Scrapping these green energy subsidies could save the Inflation Reduction Act

They should use a two-pronged approach: scrapping the credits that don’t work and simplifying the ones that do by getting rid of the “everything bagel” provisions weighing them down.

Congressional Republicans are looking for ways to pay for extending the tax cuts scheduled to expire at the end of the year. Repealing the green energy tax subsidies expanded or introduced in the Inflation Reduction Act is an appealing option. We at the Tax Foundation estimated repealing all of these tax breaks would raise $851 billion over the next decade.

However, several House Republicans recently signed a letter defending parts of the act. Partial repeal could still raise significant revenue. If lawmakers choose this path, they should use a two-pronged approach: scrapping the credits that don’t work and simplifying the ones that do by getting rid of the “everything bagel” provisions weighing them down.

The Inflation Reduction Act introduced or expanded more than 20 tax programs with the primary goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, most modeling of the act shows the law is most effective in reducing power sector emissions.

Subsidies for transportation and buildings do not deliver the same climate benefits. In the case of the electric vehicle tax credits, studies from both before and after the Inflation Reduction Act have found that most credit recipients would have bought electric vehicles anyway.

Nonetheless, the credits’ costs keep rising. Thanks to new Environmental Protection Agency tailpipe regulations and holes in the electric vehicle credits’ structure, the Congressional Budget Office added $224 billion to the credit’s estimated revenue cost in 2024.

The electric vehicle credits and residential subsidies also flow to higher-income people. Initial IRS data indicates 67 percent of residential energy credit dollars went to taxpayers earning more than $100,000. Historically, electric vehicle credits have also been skewed to wealthier households.

The Inflation Reduction Act added some eligibility limits for high-income taxpayers, but the rules have workarounds, and even with the rules, electric vehicle credits can still disproportionately flow to affluent upper-middle-class folks.

We at the Tax Foundation estimated that repeal of the electric vehicle tax credits, the clean fuel production credit and four tax provisions related to residential and commercial buildings would raise $296 billion in revenue over the next 10 years.

While $296 billion is significant, congressional Republicans need much more to extend the expiring tax cuts, which cumulatively will cost $4.5 trillion over the next decade.

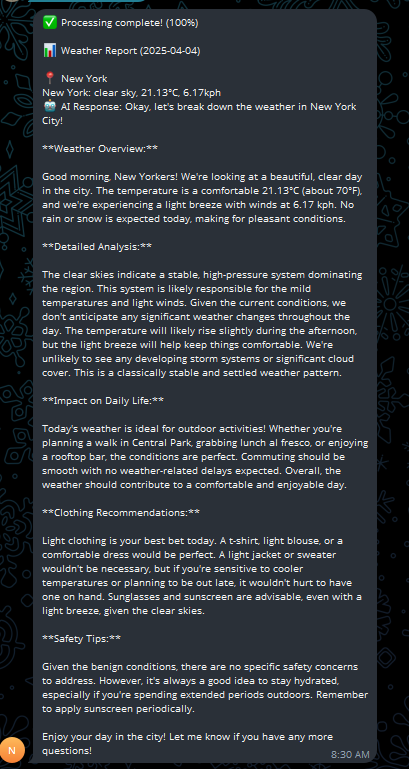

Enter the power sector tax credits. While they are more effective than the electric vehicle subsidies, they are needlessly complex. Driven by a Biden administration preference for “everything bagel liberalism” — a term coined by New York Times columnist Ezra Klein to describe a policymaking approach built on trying to do everything, everywhere, all at once — the power credits are saddled with new requirements and redistribution schemes.

Many credits are reduced by 80 percent unless taxpayers comply with prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements. These requirements are potentially more costly to comply with than the already-expensive Davis-Bacon requirements placed on federal contracts.

The clean electricity production credit and clean electricity investment credit include bonus credits for projects located in predesignated regions and/or that use domestic content.

Policymakers could replace the new tech-neutral clean electricity production credit and clean electricity investment credit (the latter featuring a prevailing wage and apprenticeship-compliant credit of roughly 3 cents per kilowatt-hour in current dollars) with a simple clean electricity production credit of 1.5 cents per kilowatt-hour, and no additional bonus credit options.

Instead of choosing between the clean electricity investment credit and the clean electricity production credit, projects would all use the clean electricity investment credit because its design is more effectively targeted.

We estimate this option would raise an additional $207 billion in revenue over the next decade. And that focuses solely on the clean electricity credits.

Policymakers could raise additional revenue by simplifying the structure and reducing the maximum subsidy for other Inflation Reduction Act provisions, such as the clean hydrogen tax credit, the zero-emission nuclear power production credit and the carbon oxide sequestration credit.

Ideally, policymakers would scrap the Inflation Reduction Act entirely and replace it with a low carbon tax — a $12 per ton carbon tax would produce the same emissions reductions as the act while raising revenue, instead of costing it.

Short of that, policymakers should begin with the low-hanging fruit: junking credits that do not effectively serve their purpose. After that, they should move on to simplifying the remaining credits.

Lowering the tax credit rates while removing the everything bagel add-ons could preserve emissions reductions while reducing fiscal costs and tax code complexity.

Alex Muresianu is a senior policy analyst at Tax Foundation.