Movies for the Freaks: Mark Anthony Green on “Opus”

An interview with the director of A24's new thriller about his time at GQ and balancing genre thrills with heady themes.

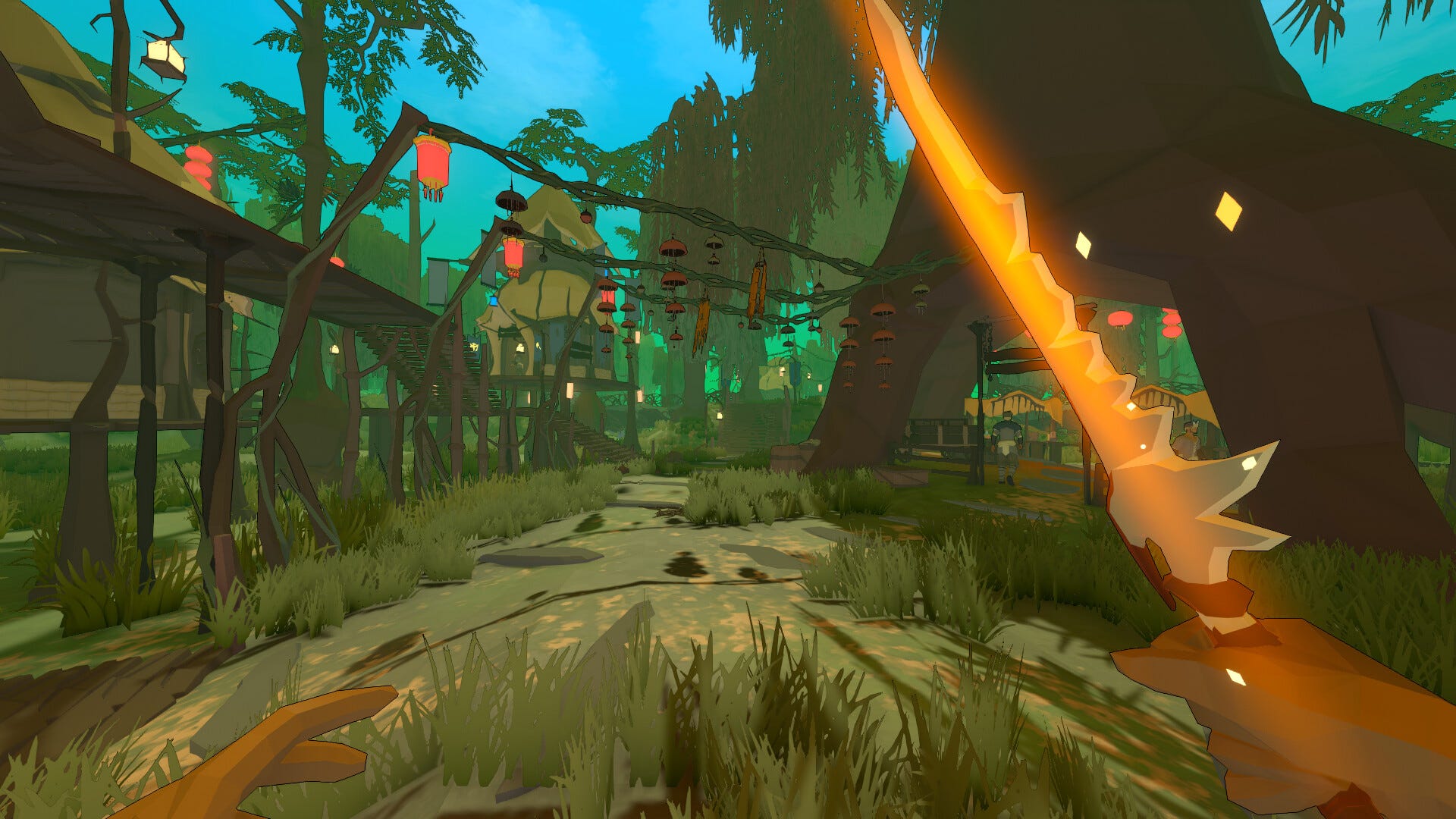

Director Mark Anthony Green’s “Opus” is a cautionary tale for an increasingly online world that conflates obsession with genuine connection. The film focuses on a legendary pop star, Alfred Moretti (John Malkovich), who announces to the world that he will release a new album after years of silence. For fans everywhere, this arrival is akin to the second coming of Christ (with much better music than any Biblical trumpet or horns can muster).

