The Way of Tea: How a Canadian Martial Artist Became a Tea Master in Kyoto

First things first: tea is more than just a beverage.

Born in Canada, Randy Channell Soie’s journey to Kyoto began with a fascination for Bruce Lee and a move to Hong Kong in the 1970s to study kung fu. What began as a pursuit of martial skill evolved into a lifelong search for philosophical balance. That search eventually brought him to Japan, where he immersed himself in budo (Japanese martial arts) and ultimately found his unexpected path through a neighbor who happened to be a teacher of chado, or way of tea.

“The moment I entered her tearoom, I was struck by how the movements mirrored martial arts,” he recalls on the latest episode of Matador Network’s No Fixed Address podcast. “The way you bow, walk, hold an object—there’s shared discipline and control.”

Today, Soie is an author, tea master, and professor in the way of tea in Kyoto. In this interview held in Soie’s Kyoto tearoom, he explains how a single bowl of matcha can shift your perception of time, presence, and reality itself.

Soie refers to chado as a “composite art.” Through it, one encounters architecture, ceramics, ironwork, textiles, and calligraphy. His teachings and book, The Book of Chanoyu: Tea… the Master Key to Japanese Culture, explores these intersections. “You can’t understand Japanese aesthetics without understanding tea,” he tells No Fixed Address host Michael Motamedi.

Kyoto, where Soie has lived for over 30 years, is the spiritual home of tea in Japan. The first tea plantations, brought from China in the 12th century by the monk Eisai, were established here. The city remains a center for traditional arts, and practitioners of the Urasenke (which loosely translates to tea ceremony) tradition still train new generations of followers. Soie himself teaches at Doshisha University and remotely to students worldwide.

In chado, as practiced by the Urasenke school, tea is not merely a beverage. It’s an experience built on four ideals: wa, kei, sei, and jaku (harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility). Guests are not served; they are honored. The space is not decorated; it is curated with seasonal intention. “When I serve tea,” Soie explains, “80 percent of the experience is for the guest, 20 percent for me. But in truth, it’s reciprocal.”

The ceremony centers on presence. The Japanese concept of ichigo ichie — one time, one meeting — guides every gathering. “You could repeat every movement tomorrow and it still wouldn’t be the same,” he says. “That moment only exists once.”

The deeper one listens to Soie, the more chado emerges as a metaphor for life. The process demands resilience. “Even in tea, things go wrong,” he says. “But you keep going. You don’t let it show. That’s hataraki — the ability to adapt.” The practice also instills humility. “After 30 years, I know I haven’t even scratched the surface.”

In a world consumed by digital distraction, Soie’s work is a quiet counterpoint.

“The past is the past, the future is unknown,” he says. “But this moment, right here, is real. That’s where beauty lives.” ![]()

![[DEALS] The 2025 Ultimate GenAI Masterclass Bundle (87% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

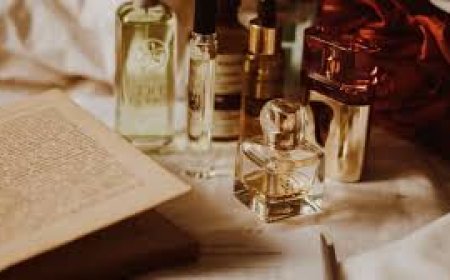

-Olekcii_Mach_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Air Traffic Controller Claps Back At United CEO Scott Kirby: ‘You’re The Problem At Newark’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/scott-kirby-on-stage.jpg?#)