What did IndyCar teams learn from last week's Open Test?

Perfect weather made last week’s Indy Open Test a pleasure to experience for those who were in attendance. The Wednesday-Thursday (...)

Perfect weather made last week’s Indy Open Test a pleasure to experience for those who were in attendance. The Wednesday-Thursday outing was run under clear blue skies most of the time, and with a minimum of wind and humidity.

As idyllic as the weather happened to be, the 12 teams and 34 drivers in attendance also knew the ambient conditions were unlikely to be repeated in the coming weeks when official practice gets underway for the Indianapolis 500, which made the value of some of what they learned a bit questionable since running in hotter, colder, or windier settings in May will require different chassis and aerodynamic setups than those used and refined at the test.

But a few trends stood out that could shape how the May 25th race will be settled after 500 miles, with the first being found with Honda’s apparent return to competitive speeds around the 2.5-mile oval. The same was true for its leading team at Chip Ganassi Racing.

In 2024, CGR and Honda went backwards at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway as Team Penske and Chevrolet dominated the event in qualifying and on race day, and while both remain as possibilities for this year’s race, the indicators from the Indy Open Test suggest another hardcore fight between IndyCar’s top two teams and its dueling auto manufacturers is on the way.

Ganassi’s Alex Palou and Scott Dixon were quick throughout the test in sessions where drafting or qualifying simulations were run, and in another encouraging note that leans towards a more balanced battle, CGR’s technical affiliates at Meyer Shank Racing were also fast.

For qualifying, the best insights are drawn from the test’s no-tow report, which had a nearly equal top 10 comprised of six Hondas and four Chevys, with Honda-powered Takuma Sato from Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing and Kyle Kirkwood from Andretti Global taking first and second, respectively, followed by Penske’s Scott McLaughlin in third.

Those all came during qualifying simulations, with Sato’s 232.565mph lap being best of all no-tows, which should ease some of the fears surrounding the new and heavy hybrid engine package having a dire affect on average qualifying speeds. Nobody is expecting track records to be set with the net 100-pound gain caused by the energy recovery systems, but at least with high-boost qualifying turbocharger settings, four-lap average speeds should fall in a familiar range.

Another encouraging trend was the competitive flexes by Andretti and RLL, with RLL being the team that turned the most heads after its drivers ranked first with Sato, fourth with rookie Louis Foster, 10th with Graham Rahal, and 17th with Devlin DeFrancesco on the no-tow list. If the form holds, qualifying should be a breeze.

Chevy has been a beast at Indy in recent years, and there’s no reason to believe that will change. Strengthened resistance from Honda certainly stands out as something to track, and in turn, more of its teams should be in the competitive mix.

