Want to Use Fewer Eggs? Cook Like It’s World War II.

Old wartime cookbooks are full of recipes that offer egg substitutes. How good they are is another question. I only recently realized just how much I rely on eggs in my diet. This was easy to ignore when the price for a dozen was cheap enough that I could splurge on the certified-humane, free-range kind without feeling like I’d spent my entire paycheck. Also, eggs are just easy: How many times a week have I made a last-minute lunch by frying an omelette or putting a fried egg on top of leftover rice faster than I could prepare anything else in my kitchen? In terms of both cost and versatility, eggs feel like the ultimate convenience food. But yes, when a dozen started costing double digits, I realized I may have built myself a problematic habit. The eggs had taken hold of me, and I resented their absence. This felt silly. For most of human history, people did not eat the amount of eggs I do year round. Even during times when eggs were plentiful, humans sometimes had to restrict their usage. So what better place to look to than to times of war, specifically World War I and World War II, to see how people on the home front substituted and rationed their way around eggs. According to food historian Sarah Lohman, author of Endangered Eating: America’s Vanishing Foods, there are two main reasons a food would have been rationed during war. One, “foods that were shelf stable and portable were rationed so that they could be sent to feed military operations,” she says. So while items like fresh cheese were difficult to ship, hard cheese and dried fruit were rationed to feed the troops. The other reason for rationing came down to a disruption in lines of production, whether because the men farming the wheat for flour were now in the army, or because of conflict somewhere along the production and importing routes. Mirrorpix via Getty Images Eggs were heavily rationed in the UK during WWII. A quarter of the country’s eggs were shipped over from America during that time, and often arrived spoiled. Adults were limited to one egg a week, though exceptions were made for children, pregnant people, and vegetarians. In the U.S., eggs were never rationed that heavily, though there were various wartime campaigns to ensure people weren’t wasting food. This poster from WWI encouraged Americans to keep hens and make money by selling the eggs during laying season, instead of selling the birds for meat. During WWII, The Victory Cookbook: Wartime Edition noted that eggs would likely face only “seasonable fluctuations,” and recommended them as a great source of protein and vitamins when meats were unavailable. In the UK, packets of powdered eggs were also made available, although the taste absolutely left something to be desired. According to Lohman, the trick was to use them to supplement other baked goods. “You can put some dried eggs in gingerbread and be fine,” she says, and get a bit of added protein. Wartime cookbooks also had tips for avoiding egg usage during economic depression. Lohman’s copy of The Victory Cookbook said that in butter cake recipes, “the number [of eggs] can be reduced to 2 ½ teaspoon baking powder for each egg omitted.” Many other wartime cake recipes, like this one from the BBC, use baking powder and vinegar to mimic the rise that eggs provide in baked goods. And the 1938 Davis Master Pattern Baking Formulas has a section on “one-egg cakes.” How good these recipes are is another question, however. Most war cakes were overly crumbly or dense, not exactly a mimic of an airy yellow birthday cake. And other substitutions were slightly questionable, like those of margarine and water in place of eggs. I decided I should give one a shot. I’d made eggless fruit cakes before, so I chose something for which it feels like excluding egg might be a real stretch—a recipe for eggless mayonnaise from a pamphlet for “tempting, thrifty wartime meals,” published in 1942 by PET evaporated milk, that illustrated all the ways its product could be used to stretch meat and substitute for other ingredients. The eggless mayonnaise recipe asks you to stir together three tablespoons of evaporated milk with oil, lemon juice, and the barest of seasonings. At first it looked like mealy salad dressing, and after a blitz in the blender it was still liquid instead of a spreadable condiment. It tasted like crayons. “I wonder if this panic is more symbolic, that it’s something that we’re used to being cheap and plentiful, and when it’s not, it almost takes away a little bit of our American identity,” Lohman says of the egg price crisis. Though forging an identity around the availability of eggs is still a relatively new conceit: Eggs are a seasonal food, and before our time of (relative) abundance, people either utilized preservation methods like pickling or waterglass storage, or just waited until it was laying season again and eggs became cheap. And now, we enjoy certain advantages earlier gene

Old wartime cookbooks are full of recipes that offer egg substitutes. How good they are is another question.

