Jazz Is Profoundly American

Elizabeth Alexander explains why jazz music must be preserved.

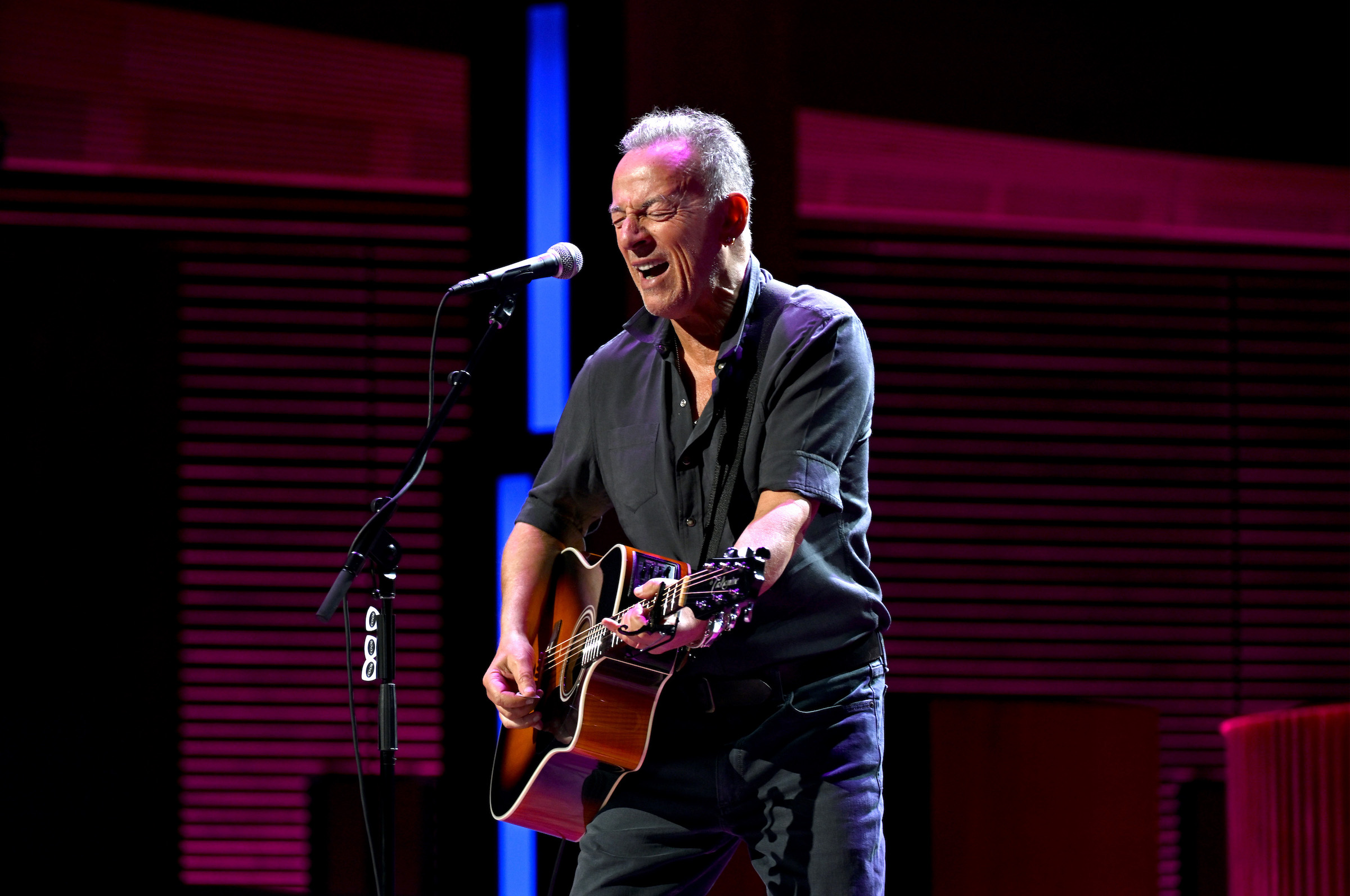

In November 2024, I went to see the jazz pianist Jason Moran perform at the Village Vanguard in New York City. Playing the music of Duke Ellington, this visionary artist of the hip-hop generation crafted a magical set, sampling a scrap of this and scrap of that, interpreting the songs of the jazz legend Ellington into something new and equally powerful. Across the various polyrhythms, Moran modeled how jazz can make more than one thing happen at the same time, and do so harmoniously. The effect was profound—and deeply American. [time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

As I was reminded throughout that evening, jazz is the most fundamental expression of innovation and creativity in American society, and as such must be both uplifted and protected. Shaping and infusing the arts and culture in their many different forms in our country, jazz lies at the heart of our great experiment. It was first pieced together in New Orleans by the cornetist King Buddy Bolden, who was born the year Reconstruction ended, and who drew on both the Blues traditions of Black evangelical churches and the ragtime of French-speaking Creole Black musicians.

