Rare earth, hard choices: America’s Haqqani gambit in Afghanistan

A realignment inside the Taliban, an unspoken preference for U.S. partnership and a recognition that isolation is a dead end — represents one of the few real openings since 2021.

Afghanistan hasn’t been in the headlines much lately. It’s slipped into the background of American consciousness — just another unfinished story in a long list of slow-burning global flashpoints.

But out of the attention span of the West, something is shifting that deserves attention.

Since the U.S. withdrawal in August 2021, the Taliban haven’t operated as a single, unified movement. Power has quietly shifted between two rival factions: the Kandaharis — hardline, ideological and socially rigid — and the Haqqani network, a more pragmatic group known for intelligence ties, political instincts, and long memory.

Since the withdrawal, the Kandaharis, led by Taliban Supreme Leader Hibatullah Akhundzada, called the shots. They imposed restrictions on girls’ education, shut down civil society and kept foreign engagement at arm’s length. It was rule by isolation and decrees.

The Haqqanis, for their part, stayed in the background — watching, waiting, building alliances and letting the other faction absorb public frustration. That wait-and-see approach may be over.

In recent months, Sirajuddin Haqqani, the network’s leader and Afghanistan's interior minister, has stepped into the spotlight. He has been giving interviews to international outlets, hinting at economic revitalization and even suggesting a return to school for girls.

It’s not a full reversal of Taliban rule, but it’s a tonal shift — a signal to the outside world that not all doors are closed.

Adding to this picture, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, leader of Hezb-e Islami, Afghanistan’s second-largest militant group, has voiced concern over the country’s direction under Taliban rule.

A former mujahideen commander and longtime Islamist figure, Hekmatyar warned Afghanistan is “not moving in the right direction” and has suggested a ‘dignified council’ assist the government. Notably, he has aligned more closely with the Haqqani faction, signaling broader discontent with Kandahari leadership and adding weight to the possibility of an internal shift.

If that’s what it is, then it’s time the U.S. started knocking.

The Haqqanis are not reformers in any Western sense. They are not allies. But they are power players who understand leverage, and they see that Afghanistan’s economy is still on life support.

Any U.S. overture would carry political risk and draw scrutiny. Engaging with them would require strict conditions, oversight and a clear-eyed understanding that this is leverage, not legitimacy.

With aid frozen, jobs evaporating, and the banking system teetering, over 90 percent of Afghans are living below the poverty line. Humanitarian shipments, informal trade and whatever cash remains in the depleted system fuel the country. The Haqqanis know this is not sustainable.

