping we’d just been reminiscing about, a warrior who played hurt and held grudges. But at the mention of Wade, the mood in the room immediately shifted; all around me, eyebrows raised. “Be careful around those Hollywood Negroes, brother,” Power warned me in a low tone. “Wade used to be a good brother. He hit Hollywood and he changed.”

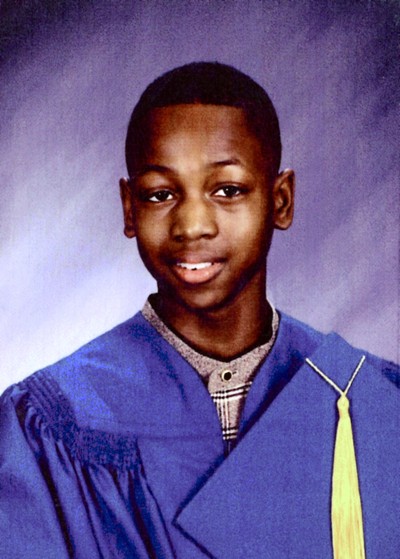

Wade has the kind of NBA origin story that would ordinarily make him a hero in a room like that one. He grew up on the South Side of Chicago, at the corner of 59th Street and South Prairie Avenue. His mother, Jolinda, struggled with drug addiction. The police raided their apartment so often that it became a familiar routine: Wade and his older sister Tragil Wade would escape through a back door and scale an outdoor stairway to their grandmother’s back porch, on the top floor of the same building, where they could hide. Other times, Jolinda wouldn’t come home. Wade could never sleep well when she was in the street, so even as a kid, he would sit outside late at night, waiting for her.

He was too young to understand why chaos reigned in his home and community, but Wade found early on that basketball was the perfect way to disappear, to get lost in something that demanded all of his body and mind. At first, he was too little to play on the South Side courts for real, so he would go with his dad to the playground and use anything he could as a hoop. He scored on baby swings, between the rungs of monkey bars, on milk crates.

That’s how it started. Now Wade has seen the highest reaches of American athletic success: All-Star, All-Star MVP, scoring champion, NBA champion, Finals MVP, Olympic gold medalist. Yet as intense as he may have been on the basketball court, in the six years since his retirement, he has presented a different face to the world—one that doesn’t fit with a certain narrow way of thinking about how a Black man should carry himself.

Wade and his wife, the actor Gabrielle Union, talk about their marriage as an equal partnership. For a long time, they insisted on splitting their finances 50–50. (Once, during an argument, Wade reminded Union that they were in “my house that I paid for.” She looked at her husband and replied, “You will never say that to me again.”) In 2020, Wade’s daughter Zaya came out as transgender, and he has very publicly supported her; last year, he won a Daytime Emmy as an executive producer on a short documentary about the fathers of trans kids. And those massive hands, which once authored ferocious dunks, are now immaculately manicured, the nails often painted. When Power said Wade had changed, this is what he meant.