I only recently realized just how much I rely on eggs in my diet. This was easy to ignore when the price for a dozen was cheap enough that I could splurge on the certified-humane, free-range kind without feeling like I’d spent my entire paycheck. Also, eggs are just easy: How many times a week have I made a last-minute lunch by frying an omelette or putting a fried egg on top of leftover rice faster than I could prepare anything else in my kitchen? In terms of both cost and versatility, eggs feel like the ultimate convenience food.

But yes, when a dozen started costing double digits, I realized I may have built myself a problematic habit. The eggs had taken hold of me, and I resented their absence.

This felt silly. For most of human history, people did not eat the amount of eggs I do year round. Even during times when eggs were plentiful, humans sometimes had to restrict their usage. So what better place to look to than to times of war, specifically World War I and World War II, to see how people on the home front substituted and rationed their way around eggs.

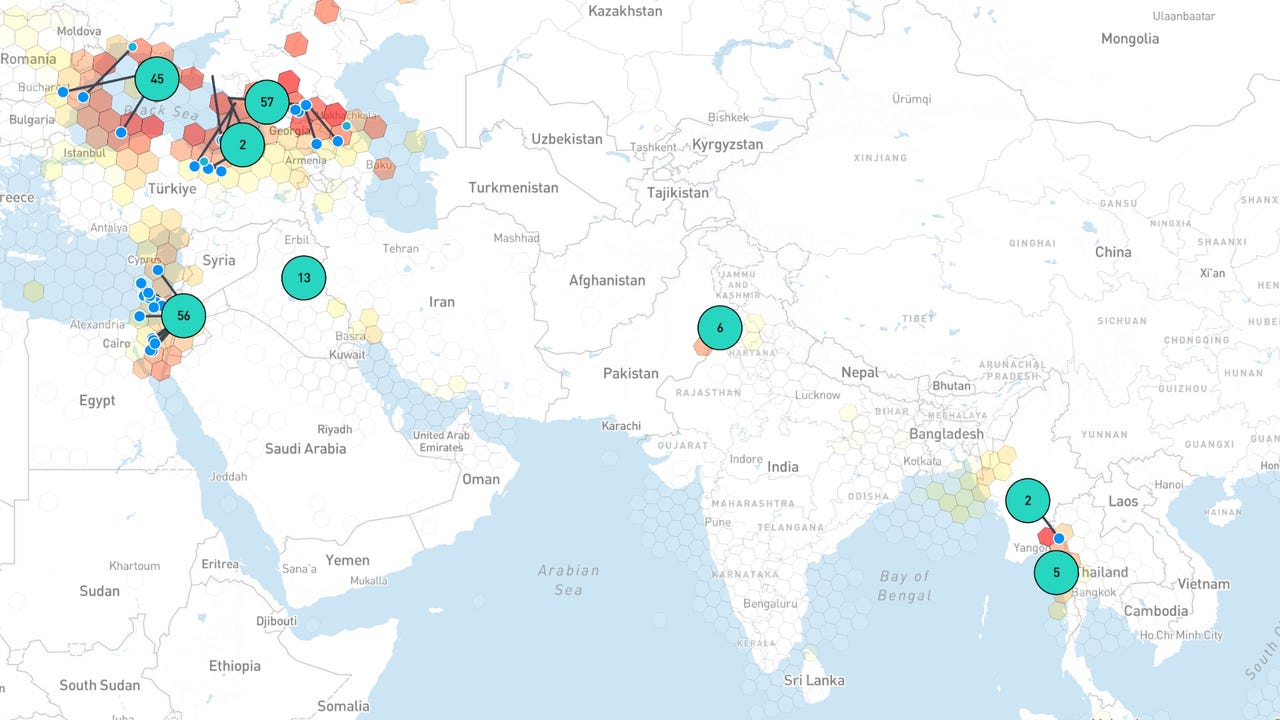

According to food historian Sarah Lohman, author of Endangered Eating: America’s Vanishing Foods, there are two main reasons a food would have been rationed during war. One, “foods that were shelf stable and portable were rationed so that they could be sent to feed military operations,” she says. So while items like fresh cheese were difficult to ship, hard cheese and dried fruit were rationed to feed the troops. The other reason for rationing came down to a disruption in lines of production, whether because the men farming the wheat for flour were now in the army, or because of conflict somewhere along the production and importing routes.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25938466/Rations.jpg) Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Eggs were heavily rationed in the UK during WWII. A quarter of the country’s eggs were shipped over from America during that time, and often arrived spoiled. Adults were limited to one egg a week, though exceptions were made for children, pregnant people, and vegetarians.