In anticipation, Moretti invites a few select members of the press to hear his album early at his isolated compound. Ariel Ecton (Ayo Edebiri) is one such lucky member and she goes to Moretti’s compound with her editor, Stan (Murray Bartlett). and meets a host of other guests with connections to Moretti, played by the likes of Juliette Lewis and Stephanie Suganami. As everyone around her becomes increasingly entranced by Moretti’s spectacle (and are more than happy to justify any realities that make them uncomfortable or seem strange), Ariel is the only one who begins to question that not all is what it seems at Moretti’s compound. The pop star may be promising something much more sinister than a simple career comeback.

For Green (for whom “Opus” is his directorial feature debut after a string of acclaimed shorts), he hopes his film sparks healthy conversations regarding the pitfalls of celebrity worship writ large. But he also hopes people walk away having a good time. The beauty is that he doesn’t see the two as mutually disconnected. “I make movies for the freaks and the movie nerds and the people that want to go for a cinematic experience and be challenged,” he shared.

The day after a packed early screening of the film at the Music Box Theater, Green spoke with RogerEbert.com in downtown Chicago about the line in the screenplay that motivated him to make the film, if he felt any trepidation about working with actors he may have written about during his tenure at GQ, and balancing the film’s heady themes with genre thrills.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity. This interview contains mild spoilers for “Opus.”

I read that your approach to filmmaking is that in your mind, you have one basket of things that you want to say about the world and another basket where there are worlds that are visually and culturally interesting to explore and that a film arises when you move something from one basket to the other. With “Opus,” which came first, the idea or the world?

I would say the thing I wanted to say about the world. That’s usually what comes first; it’s what you fixate on and what starts the writing process. You don’t direct the movie until you’re directing it, but the writing is where you can go on the journey and explore the idea.

You come from a journalist background and I’m curious if it was ever a struggle to think “Okay with some of these actors, I’ve profiled or written about them before … but now I’m directing them.” It’s a very different relationship when interacting with talent as a journalist versus as a co-creator and artistic collaborator …

For better and for worse, I didn’t do a ton of zooming out. I was so excited to make this film and loved every second of the process, and it’s much easier not to zoom out when you are enjoying what you’re doing. If I’m being honest, I haven’t zoomed out. I only started zooming out once I started doing these interviews, and I’m hearing people speak the connections and parallels back to me like, “Oh, you worked at GQ, and that must influence your filmmaking in some way.”

When you’re making it, you’re in the moment. When working with John [Malkovich], I wasn’t thinking, “Oh, I might have written about him.” I love “Veep.” It’s one of my favorite things ever made, so I loved that I could work with Tony Hale, but when you have 12 hours to get the scene, that’s the only thing you can feel in the moment. For better and for worse … I think for better. I want to honor and respect my actors; so much of that is being prepared and in that moment.

It’s easy for me to be in the moment when making it. It’s very hard for me to be in the moment when promoting it. I don’t know what that means … but it’s true (laughs).

There’s a humility that you need as a director when working with your actors but that’s a two-way street as well. I think about what you said in the Q&A after the screening about working with Nile Rodgers and The-Dream and how it takes a certain amount of humility for them to receive any feedback or constructive criticism from you about some of the song concepts they made.

The collaboration on this film is one of the things I’m most proud of. I’m grateful for the talented people who had to buy into my vision and who wanted to go on this journey with me and help me say the things that the film says. I’m so deeply proud and honored by that.

I make movies for the freaks and the movie nerds and the people that want to go for a cinematic experience and be challenged. I talked with John, Ayo, Murray, Juliette, and Stephanie so much about moments like last night’s screening at the Music Box … y’all are who we made this movie for. You are the type of audience we want to challenge and be in dialogue with. To see that start to happen is cool to me.

What’s striking about the film is that there are lots of themes you’re exploring about the pitfalls of celebrity culture and the dangers of parasocial relationships but it never feels preachy, only entertaining. I think of what you said about how you need to have the medicine with the honey …

A lot of honey … like an insane amount.

(Laugh) the throat will be very well taken care of. How are you thinking about getting the ratio of medicine to honey right?

The thing about medicine is that the medicine always has a controlled dose. The pill is one size … too much of it and it will kill you and not enough and the medicine is ineffective. Once the medicine is measured, that’s when I start to think “How much honey can we afford?” You’re getting the pill, so we might as well have the very best time we can have while taking this medicine.