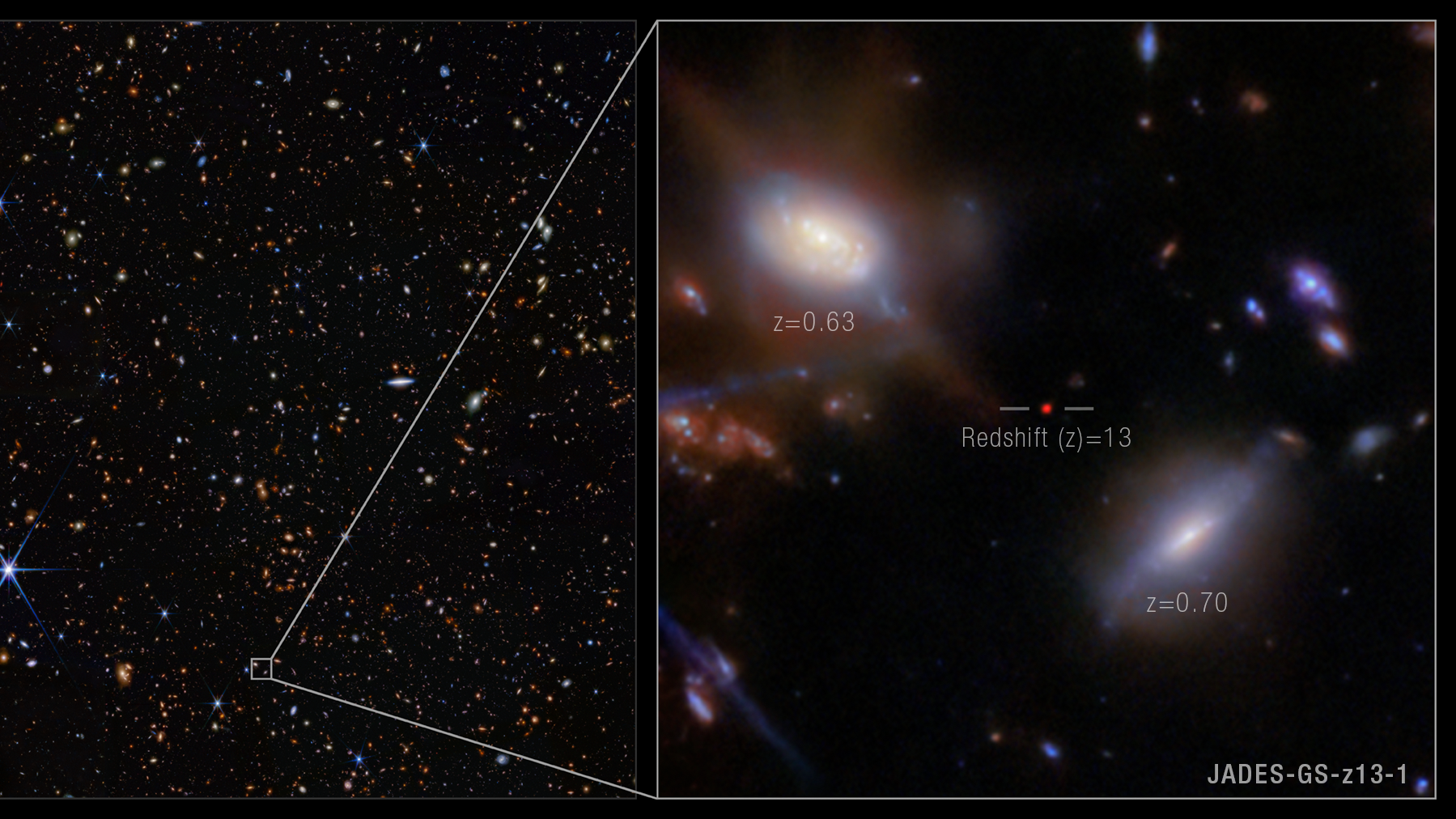

What most Americans may not realize is that Afghanistan sits atop vast untapped mineral wealth — an estimated $1 trillion in resources, including copper, iron, rare earth elements and, most significantly, lithium.

China already dominates the global lithium supply chain, and recently suspended rare earth exports to the U.S. in response to the Trump administration’s tariffs. In Afghanistan, since the U.S. withdrawal, Beijing has moved aggressively to close mining deals and infrastructure contracts that could cement its influence for decades. Iran and Russia are maneuvering, too.

But many Afghan leaders, even within the Taliban, prefer working with the United States — not because they trust us, but because they respect U.S. systems, contracts, transparency and accountability. They may not say it publicly, but quietly signal they don’t like China’s fast deals and their long-term costs.

This isn’t a call for recognition or a major infusion of humanitarian aid. It’s not about revisiting the past. It’s about understanding that in the power vacuum left behind, the U.S. still holds cards — it just needs to play them wisely.

What would that look like?

First, start small and stay quiet. Identify sectors — mineral development, infrastructure, logistics — where limited engagement could unlock value and provide alternatives to Chinese dominance.

Bagram, the sprawling airbase, with its existing infrastructure and strategic location, could serve as a cornerstone for economic development and potentially house a discreet U.S. consulate to support commercial engagement. Tie cooperation to specific outcomes: reopening girls’ schools, allowing monitored trade and keeping humanitarian operations safe.

Second, offer intelligence coordination on the Islamic State branch that continues to menace Afghanistan. It’s a threat both the U.S. and the Haqqanis take seriously, and the Haqqanis have networks on the ground that could prove useful if a trust-building channel is opened.

But here’s the key: This initiative must not be driven by the same people who shaped the last 20 years. Former officials, Kabul-era consultants or Afghans who fled during the collapse cannot lead this effort. They bring too much baggage, mistrust and complication.

The U.S. needs fresh intermediaries, people who understand the new political terrain, who can talk without echoing the past and who can deliver conversations that focus on the future. That’s what credibility looks like now.

If the U.S. steps back and leaves the field open, China will move in. Beijing won’t ask about girls’ schools, and they won’t worry about development or labor rights. They’ll take the minerals, build the roads and tighten their grip. Russia and Iran will carve out their pieces too, building spheres of influence that make the region less stable.

Meanwhile, the Kandahari wing will grow stronger, bolstered by money and leverage the Haqqanis could have used to drive modest change. If the U.S. wants any say in what Afghanistan looks like five years from now, the time to act is now.

Afghanistan may never be the same. But it’s not done evolving. What’s happening now — a realignment inside the Taliban, an unspoken preference for U.S. partnership and a recognition that isolation is a dead end — represents one of the few real openings since 2021.

The U.S. doesn’t need to flood the zone. It just needs to re-enter the room.

We missed our chance to shape how the war ended. Let’s not miss the chance to shape what comes next. Open a quiet line. Put a real offer on the table — targeted, conditional and strategic.

And above all, send a new generation of envoys who are not tied to the ghosts of Kabul's past. There are no guarantees. But there’s also no excuse for missing the moment.

Ron MacCammon is a retired U.S. Army Special Forces colonel and former political officer for the Department of State. He has worked on humanitarian demining and conventional weapons destruction programs in Afghanistan and Africa.

![[Research] Starting Web App in 2025: Vibe-coding, AI Agents….](https://media2.dev.to/dynamic/image/width%3D1000,height%3D500,fit%3Dcover,gravity%3Dauto,format%3Dauto/https:%2F%2Fdev-to-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fuploads%2Farticles%2Fby8z0auultdpyfrx5tx8.png)

-RTAガチ勢がSwitch2体験会でゼルダのラスボスを撃破して世界初のEDを流してしまう...【ゼルダの伝説ブレスオブザワイルドSwitch2-Edition】-00-06-05.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)