Berlinale Dispatch: Size Doesn’t Matter

Mickey 17 (Bong Joon-ho, 2025).The Berlin International Film Festival is shrinking. Not in the number of films shown—in fact, like Toronto and Rotterdam, it would greatly benefit from judicious slimming—but in the grandeur of its selection. The “big” films at Berlinale—in terms of stars, major auteurs, visionary scope, fervid anticipation—seem fewer each year, as most vie, for promotional reasons, to premiere at Cannes or Venice.This is perfectly fine. Smaller movies, those of more limited means and contained ambitions, stand to do well as audiences and investment continue to be drawn away to other media. As long as platforms and venues remain to bring smaller films to audiences, there is nothing preventing them from being as beautiful or as important as the big ones—if not moreso, since they are less fettered by commercial pressures. This year’s Berlinale rewarded audiences with quite a strong program of modest films, if they knew where to look. The one grand statement of cinema it did spotlight, Bong Joon-ho’s lumbering and politically pandering sci-fi Mickey 17 (all films 2025, unless noted), underscored that their absence was not necessarily a bad thing.Considering that Hollywood is still reeling from cataclysmic wildfires on the heels of recent labor strikes and pandemic disruptions, it’s a wonder that something like Mickey 17 even premiered this year, let alone that it did so at Berlin instead of at Cannes or Venice. Meanwhile, Strike Germany continues, an international call to withhold labor and attendance from the nation’s arts institutions to protest the way they have suppressed expressions of solidarity with Palestine, though its effect appeared muted; several artists and writers pulled work from the festival or declined to to attend, but public ticket sales were slightly higher than in 2024. The Berlinale has a new director, Tricia Tuttle, who comes from the BFI London Film Festival, and her inaugural edition didn’t feel markedly different from the last five years under Carlo Chatrian and Mariette Rissenbeek. The scale of films was similar to the last several editions, with potent, home-brewed films in competition from past winners Radu Jude (whose Kontinental ’25 was awarded best screenplay) and Hong Sang-soo. The Encounters section, a competitive sidebar of formally adventurous movies that might otherwise have been shown in another of the festival’s sections, is no more. It is replaced by Perspectives, a competitive sidebar of feature-length debuts that might otherwise have been shown in another of the festival’s sections. It joins Rotterdam’s Tiger competition, Toronto’s Debuts, and Cannes’s Critics’ Week, among others, in hoping that there are enough compelling debutants each year to fill all of these programs.Such hope seemed justified by Perspectives selection Mad Bills to Pay (or Destiny, dile que no soy malo), whose directorial force signals Joel Alfonso Vargas as a major talent to follow. It is a straightforwardly social realist portrait of Rico (Juan Collado), a Dominican American nineteen-year-old living in the Bronx with his mother and younger sister and selling boozy drinks on nearby beaches. When his younger girlfriend (Destiny Checo) learns she’s pregnant and has to move in, Rico treats her kindly at first, but the challenge of leaping from carefree teenagehood to responsible adulthood soon begins to show. An archetypal scenario of young masculinity drawn into self-doubt when confronted with the practical and emotional needs of others, the film may be conventional in its drama, but it is exceptional in its deep-space immersion in its characters’ lives and world. Vargas’s imagery is unshowy yet dazzling in its detail, from a pizzeria composed as a cluttered collage of menu, drinks, and slices to an angled nighttime tableau in which Rico drunkenly antagonizes a man washing his car near the elevated Freeman Street subway station. The film allows our eyes to rove around the frame in that old school Bazinian sense, free to explore its depths and richness. The Bronx of Mad Bills to Pay is lived in and living, and all the more thrilling to see because the borough is so rarely filmed. Along with its affectingly no-nonsense acting, the film is a showcase for a filmmaker whose observations bring the world to the image.Top: Mad Bills to Pay (or Destiny, dile que no soy malo) (Joel Alfonso Vargas, 2025). Bottom: Paul (Denis Côté, 2025).Denis Côté’s Paul forges a different path by looking at the person to understand a wider world, that of socially maladroit online content creators. The documentary premiered in the Panorama section, a broadly socially-themed program that proclaims its audience-friendliness and is known for favoring nonfiction and queer cinema. “Cleaning Simp Paul,” as the film’s protagonist is called, is an isolated young man in Montreal who deals with anxiety and body shame by cleaning houses for dominatrixes, a form of submission Paul has made part of his social-media persona.