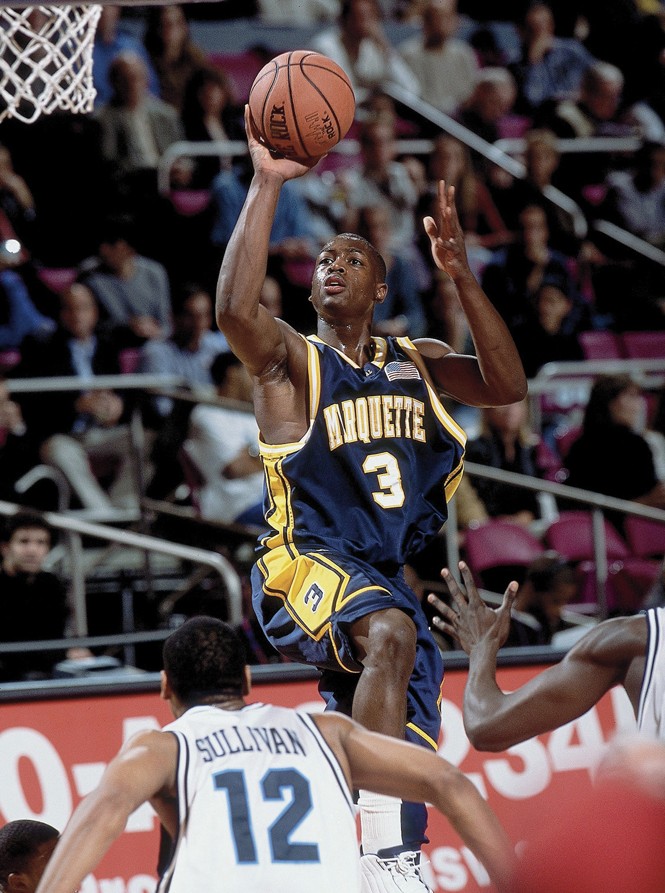

One night last year, I sat in a plush room at Fiserv Forum, in Milwaukee, and watched a woman empty the largest Chick-fil-A bag I’d ever seen onto a countertop: sandwiches, boxes of nuggets, packs of waffle fries. A nearby fridge was stocked with juices, sparkling water, and white wine. Fiserv is Marquette University’s home court. A group of school employees, sitting in leather chairs around the room, fidgeted while they waited for Dwyane Wade to arrive.

In 2003, Wade led Marquette to the Final Four, its first trip since the team had won its sole championship, in 1977. Wade’s team lost in the semifinals to the Kansas Jayhawks, but he left Marquette as a legend. In 2007, the school retired his jersey. Now, nearly two decades later, he was being honored for a $3 million donation, which would support a reading program, scholarships, and an expansion of the men’s-basketball facilities.

[From the October 2011 issue: The scandal of NCAA college sports]

Wade arrived with a small entourage (the Chick-fil-A was for them), and the room buzzed. He greeted me and leaned in for a shake; his hand eclipsed mine, almost reaching my wrist. He was dressed in black from neck to toe—black shirt, flared black pants, black socks, and black sneakers. On his head sat a cream cap with a black D in the center. Chin up, with perfect posture, he walked down a long hall toward the donor dining hall, where some of Marquette’s wealthiest alumni awaited him.

Wade, towering over everyone, was greeted by applause. He started his brief remarks with a joke about how he had finally given enough money to enter this room. Wade spoke passionately about his love for Marquette and how the school had changed his life. He didn’t, however, say much about what that life had been like before he got to college.

I imagined how strange it must be for Wade: all these white faces celebrating you as one of their own. No one else in that room had once been a skinny Black kid who lived where Wade lived and saw what he saw. He gave them a story they could comprehend—the truth, but not the truth.

I had struggled, at first, to get past such carefully constructed surfaces with Wade. In many respects, my own background is similar to his. He’s from the hood. I’m from the hood. We came of age around the same time, in places that many white people talk about like they’re alien worlds. It might sound strange, but I’ve found that Black people from poverty are often more cagey, more on guard, when talking with a Black writer from poverty. Maybe it’s because I know what’s beneath the success stories that get packaged for white audiences. Or I could be there with an ulterior motive, trying to prove that Wade has sold out—that he is “Hollywood” now. I’ve come to think of this kind of reluctance as the “Black Wall.”

Slowly, though, the wall started to come down, and I got a very different account of Wade’s life from the one he’d shared with the Marquette donors. When Wade was about 8 years old, he went to live with his father in Robbins, a small town on the outskirts of Chicago. Despite everything he’d gone through on the South Side, Wade didn’t want to leave; he was protective of his mother. His sister Tragil, then 12, had to trick him into leaving. She told her younger brother that he was just going to Robbins for a visit. He went for a ride, and that was that.

In Robbins, Wade lived with his father, stepmother, and four stepsiblings. Robbins was mostly Black, a place built by Black people who were tired of racial conflict in Chicago. One of Wade’s best friends in town, though, was white. “I’d never had a white friend before,” he told me. “It was different going over to his house after school some days and shit, you know what I mean? It was way different than my house. After school, there was food waiting for him, and the house was clean.” Wade commuted to a racially diverse school in Chicago, where he was quiet and shy. “My confidence was low because my shoes got holes in them,” he told me. When he wore white socks with his black shoes, he’d use a black marker to darken the sock where it showed through the holes.