On the earlier note about collaboration, in the film’s opening we see these individual shots of people at a concert reacting to Moretti’s music … it speaks to this sense that we can all experience the same thing but have vastly different responses. I’d love to hear about constructing that and the role of it in the film because we never quite get anything else like it for the rest of the runtime.

The pacing of this film is one of the things I’m the most proud of. I think that it is a challenge for some people to go to a movie that self-identifies as horror, and there isn’t a murder or something grotesque in the first ten minutes. That feels like a challenge and I like challenging films. Not only does that opening sink you in your seat, but because that song we hear at the beginning is so haunting and it’s juxtaposed with the cheering it sort of lets people settle in a little bit at a different register. Our sound designers, Casey and Trevor, did a great making the sonic elements of that scene sing. Then right after that opening, we’re in the conference room where we meet Ariel.

The most important thing to me in that first act was to establish that this is Ariel’s movie. I need the audience to not only see her at work but go on this date with her. I need you all to understand that she is not just fodder for the grotesque things that will commence. You have to care about what she wants and what she doesn’t have. You got to see her be a bit green. You got to get some of the heart in her … one of my favorite moments of the movie is when she just walks through the office. If you only saw that walk, you could derive a lot about that person from her walk.

The movie is an hour and forty-three minutes … I have to be thoughtful with my time. I love that what gets our attention and time in the first 15 minutes of this.

It’s a different gear … the calm before the storm.

Then obviously we go on a wild ride, but it feels cool and fresh to begin it at a different tempo.

The ending also strikes us differently. When we see her at the film’s conclusion, she too has fallen prey in some ways to the systems of fame and there’s a crowd of people looking at her, hanging on to her word, just like Moretti at the beginning.

I’m a terrible math student but I think of this movie like a parabola. “Opus” eases you in and then it ramps up … then all this shit goes down like we throw Murray Bartlett through a window and rip off Juliette Lewis’ scalp … and then at the end, we get to this psychological conversation. It’s dense but once again, it felt surprising to me and I wanted to earn that eight-minute scene at the end where we have John and Ayo sitting at a table talking … just two of my goats going to war.

It could have ended with “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” style, with Ariel leaving … but you have this interesting epilogue.

It’s funny because the first time somebody called it an epilogue, I said, “It’s not an epilogue.” Now I’m like, “It’s whatever people want it to be.” As long as you’re open to having the conversation.

That conversation at the end of the film is the reason I made the movie. That interrogation is dense and heady, but it’s a way for us to have a dialogue about why we choose the leaders we choose. Has the way we’ve chosen our leaders failed us?

There’s that line Morretti says: “With talent comes forgiveness.”

That’s the whole reason I made this movie. That idea … that’s the medicine … that’s the pill. Everything else is honey. The songs, the clothes, the scares, the technical work … all of that is so that when you get into the theater you can have a good time, and maybe by the time the film is done and we get to that scene, the audience is open to hearing “How we’ve been running this world and living our lives doesn’t serve us anymore.”

When I started writing this movie six years ago, things were really bad for queer people, black people, and women. It was bad and I think things have gotten worse. I think this movie unfortunately has become more relevant, not less relevant. So that ending conversation between our characters has become important to me. But the only way you get there is if the honey gets you there and makes you feel it. Looking at John and Ayo, I’m so immensely proud of their performances, and my fingers are crossed that people can take it all in. All I want is for you to swallow the pill and for the medicine to go into the bloodstream.

The allure of celebrity is that once you reach a certain status, you can move through the world in a different way were the rules don’t apply to you anymore. You follow the rules to gain a certain status where you don’t have to follow them anymore.

It’s not just in the entertainment industry. I won’t say names because it’s lame to say names but there are glaring examples of people like that who come to mind that I could have never even dreamed of when I started writing this script.

Art is supposed to challenge us and make smart people and thoughtful people ask questions. Is the system we have in place what we need? How do things get better? I think “Opus” is a really fun way to get people to have that conversation.

I’m thinking of that scene where Ariel seems to be the only one concerned with Moretti’s cult-like rituals at the compound. Everyone else dismisses her concern and attributes any strangeness to talent and genius. We need the Ariels who make us pause and say “There’s something weird about all this.”

I look at Ariel as a hero. The ending is complicated, but just because she may have fallen prey to the system, I don’t think she’s any less of a hero. But it is not my intention nor my read of the film, nor my opinion of the world to be anti-media, anti-journalism.

“Opus” opens in theaters March 14, via A24.