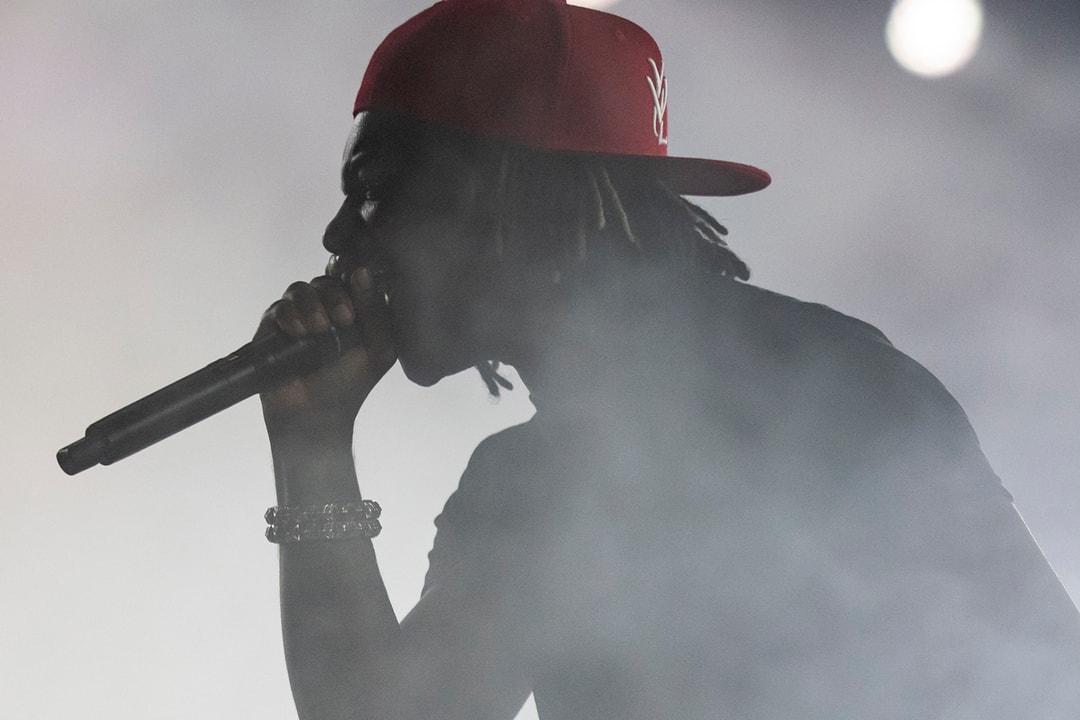

Sato didn’t need a tow to get speed out of the RLL Honda, although many other drivers’ qualifying simulation runs were derailed by traffic. Joe Skibinski/IMS Photo

Sato didn’t need a tow to get speed out of the RLL Honda, although many other drivers’ qualifying simulation runs were derailed by traffic. Joe Skibinski/IMS Photo

“It definitely looked like we were a lot more in the ballpark than last year, and there was a sigh of relief, rather than, ‘Oh boy, we’re in trouble,” CGR director of performance Chris Simmons told RACER. “I don’t want to read too much into an open test without knowing who was running what power level, but we were pretty happy with the test list we got through, and the performance we had and the handling and speed of the cars. We’re a lot better place than we were at this time last year.

“There weren’t many people who got clean four-lap qualifying sims, so there wasn’t a totally clear picture for everyone there. Palou got zero. He tried three times and got traffic on the first or second lap each time, but it looked better for our (Honda) side. I know they’ve put in a lot of work for this race. We got to do some race running and our guys were pretty happy with what they had.”

With the kinder ambient conditions in mind, most drivers said they did not experience worsened tire wear due to the added hybrid weight in longer race-simulation stints. Andretti’s Kirkwood was among those who said the first true read on hybrid-related tire degradation will have to wait until May.

“It was just too nice, to be honest, to see what it will do,” he said. “The track never got super hot or super greasy, so maybe there was some increased deg, but nothing that really stood out while you were sitting there in a pack, going after it lap after lap.”

Drivers spent plenty of time running together in the afternoon sessions, which replicated race-day running. Owing to Simmons’ note about so few drivers getting truly clean qualifying simulation runs, teams did not learn as much as they wanted about using the 50-60hp available from the ERS units during those outings.

“I don’t know if anybody came away feeling like they’re confident in the best way to use it in qualifying,” he said. “We saw a lot of people deploying on their third laps, which is traditionally when you start to see deg come in and RPMs come down, so it’s pretty obvious to use (hybrid power) there to bring that back up a touch to complete the run and get back some of what you naturally lose. But there were other strategies to try, too.”

Under a new allowance from IndyCar, teams were given the option to continue using the full-power deployment solution they’re familiar with or, in a new twist for the Speedway, to select a smaller but sustained hit of power. A short burst of maximum hybrid boost or a longer contribution of a lesser helping of horsepower… which one was better?

Teams who tried both aren’t telling, but it’s bound to be an area of greater exploration next month.

“You have to pick your power level and then stick with it,” Simmons said. “Whatever that (lower) power level is, you can’t switch back to full power if you don’t like it, so there’s a lot to try and a lot for teams to decide what they think is the best approach to take.”

![Kyoto Hotel Refuses To Check In Israeli Tourist Without ‘War Crimes Declaration’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/war-crimes-declaration.jpeg?#)

![New Best Ever Bonus for Capital One Venture Card Available Through Referrals [YMMV]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/6cbab7b59a0f3413c2a8f73cf771602a.png?#)