Wade’s father was a standout baseball player in high school, and he’d dabbled in just about every sport except basketball. But after a stint in the Army, he came back to a Jordan-era, basketball-crazed Chicago and decided to be good at hoops. He dominated pickup ball around the city and its suburbs, and the boys in his house took after him. They played on a hoop their father had built in the driveway beside their house in Robbins. Dwyane Wade Sr. was a relentless coach. “He 6 foot 3, muscles, had a mean streak,” Wade told me. “Damn right, I’m listening to my dad. I had no choice. I was scared of my dad.”

“He brought that military background to everything we did,” Wade said. If Wade Sr. got it in his head that his son had to make a certain number of shots, he wouldn’t let it go. “We could be out there all night,” Wade said. “And I would cry through it; he didn’t care.” He often resented the pressure. “I’m talking about my shoulder hurting, my hand hurting, I’m hungry, I’m thirsty, whatever; he didn’t give a fuck. And so that was tough as a kid, because at that time, you want to do it, but you don’t want to do it that long. You don’t want to act like you’re training and really working at the game. You just want to play it.”

Tragil often visited the house in Robbins. She saw how hard her father pushed her brother. Wade Sr. made his son play against kids who were older and bigger than he was. In one game, playing as a fifth grader against eighth graders, Wade missed an easy shot. “Dwyane missed that left-hand layup; he couldn’t go left,” Tragil told me. “So Daddy made him stay out on the court until he got it right. He was crying and everything, but he learned to use that left hand.”

Growing up, Wade saw competing versions of what a man was supposed to be. He saw men putting their hands on women, men fighting each other, men drawing guns. He also saw his own father get up at five in the morning every day to take the train to make deliveries for a printing company. Wade Sr. demanded that the kids use ma’am and sir in the house. He made them clean the bathrooms and wash the dishes. Wade Sr. took pride in providing for his family. But Wade never recalls hearing him say the words I love you. “It was a lot of tough love as a Black man in America,” Wade told me. “At that time, wasn’t a lot of hugs going around for a lot of young boys in the community that I had.”

Even as Wade grew into his powers as a high-school player, his father continued to push him. “My dad was so intense that by the time Dwyane got in high school, he wasn’t allowed to come inside the gym,” Tragil said. “He was always trying to coach from the sidelines, so they ended up banning him from home games.”

Although Wade dreamed of playing college ball at Michigan, the school didn’t recruit him, because his ACT scores were too low. But Tom Crean—Marquette’s head coach, who was in his second year of transforming the program into a contender—had heard stories about the all-state shooting guard from Chicago, and decided to reach out. On June 25, 2000, just as the window to call high-school players officially opened, Crean contacted Wade at the home of his high-school sweetheart, Siohvaughn Funches. Funches’s mother told Wade to pick up the phone, and Crean sold him on becoming the cornerstone of the team he was building.

Wade wasn’t academically eligible to play as a freshman, and had to spend the year getting his grades and test scores up. That same year, his mother was incarcerated on drug charges related to crack. He wrote to her in secret, never telling anyone what was going on.

At first, Wade said, he used all the adversity as motivation. On the court and, for the first time, in the classroom, he tried to channel his anger and hurt: “He’s not this; he’s not that. He will never be this; he will never be that.” Wade drilled and studied. He spent hours overhauling his shot. He wasn’t allowed to travel with the team, but Crean sat him on the bench during home games and made him take notes. Wade was allowed to practice with the team, and it was clear that, even as a freshman, he was the best player out there.

“I was doing stuff that they couldn’t do,” Wade told me, “and I was like, Oh, wait, I’m different, you know what I mean?” His mother got clean in prison and was released just in time to see him play his first game, his sophomore year. Jolinda started her first ministry in prison, and years later Wade would buy her a church on the South Side.

Wade was 20 years old, a sophomore at Marquette, when he became a father himself. Funches gave birth to their son, Zaire, in 2002, and Wade and Funches married a few months later. Fatherhood overwhelmed Wade at first. Every bit of his financial aid went to diapers and baby food. “I was broke as hell in college, bro,” he told me. “I’m talking about broke broke.”