Read More: How Jazz Became the Voice of Revolution

From its very beginnings, jazz has been a Black art form that is quintessentially American, and the first original art form to be invented in our young country. By the 1930s, nearly all of the number one musical artists in the United States were considered jazz artists; in the following decades, jazz musicians like Fats Waller, Benny Goodman, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat King Cole topped the charts. Drawing on the creative roots of jazz today are rap and hip-hop, among the most popular music genres in our country, and emblematic of the kind of artistic resourcefulness that the poet Amiri Baraka has characterized as “the digging of everything.” Out of the privation, the challenge, and the censure of slavery and the unfulfilled promise of post-Reconstruction justice, Black musicians embraced experimentation and innovation, ingenuity and joy, and a multigenerational call and response speaking truth to power that endures to the present day.

“Jazz is freedom,” Duke Ellington said in 1945. “Jazz is the freedom to play anything, whether it has been done before or not. It gives you freedom.” His words lay bare what makes the multivocality and polyphony of jazz so constitutive of Americanness. Our country is a place made of many places. Our primary language is one made of many languages. We are not by any measure “mono”—not monotheistic, not monoracial, not monolithic in our media or markets, our education or endeavors, our political beliefs or backgrounds. What we are is multivocal, multicultural; and we are free.

It’s no wonder then that jazz and the freedom it carries and conveys have long flourished in New York City, and those places like the Village Vanguard where I heard Moran remix and reimagine Ellington’s work. The long, slim, cheek-to-jowl island of Manhattan is a place where so much unique culture has been unbridled in its cultivation. The Vanguard, for example, is the oldest continuously run jazz club in the world. It is a small, persistent, and powerful space that holds so much sanctuary as well as beauty and exaltation, as evidenced not only during live performances but also through the iconic jazz recordings that have been completed there, including those of Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane in the 20th century, and Geri Allen and esperanza spalding in our current one.

During his Vanguard set, Moran at one point paused to hold up a talisman. It was Duke Ellington’s address book, and it was a physical manifestation, as he held it in his hands, of the intergenerational dynamism inherent to jazz. This is an American art form that has a known beginning. By playing gigs together, by sharing stories from teacher to student—from one artist down to the next in time, jazz has a starting point, and it is one that all jazz musicians know and experience. King Buddy Bolden discovered Edward ‘Kid’ Ory, who later played with Louis Armstrong. Miles Davis, who was in the lineage of Benny Goodman, mentored Jack DeJohnette, who mentored Terri Lynne Carrington. The distance from Bolden to the present day is only six generations, but the mentorship, stewardship, and transmission of this most American music has always depended on elders of the craft. And that is where an urgency now lies.

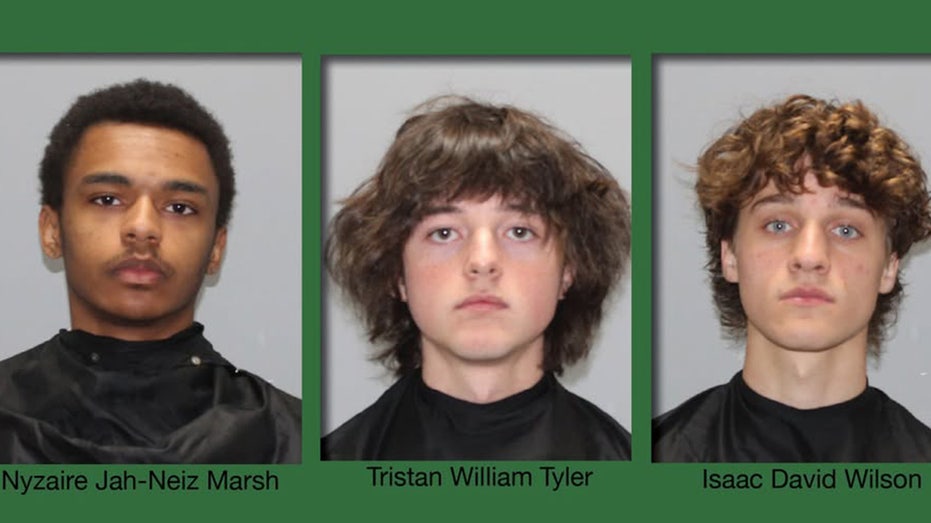

Not long after I saw Moran perform, the New York Times ran a feature on that most famous image of American jazz musicians in the mid-20th century. Entitled “Harlem 58,” it’s commonly referred to as “A Great Day in Harlem” and was photographed by Art Kane. The picture depicts 58 jazz artists in front of a brownstone on East 126th Street.

Only one of them, the jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins, is still alive. Rollins, who is now 94 years old, was quoted in the article as saying this of the elders he stood beside: “I had been following jazz all my short life up to that time, so I knew a great deal about the guys. My particular idols, Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young, were both in that picture. Those guys are much beyond me, but I guess I’ll be remembered with them when people look at this picture: ‘Oh, there’s Sonny Rollins, and wow, look, there’s Coleman Hawkins!’”

The learning and the guiding intrinsic to those various lineages—that relational excitement, energy, and awe that Rollins, now an elder himself, still so clearly recalls—must be preserved if we want jazz to persist as an artistic driver of innovation and creativity in our country.

One of the things a great jazz musician like Moran shows us is that if we do not listen to each other keenly, then we will not be able to function together in community—just as by listening to our shared history, we can better strengthen our American society. Jazz is often thought of as a “playing” art, but actually, it is a “listening” art. There is no jazz, there is no America. Without that call and response, they must always be, as Wynton Marsalis once said of our democracy, “in swing.”