In the U.S., eggs were never rationed that heavily, though there were various wartime campaigns to ensure people weren’t wasting food. This poster from WWI encouraged Americans to keep hens and make money by selling the eggs during laying season, instead of selling the birds for meat. During WWII, The Victory Cookbook: Wartime Edition noted that eggs would likely face only “seasonable fluctuations,” and recommended them as a great source of protein and vitamins when meats were unavailable.

In the UK, packets of powdered eggs were also made available, although the taste absolutely left something to be desired. According to Lohman, the trick was to use them to supplement other baked goods. “You can put some dried eggs in gingerbread and be fine,” she says, and get a bit of added protein.

Wartime cookbooks also had tips for avoiding egg usage during economic depression. Lohman’s copy of The Victory Cookbook said that in butter cake recipes, “the number [of eggs] can be reduced to 2 ½ teaspoon baking powder for each egg omitted.” Many other wartime cake recipes, like this one from the BBC, use baking powder and vinegar to mimic the rise that eggs provide in baked goods. And the 1938 Davis Master Pattern Baking Formulas has a section on “one-egg cakes.” How good these recipes are is another question, however. Most war cakes were overly crumbly or dense, not exactly a mimic of an airy yellow birthday cake. And other substitutions were slightly questionable, like those of margarine and water in place of eggs.

I decided I should give one a shot. I’d made eggless fruit cakes before, so I chose something for which it feels like excluding egg might be a real stretch—a recipe for eggless mayonnaise from a pamphlet for “tempting, thrifty wartime meals,” published in 1942 by PET evaporated milk, that illustrated all the ways its product could be used to stretch meat and substitute for other ingredients. The eggless mayonnaise recipe asks you to stir together three tablespoons of evaporated milk with oil, lemon juice, and the barest of seasonings. At first it looked like mealy salad dressing, and after a blitz in the blender it was still liquid instead of a spreadable condiment. It tasted like crayons.

“I wonder if this panic is more symbolic, that it’s something that we’re used to being cheap and plentiful, and when it’s not, it almost takes away a little bit of our American identity,” Lohman says of the egg price crisis. Though forging an identity around the availability of eggs is still a relatively new conceit: Eggs are a seasonal food, and before our time of (relative) abundance, people either utilized preservation methods like pickling or waterglass storage, or just waited until it was laying season again and eggs became cheap.

And now, we enjoy certain advantages earlier generations didn’t. As Lohman notes, we’re in a golden age of vegan baking. We can also look to other countries that have a long history of eggless cooking and baking, such as India. There’s no shortage of resources for figuring out how to make brownies or frittatas without eggs, when to substitute flaxseed and when to acknowledge that a banana isn’t an egg, you know? That said, I am absolutely guilty of assuming eggs should be in my fridge at all times.

Some argue that eggs should have always been this expensive, that their cheap pricing is a factor of exploitative and inhumane foodways that ultimately create crises like the bird flu pandemic, and that in a better society eggs would be a luxury item. I’m not sure I agree. Or yes, their cheap price absolutely hides other horrors, just like so many aspects of the food industry. But I also think the point isn’t to throw up our hands and say eggs should only be for the rich or those who have enough outdoor space to keep chickens (which are also subject to bird flu right now), but to figure out what needs to change so we can reach a happy middle ground: Where consumers can afford eggs, egg producers are paid living wages, and production methods are such that the birds aren’t crammed together spreading illness.

This will probably mean we all eat fewer eggs. Or maybe we’ll go back to a time when they were more seasonal and we have to remember how to store them for longer periods of time. But they also don’t need to be a save-up-all-your-ration-cards treat either. A better world is possible. And it does not have to include evaporated milk mayonnaise.