But Wade knew money was coming. The Miami Heat drafted him after his junior year. In that crowded class of prospects, each star had his own identity. LeBron James was the chosen one; Carmelo Anthony was the tough Baltimore kid who could get a bucket anywhere. Wade was the ruthless, hard-driving warrior. “I don’t give a fuck. I’m a savage,” he told me. “Especially if I felt like you crossed me or you said something to me I don’t like. I’m out here to win. I get dirty if we gotta get dirty.”

Before drafting Wade, the Heat had suffered two consecutive losing seasons, prompting the head coach, Pat Riley—who’d never had a single losing season before—to resign. But in Wade’s rookie season, the team advanced to the second round of the playoffs, where it faced the Indiana Pacers. Wade announced his arrival as a star by slashing through the lane, leaping over the Pacers’ center Jermaine O’Neal, and slamming the ball like he wanted to tear the rim off the backboard.

Though James is the most decorated player of his era, Wade was the first of his contemporaries to achieve team success in the NBA. In his second year, he made the NBA All-Star and All-NBA teams, and he and his new teammate Shaquille O’Neal led the Heat to the Eastern Conference Finals. The next season, in June 2006, with Riley back on the sidelines, Wade carried the Heat to the NBA Finals.

For me, the moment Wade became Wade was in that series, when the Heat played Dirk Nowitzki and the Dallas Mavericks. Miami went down by two games early, and nobody thought they would win the series. From the third game on, though, Wade seemed possessed. He hit mid-range jumpers; he got to the basket; he dunked on defenders’ heads; he made his free throws. Wade scored 157 points over the last four games, all Heat wins, and turned in a damn-near-perfect performance in the elimination game, playing with relentless energy on both sides of the ball. He brought Miami its first championship trophy and became one of the youngest NBA Finals MVPs ever. In just a few years, Wade had gone from an underrecruited high schooler to one of the highest-profile stars in the NBA.

When Wade had entered the league, baggy, untucked dress shirts and oversize suits were the style on draft night; on game days, players draped 5XL sweat suits and Mitchell & Ness throwback jerseys over their lanky frames. At the beginning of the 2005 season, then–NBA Commissioner David Stern implemented a dress code. It was unpopular and even deemed racist by many—a white commissioner forcing a league of predominantly Black millionaires to wear business casual. Wade, however, embraced the new restrictions. The next year, his tailored suits and taste for designer fashion landed him on Esquire’s best-dressed list.

Today, the NBA’s “tunnel walks” are like runways, with avant-garde couture, designer bags, and, yes, painted nails. But Wade recalls how the media jumped on him when he started to experiment with his fashion. “I remember in the early stages, if I wore a color, if I wore pink pants, they were talking about it like it was the worst thing ever,” he told me.

Wade wanted to be presentable, whether he was wearing sneakers and sweats or expensive sandals. But, like dancers, professional basketball players tend to have twisted and mangled feet, often crowned with discolored and bruised toenails. Wade had a solution for getting his feet together—he started to get pedicures, and had his toenails painted.

In 2007, Wade and Funches had another child, Zaya, but then separated that same year. Their divorce was a bitter tabloid saga, and their custody proceedings were among the longest in the history of Cook County. In 2011, Judge Renee G. Goldfarb granted Wade sole custody of both children, and they moved in with him. Zaire struggled with the change; he had been, he told me, “a momma’s boy,” and he worried that he was abandoning his mother. Basketball often kept Wade away from home, a fact that Goldfarb had considered. “But, to posit that he does not have the time to be a primary parent is incorrect,” she wrote. “He has the time if he makes the time.”

Dwyane, Zaire, and Zaya were all young, all still learning how to talk to one another. “I just was like, All right, I don’t know what the hell I’m doing,” Wade told me. He thought of his father’s emotional distance. He wanted to do things differently. “Me, I’m kissing you on the forehead,” Wade said. “I’m coming in there, I’m tucking you in at night. I’m coming off the road at three in the morning. I’m coming in to show you love.” He bought Zaire, then about 11, a blank notebook and told him to write down his feelings. Zaire told me, “I would leave it under his door, and then, whenever he would get back from a road trip, he would see it, open it, write his own thing, leave it back under my door.” Zaire, now 23, thinks the diary was crucial in helping him through his preteen years. “It was good,” he said, “ ’cause I never really knew how to express by talking.”