Mickey 17 (Bong Joon-ho, 2025).

The Berlin International Film Festival is shrinking. Not in the number of films shown—in fact, like Toronto and Rotterdam, it would greatly benefit from judicious slimming—but in the grandeur of its selection. The “big” films at Berlinale—in terms of stars, major auteurs, visionary scope, fervid anticipation—seem fewer each year, as most vie, for promotional reasons, to premiere at Cannes or Venice.

This is perfectly fine. Smaller movies, those of more limited means and contained ambitions, stand to do well as audiences and investment continue to be drawn away to other media. As long as platforms and venues remain to bring smaller films to audiences, there is nothing preventing them from being as beautiful or as important as the big ones—if not moreso, since they are less fettered by commercial pressures. This year’s Berlinale rewarded audiences with quite a strong program of modest films, if they knew where to look. The one grand statement of cinema it did spotlight, Bong Joon-ho’s lumbering and politically pandering sci-fi Mickey 17 (all films 2025, unless noted), underscored that their absence was not necessarily a bad thing.

Considering that Hollywood is still reeling from cataclysmic wildfires on the heels of recent labor strikes and pandemic disruptions, it’s a wonder that something like Mickey 17 even premiered this year, let alone that it did so at Berlin instead of at Cannes or Venice. Meanwhile, Strike Germany continues, an international call to withhold labor and attendance from the nation’s arts institutions to protest the way they have suppressed expressions of solidarity with Palestine, though its effect appeared muted; several artists and writers pulled work from the festival or declined to to attend, but public ticket sales were slightly higher than in 2024. The Berlinale has a new director, Tricia Tuttle, who comes from the BFI London Film Festival, and her inaugural edition didn’t feel markedly different from the last five years under Carlo Chatrian and Mariette Rissenbeek. The scale of films was similar to the last several editions, with potent, home-brewed films in competition from past winners Radu Jude (whose Kontinental ’25 was awarded best screenplay) and Hong Sang-soo. The Encounters section, a competitive sidebar of formally adventurous movies that might otherwise have been shown in another of the festival’s sections, is no more. It is replaced by Perspectives, a competitive sidebar of feature-length debuts that might otherwise have been shown in another of the festival’s sections. It joins Rotterdam’s Tiger competition, Toronto’s Debuts, and Cannes’s Critics’ Week, among others, in hoping that there are enough compelling debutants each year to fill all of these programs.

Such hope seemed justified by Perspectives selection Mad Bills to Pay (or Destiny, dile que no soy malo), whose directorial force signals Joel Alfonso Vargas as a major talent to follow. It is a straightforwardly social realist portrait of Rico (Juan Collado), a Dominican American nineteen-year-old living in the Bronx with his mother and younger sister and selling boozy drinks on nearby beaches. When his younger girlfriend (Destiny Checo) learns she’s pregnant and has to move in, Rico treats her kindly at first, but the challenge of leaping from carefree teenagehood to responsible adulthood soon begins to show. An archetypal scenario of young masculinity drawn into self-doubt when confronted with the practical and emotional needs of others, the film may be conventional in its drama, but it is exceptional in its deep-space immersion in its characters’ lives and world. Vargas’s imagery is unshowy yet dazzling in its detail, from a pizzeria composed as a cluttered collage of menu, drinks, and slices to an angled nighttime tableau in which Rico drunkenly antagonizes a man washing his car near the elevated Freeman Street subway station. The film allows our eyes to rove around the frame in that old school Bazinian sense, free to explore its depths and richness. The Bronx of Mad Bills to Pay is lived in and living, and all the more thrilling to see because the borough is so rarely filmed. Along with its affectingly no-nonsense acting, the film is a showcase for a filmmaker whose observations bring the world to the image.

