The secret division keeping Americans apart

Americans are deeply disconnected across socioeconomic lines, and addressing these class divisions offers an overlooked way to bring Americans together, regardless of their politics.

When asked earlier this year to choose a word to describe their country, Americans across the political spectrum most frequently chose “divided.” This should come as no surprise — Americans feel divided, especially when it comes to politics. But underneath these often-emphasized political divisions lies another division: Americans are deeply disconnected across socioeconomic lines.

The rich and poor live increasingly separate lives, a fact that has profound consequences for the nation’s economic and political systems. While Americans and their leaders are often fixated on political polarization, addressing class disconnection offers an overlooked way to bring Americans together, regardless of their politics.

As recently as a few decades ago, Americans regularly came into close contact with people from across the income spectrum. White- and blue-collar workers lived in the same neighborhoods, sent their children to the same schools, and joined the same sports leagues.

Not anymore. Due to a variety of factors, ranging from restrictive zoning rules to reduced municipal swimming pool budgets, the rich and poor live different lives. From January 2019 through late 2021, Americans in four cities were up to 30 percent less likely to visit neighborhoods where residents had different incomes from them, even accounting for reduced travel during the height of the pandemic. American neighborhoods are far more racially diverse than they once were but remain stubbornly economically homogeneous. As a result, economically distressed communities are particularly isolated, with few social connections to those at higher levels of wealth.

Socioeconomic mixing is vital for the American Dream. Research finds that cross-class relationships are a crucial determinant of upward mobility. Exposing someone from a lower income background to those of higher income provides a role model for educational and employment goals and opens doors to internships and jobs they might not have otherwise.

Cross-class connections would be important even if they did not advance upward mobility. Constitutional democracy flourishes when people feel common purpose with one another, and it is impossible for people who never come into contact to build that common purpose. Initial research has even found that people who live in economically diverse communities have more positive perceptions of people who disagree with them politically.

Simply bringing people from different backgrounds together is not enough. After all, cross-class interactions happen all the time between workers and customers in places like gas stations and grocery stores. These interactions, though, do not place people on an even footing and are unlikely to build lasting connections.

One study finds the most economically diverse spaces in American life are restaurants like Olive Garden, IHOP and Chilis. But unless restaurant goers become comfortable with a lot more family-style meals, these chains are unlikely to create opportunities for ongoing connections between different groups of people.

Thankfully, the fate of economic connectedness does not depend on the nation’s appetite for baby back ribs. A project from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences highlights organizations that are building space for cross-class connection, from a rowing club in Boston to an apprenticeship program in Indiana to libraries in Ohio and Hawai’i. Much attention has been given in recent years to programs that bring together Americans of different political beliefs. Efforts to connect people across class lines deserve similar investment so they can proliferate across the country.

Making cross-class connections is not easy, but Americans recognize the importance of doing so. New research from More in Common finds that majorities of both lower- and high-income people have at least some interest in greater integration with those of different economic backgrounds. However, due to a mix of public policy decisions and individual decisions, these opportunities are sorely lacking in American life.

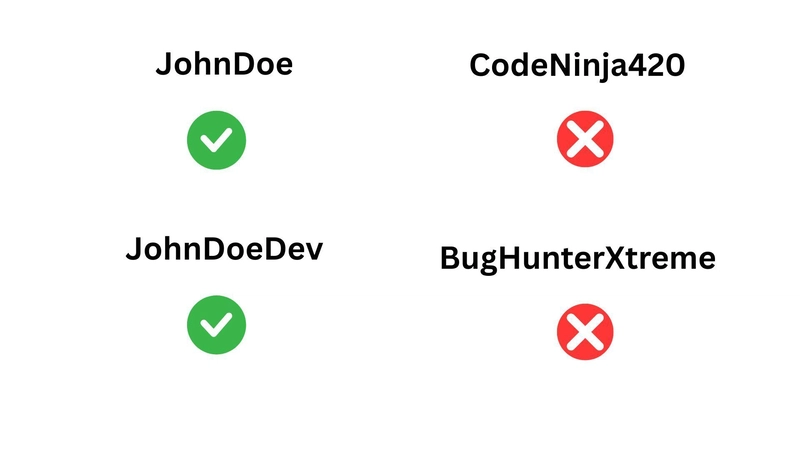

Someone, then, needs to make the first move, to disrupt their routine and make a conscious, concerted effort to get to know people on the other side of the economic ladder. Understandably, some lower-income people, though eager for more connection in general, remain apprehensive about connecting with those wealthier than them. “I think it would be an uncomfortable experience to interact with someone who can’t understand my experiences,” one 23-year-old Californian told More in Common.

Wealthy Americans need to prove him wrong. By reentering the public spaces from which they have retreated, they can help the nation return to a time of socioeconomic connection. In addition, by engaging in local institutions where people from different backgrounds can connect — like libraries, community centers, and public parks — Americans of all circumstances can put themselves in position to meet with new kinds of people on an even footing.

Rebuilding connections across economic lines won’t happen overnight, but such connections can help Americans overcome many of the other differences keeping them apart. Individual action, as well as intentional investment in community spaces, can help Americans step outside their familiar circles and embrace the connections that will build a stronger and more unified national community.

Katherine J. Cramer is a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Jason Mangone is the U.S. executive director at More in Common, a research organization that seeks to understand the forces driving us apart.