When Wade was in his mid-20s, his NBA career at its peak, he met Gabrielle Union, who’d starred in Bring It On, Bad Boys II, Daddy’s Little Girls, and Deliver Us From Eva, at a Super Bowl party. “She was different,” Wade said. Union was already an established presence in Hollywood, and he liked her confidence and independence. “She had her own bread, you know what I’m saying? She had her own swag.” During a break with Union, Wade had another son, Xavier, with a different woman. Eventually he and Union reconciled, and they were married in 2014; Union became a bonus parent to Zaire and Zaya. (Xavier is primarily raised by his mother.) That year, Wade was awarded full custody of his nephew Dahveon Morris. Four years later, Wade and Union welcomed a daughter, Kaavia James.

When Zaya first came out to Wade and Union as transgender, Wade was confounded. Nothing in his upbringing had prepared him for the experience of having a trans daughter. After Zaya was born, he had started planning for another generation of Wade basketball dominance. “When I had two boys, I was like, I got two chances at the NBA,” he said. Unlike Zaire, who dreamed of playing basketball, Zaya had never been interested in it. Sometimes, she’d come home, take off her school clothes, and put on a wig, heels, a dress. Back then, Wade admitted, he didn’t really know what being transgender meant.

Zaya, who turns 18 this year, told me she was afraid of what her father would think. “I was so scared,” she told me. “Everyone’s scared about coming out to their parents, and yeah, my parents are from Chicago. Chicago’s not the most, you know, I mean, you know … Like, in that moment, he had to make a choice: Do I stay in my beliefs from my childhood, or do I grow and expand and evolve in order to be a better dad for my kid? ”

It took Wade time to fully understand Zaya’s identity, and how to be her dad. He thought about how impossible her life would have been under the circumstances of his childhood. “I thank God all the time that I was able to be in a position in life that I was able to be in, but also that I was put in a position to be Zaya’s dad,” Wade told me. “If she grew up in my situation, forget about it. You’re either going to kill yourself, hurt yourself, or you’re going to keep that shit tucked in when you’re growing up like that; you’re not telling everybody.”

Wade and Union called their friends Magic and Cookie Johnson for advice. Their son, EJ, had come out to his family as gay when he was 17, and Wade remembered watching Magic talking about EJ in an interview with Ellen DeGeneres. “Well, I think it’s all about you not trying to decide what your daughter or son should be, or what you want them to become,” Magic had told DeGeneres. “It’s all about loving them, no matter who they are, what they decide to do.” He continued: “If you don’t support them, who’s going to support them and love them?”

Wade recalled thinking that Magic had navigated these interviews gracefully. “It was about EJ; it wasn’t about Magic,” he told me.

The Johnsons encouraged Wade and Union to relocate from Florida to California, where Zaya would have more community and a friendlier environment. The Wades decided to make the move, and the Johnsons helped them find a school that would be comfortable for their daughter.

After Zaya came out to the public, in 2020, Wade also went on The Ellen DeGeneres Show to express his support for her. Later, he talked about what it had felt like for him to see the fear in her face when she told him she was trans. “I had to go look myself in the mirror and ask myself: Why was my child scared, scared to tell me something about herself? ”

But, elsewhere within the family, the news did create turmoil. Shortly after Zaya came out publicly, her mother attempted to block her legal name and gender change until she turned 18. In court documents, Funches claimed that Wade was “positioned to profit from the minor child’s name and gender change with various companies through contacts and marketing opportunities.” She expressed her concern that Wade might have pressured Zaya into coming out, and said media attention would exacerbate that pressure. (Funches and her lawyers did not return requests for comment.)