Top: Mad Bills to Pay (or Destiny, dile que no soy malo) (Joel Alfonso Vargas, 2025). Bottom: Paul (Denis Côté, 2025).

Denis Côté’s Paul forges a different path by looking at the person to understand a wider world, that of socially maladroit online content creators. The documentary premiered in the Panorama section, a broadly socially-themed program that proclaims its audience-friendliness and is known for favoring nonfiction and queer cinema. “Cleaning Simp Paul,” as the film’s protagonist is called, is an isolated young man in Montreal who deals with anxiety and body shame by cleaning houses for dominatrixes, a form of submission Paul has made part of his social-media persona. The film takes a contemplative step back from the high-energy aspirational self-poraiture of Paul’s daily videos. Its patient, nonjudgmental 16mm photography finds a degree of specificity and interiority in Paul that is obfuscated by his heavily edited and narrated videos, lending Paul’s gentle, withdrawn face a sympathetic ambiguity. While the portrait is petite, the interest and respect with which Côté treats Paul makes for an analog ode to the struggles of self-expression for so many online creators.

The independently programmed Forum section, now in its second year under Barbara Wurm’s leadership, proved to host the most consistently arresting experiences at the festival. It takes considerable courage, for example, to curate, as well as to watch, Kang Mi-ja’s devastatingly unblinking Spring Night, a film that tells of bodily illness and spiritual communion with austere focus, made on next to no budget. At cinema’s most depressing wedding after-party, a man (Kim Seol-jin) facing deteriorating arthritis and financial failure encounters a woman (Han Ye-ri ) in the depths of alcoholism and loneliness. They listen to one another’s sorrows, he carries her home at the end of the night while she drunkenly murmurs poetry; they see each other again and repeat the experience. Through presence and earnest commiseration—simple but powerful acts—an intuitive and compassionate bond is formed between two damaged souls. Unlike Paul, where the focus is on the succor and creativity of radical self-care, Spring Night is about the blessing of finding someone with whom to share despondency. Their kind of love is not a cure for life’s afflictions, but a merciful balm.

Top: Spring Night (Kang Mi-ja, 2025). Bottom: Houses (Veronica Nicole Tetelbaum, 2025).

Veronica Nicole Tetelbaum’s Houses is close kin to Spring Night in its portrait of a forlorn life tended to with compassion. Sasha (Yael Eisenberg) is living out of their car while on a personal quest to visit the homes of their youth in the Israeli city of Safed. Why their family moved so often is ambiguously ascribed to the social alienation of having immigrated from the Soviet Union. Some of the houses are now abandoned and others variously inhabited, giving the ruminative tour a haunted quality. The black-and-white photography is interrupted by color home-video footage of Sasha’s troubled memories, and we find that the present is inhospitable to their nonbinary gender. With emotionally charged cinematography that wouldn’t look out of place in the 1920s of F. W. Murnau and John Ford, and an empathetic narrative of an outsider reminiscent of the films of Kelly Reichardt, Houses is a lean but piercing mood piece of dislocation. Tetelbaum’s poetic and heartfelt debut confronts the past while looking for a safe haven for the future.

The most deceptively charming film in the Forum, Želimir Žilnik’s wily 80 Plus, also visits a house that brings together two moments in time. With a cast of mostly elderly nonprofessionals (Žilnik, who won the Golden Bear in 1969 for Early Works, is 82 himself), the exceptionally convincing faux-documentary tells the story of Steven (Milan Kovačević), an aging musician returning to his native country of Serbia to repossess his family estate. Once confiscated by the socialist government, the house is clearly a metonym for the recent history of Yugoslavia. His trip home mixes nostalgic reunions and more contentious reconnections with the family he abandoned in the 1960s to travel and live in Western Europe, including his ex-wife, a greedy son-in-law, and a dispossessed granddaughter. Steven returns as a good-natured visitor, grateful for having led a fulfilling life abroad and full of benign positivity. The film follows his lead, taking the tone of endearing old folks recollecting old times. Yet with these quaint figures and tropes, Žilnik mobilizes a story covering the entire twentieth century of Serbian history, starting with dominion by landed gentry, passing through the trauma of the Second World War, the reclamations of socialism, and the fallout of capitalist transition. The contentious restitution of the estate centers not only a family’s tensions but that of a society: a fight over legacy, who is owed what, and whether to restore, tear down, or reimagine. In this disarmingly basic yet exceedingly sophisticated film, the message rings clear: any story of this generation is the story of the fight and fate of a country.

Top: 80 Plus (Želimir Žilnik, 2025). Bottom: The Ice Tower (Lucile Hadžihalilović, 2025).

The main competition is where one expects to find sweeping grandeur, but this year there were only two notable competitors of high style. The Ice Tower, which won an award for outstanding artistic contribution, continues director Lucile Hadžihalilović’s cinematic fairy tales of female transformation after the Cronenbergian English-language fable Earwig (2021), but in a leaner, more abstractly atmospheric style. Set among snow-muted mountains that lend the film a beautifully concussed sense of time and space, it follows a teenaged Jeanne (Clara Pacini) as she runs away from her foster home and finds refuge in what turns out to be an alpine movie studio. Nominally taking place in the 1970s, The Ice Tower in fact exists in that uncanny Lynchian space between the conventional world and that of a dream. In such a place, the fairy tale of an ice queen that Jeanne reads to a foster child is also the movie being made, and Jeanne’s longing to leave home and grow up becomes intertwined with her enthrallment with the aloof, impressive figure of the ice queen in the story and the diva actress (Marion Cotillard) playing her in the film. Along with its vaporous evocation of a vacant town lit by streetlights, bare backlot hallways and velvety dressing rooms, real snow and movie snow falling interchangeably, the film conjures and sustains a sense of otherworldly longing and tantalizing mystery. Without fetishizing the act of moviemaking, Hadžihalilović merges it into Jeanne’s fable, playing with the projection of fantasy and its manifestation. While The Ice Tower overextends itself beyond its worn-smooth tropes, the film, anchored by Pacini’s sensitive performance of yearning, achieves something primeval in the confluence of fables and movies, understanding that the stories we are told in turn inspire us to make, remake, and unmake the world in harmony with our desires.