It is true that as Wade’s daughter, Zaya might be one of the most visible young trans people in the world (she walked the runway during Paris Fashion Week in 2023, and landed the March 2025 cover of Seventeen magazine), but that prominence has also often made her a target. When she came out, the rapper Boosie BadAzz was incensed. “Like, don’t address him as a woman, dog,” he said in an Instagram video. “He 12 years old. He don’t, he’s not—he’s not up there yet.” The rapper Young Thug also weighed in on Twitter: “All I wanna say to dwade son is ‘GOD DONT MAKE MISTAKES’ but hey live your true self.”

Wade does his best to tune out the bullshit, but he can’t stop his kids from seeing every slight or attack. Yet Zaya says that he’s made their home a sanctuary for her, and in doing so has given her the comfort to succeed. “If a father wants some advice,” she told me, “it’s all about making sure your kids feel loved and they feel accepted and they’re protected and they’re safe.” For Zaya, this is a basic tenet of fatherhood, no matter who your children are, or what happens in their life.

The challenges of protecting a world-famous trans daughter aside, Wade is trying to navigate the basic father-teen dynamics. One day, he decided to surprise Zaya by picking her up at school. “I was coming from a meeting and I was dressed rather nice and I was in my Maybach,” he said. Zaya was outside with all of her friends; Wade was blasting music with his windows down and got out of the car. “I was just hanging on the car, like, ‘Hey, Zaya.’ ” She and her friends saw him and laughed. When she got in the car, Wade said, “I was like, ‘Did I look cool?’ She’s like, ‘Yeah, Dad, you looked cool.’ ”

Once, long after Wade had left 59th and South Prairie, his mother told him a story. Back in those early years, when she was dealing with drug addiction, Wade’s father would drive to her neighborhood after work, looking for her. When he found her out on the streets, he’d sit with her for a bit and ask her if she needed anything before he went home. As bad as their relationship was, she was his kids’ mother, and he wanted to make sure she was okay.

It took Wade a while to fully appreciate his father, to understand why he’d been the kind of parent he was. Wade Sr. drilled into his son the competitive drive necessary to become an elite athlete, and his ex-Army toughness taught Wade about respect. “When I got coaches—when I got high-school coaches, eventually college coaches, NBA coaches—I already had that respect built in, and it was built in from my dad being my first coach.”

In 2023, when Wade was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, he gave a speech thanking his teammates, his coaches, Marquette, his family. Finally, he asked his father to stand up. “The hard work I put in is because I didn’t want to let you down,” he said. “Those countless hours in the backyard where we would compete against each other like strangers—it built me to last.” In the audience, Wade Sr. nodded slowly, his hands clasped. “I admired you as a kid,” Wade said. “I admire you now.” Then he invited his dad to join him onstage. “This one is for my father,” he said. “I love you, and I’m thankful for you.” They pulled each other into a hug. “I love you too, man,” Wade Sr. said.

A few months after the Hall of Fame ceremony, I spoke with Wade Sr. over Zoom. He still seemed to be reeling from that speech. “I wasn’t prepared for it,” he said. “That was an incredible, surreal moment.” We talked about how, when his son was growing up, priorities seemed clear-cut: “Staying away from the gangs, which is, you know, on the next block, and then, you know, the next block, and the next block.” For Wade Sr., the primary goal was staying alive. He tried to teach discipline above all. “I’ve always wanted to be a strong father,” he told me.

But there is plenty about Wade’s life that his father can’t quite grasp. Wade Sr. knows that his son goes to therapy, which he still can’t wrap his mind around. “I’m not going to talk to nobody about Dwyane; that’s who I am,” he said, referring to himself. “If I can’t understand me, how I’mma expect somebody else to understand me? So I try to keep it in-house.” But some men are just built differently, Wade Sr. tells himself. With his son, he said, “I’ve always tried to instill: Be better than me. I really think that, in a way, he took his own path.”

There’s still no shortage of old-school discipline and hardness about Wade. In January, he publicly revealed that he’d had surgery to remove a cancerous tumor from his kidney in December 2023. “I think it was the first time that my family, my dad, my kids, they saw me weak,” Wade said on his podcast. “That moment was probably the weakest point I’ve ever felt in my life.” He had carried that weakness privately, never mentioning it to me over the course of our many conversations, or to anyone outside his family.