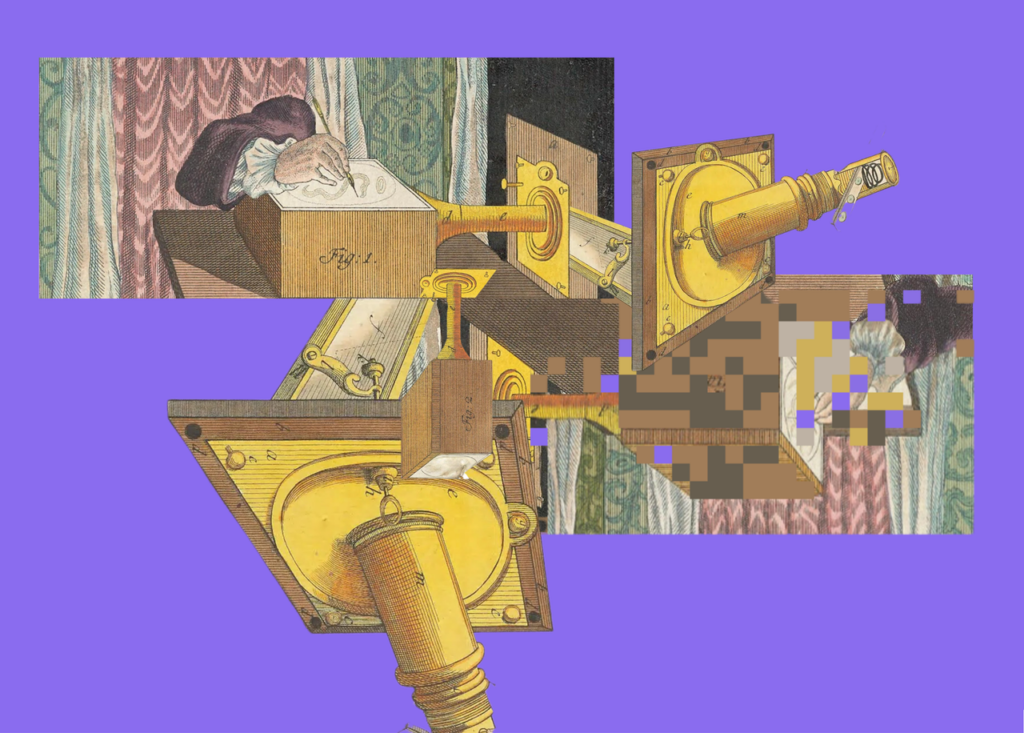

Reflection in a Dead Diamond (Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani, 2025).

Moviemaking as a liminal space between imagination and actualization is also what drives genre-infautated duo Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani and Reflection in a Dead Diamond, their latest and best film. Cattet and Forzani obsess over artisanal craft and film history to create inventive, precariously arch revivals of 1960s and 1970s European genres like the Italian giallo (The Strange Color of Your Body’s Tears, 2013) and the French policier (Let the Corposes Tan, 2017). Their approach is to create the ultimate pastiche of these pulp traditions, giddy reductions of myriad movies down to a fevered montage of emblematic characters, objects, tropes, and techniques—all the good bits of material and imagery, unencumbered by psychology and melodrama. Imagine if Josef von Sternberg’s movies were only close-ups of Marlene Dietrich, or if Michael Bay’s were simply one explosion after another. This is where the mainstream and the avant-grade meet, isolating and purifying the contents and attributes of commercial cinema into its most potent distillate. All filmmakers should take note of Cattet and Forzani, for they see every element of their films—each image, action, and sound—as an opportunity for ingenuity that can inspire gasps of delight and shock. The result is a superabundance that can sometimes be too much of a good thing, overwhelming and numbing one’s cinematic receptors.

Their latest gains both depth and a greater motivation for their cinema fever by framing its story as the fragmented and confused memories of an aged spy (Fabio Testi)—an ingenious premise. On a beachside holiday, the diamond nipple piercing of a bathing woman inspires a bloody, psychedelic trip through the man’s glamorous, ruthless prime as a swinging secret agent (Yannick Renier). Chased through these visions is the figure of Serpentik, a leather-clad vixen of enigmatic identity, both a rival and an object of impossible desire. Masks cover other masks, identities blur, and reality goes kaleidoscopic. Pulling from James Bond films as much as the schlockier delights of fumetti neri pictures like Danger: Diabolik (1968), the film adds another layer by having the spy-versus-spy havoc inspire a movie series, further muddling glory days with cinematic fancy in the old man’s mind (and our own). Like Mulholland Drive (2001),the film takes a subjective plunge into the fractured mirror-maze allure of silver-screen iconography and nostalgia, indulging the fantasy while revealing its depravities: Dead Diamond is as much about the nihilistic futility of a life of violence (if this is an old killer’s recollections) as it is about the empty propagandistic fantasy of gentleman Bond and his ilk (if this is a movie star’s memory). The film has its cake and eats it too, finding in movies and their making that intoxicated ecstasy and grotesque excess go hand in hand. This, of course, is hardly limited to spy capers. Looking for a movie that is big and splashy at the Berlinale, where art is supposed to be at the center, when in fact the needs of the industry are as much at play and on show, suggests that such knowing hypocrisy of combining relish with ruthlessness might just be at the heart of big festival expectations.

Berlinale Top 10:

01 Reflections in a Dead Diamond (Cattet/Forzani) 02 80 Plus (Žilnik) 03 Mad Bills to Pay (or Destiny, dile que no soy malo) (Vargas) 04 The Ice Tower (Hadžihalilović) 05 Houses (Tetelbaum) 06 Spring Night (Kang) 07 What Does That Nature Say About You? (Hong) 08 Paul (Côté) 09 Dreams in Nightmares (Ford) 10 Kontinental ’25 (Jude)