I thought back to the barbershop, where so many people had opinions on how Wade went about his career and his life. Everyone in the shop knew how they would handle marriage, fatherhood, and a post-NBA career if they were in Wade’s shoes. They would be better Dwyane Wades than Dwyane Wade.

Just a couple of weeks after Wade had that secret surgery, we loaded into a black SUV and drove to the South Side.

We were going to Wade’s childhood home, where he’d lived with his mother. The higher the street number, the more abandoned the blocks seemed to be. And I don’t mean abandoned by the people—they were out, even though it was freezing. I mean abandoned by the city. Well-manicured businesses and beautiful homes on clean, trash-free streets slowly turned into fast-food chains, and then run-down local storefronts, and then not much of anything—a different Chicago.

I was riding in the back seat with Dwyane and Tragil. Both were in a reflective mood. Tragil recalled how Dwyane, at age 4, had figured out how to cross a busy street and walk to a corner store called Miss Pearl’s so he could buy Little Debbies.

“Look to the left,” Tragil said. “You see that garage?”

“Yooooo, the garage,” Dwyane said.

“That was Miss Pearl’s,” they said, nearly in unison, laughing.

The darker memories came, too. Dwyane talked about the fights he got into with different boys in the neighborhood; the police raids where cops busted into their home, arresting every adult inside. As they passed another building, Dwyane motioned out the window. “This is where I used to watch my mom—and, like, she ain’t know I used to see her; she used to be shooting up.”

Dwyane rested his chin on his hand.

“We coulda stayed here, and we coulda struggled,” Tragil said.

Dwyane nodded. “This coulda just been our life.”

We arrived at 5901 South Prairie Avenue, a big three-story building that sat on a corner. Its black gate was wide open.

“They didn’t have this gate when we lived here,” Tragil said. “Remember how the cops always tripped on that top step because it was never fixed?”

“Remember the time we were running from the cops, and you fell?” Dwyane said. “I looked back and you was gone.”

We jumped out of the SUV. Tragil pointed to a spot where there’d once been a bush in which dealers used to hide drugs. Dwyane walked around the outside of the building, taking photos. Brother and sister kept sharing flashbacks, finishing each other’s stories as their eyes welled. They paused, wiped their tears, and continued to bask in nostalgia. We walked through the gate up onto the porch. Even though the step had been fixed, somehow I still tripped on it, just as the cops had.

Wade showed me a scar on his head, and gestured toward a railing he’d once fallen from. “I didn’t go to the hospital,” he laughed. “I was told to put some water on it, maybe a little alcohol, even though I had a concussion.”

I tried the building’s front door, and to our surprise, it was open, so we went in. Like excited kids, we ran up and down the central staircase, trying doors on each landing, but they were all locked. On the middle floor, where Wade’s cousins used to live, a Ring camera had been installed. Wade looked directly into it and said hello multiple times, pressing the button, but no one answered. After trying every other door in the building, we went back outside.

Tragil looked up the rent for one of the building’s apartments: $1,400 a month. “They tryin’ to gentrify,” Wade said.

We got back in the car. In those South Side days, Wade said, “I just felt out of control of my life.” He reminisced about how he used to sit on the building’s porch, watching the rain. “I saw the same things I just seen. Like, it doesn’t look that different,” he said. “But my thoughts were different. I was, you know, thinking of a better life.” He wouldn’t relive those years for anything. But he believes they taught him patience, how to work hard and wait. Now he’s trying to teach his kids the same thing. It’s not easy: “They don’t have it,” he said. “Like, my son wanted to be in the NBA at 18. And he expected that. He has no patience.”

Years ago, he’d taken Zaire to see 5901 South Prairie, though they hadn’t gone inside; they’d taken a photo on the front steps. Dwyane wondered aloud how his younger children—whose lives couldn’t be further away from this place—might react to seeing it now. “I would love for them to walk through it.”

Wade gazed out the window at the South Side as we rode back to the other side of town, past the empty lots and the run-down buildings. “That’s what the American dream is, though,” I said. “You bust your ass. And then your kids get to have a different experience.”

Wade smiled wide and nodded. “Yeah,” he said.

This article appears in the May 2025 print edition with the headline “The Making of Dwyane Wade.”