Is Popular Culture Really in Terminal Decline?

An emerging critical consensus argues that we’ve entered a cultural dark age. I’m not so sure.

Illustrations by Javier Jaén

Last year, I visited the music historian Ted Gioia to talk about the death of civilization.

He welcomed me into his suburban-Texas home and showed me to a sunlit library. At the center of the room, arranged neatly on a countertop, stood 41 books. These, he said, were the books I needed to read.

The display included all seven volumes of Edward Gibbon’s 18th-century opus, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire ; both volumes of Oswald Spengler’s World War I–era tract, The Decline of the West ; and a 2,500-year-old account of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, who “was the first historian to look at his own culture, Greece, and say, I’m going to tell you the story of how stupid we were,” Gioia explained.

Gioia’s contributions to this lineage of doomsaying have made him into something of an internet celebrity. For most of his career, he was best-known for writing about jazz. But with his Substack newsletter, The Honest Broker, he’s attracted a large and avid readership by taking on contemporary culture—and arguing that it’s terrible. America’s “creative energy” has been sapped, he told me, and the results can be seen in the diminished quality of arts and entertainment, with knock-on effects to the country’s happiness and even its political stability.

He’s not alone in fearing that we’ve entered a cultural dark age. According to a recent YouGov poll, Americans rate the 2020s as the worst decade in a century for music, movies, fashion, TV, and sports. A 2023 story in The New York Times Magazine declared that we’re in the “least innovative, least transformative, least pioneering century for culture since the invention of the printing press.” An art critic for The Guardian recently proclaimed that “the avant garde is dead.”

What’s so jarring about these declarations of malaise is that we should, logically, be in a renaissance. The internet has caused a Cambrian explosion of creative expression by allowing artists to execute and distribute their visions with unprecedented ease. More than 500 scripted TV shows get made every year; streaming services reportedly add about 100,000 songs every day. We have podcasts that cater to every niche passion and video games of novelistic sophistication. Technology companies like to say that they’ve democratized the arts, enabling exciting collisions of ideas from unlikely talents. Yet no one seems very happy about the results.

To a certain extent, such negativity may simply reflect an innate human tendency to fret about decline. Some of the most liberating developments in history have first triggered fears of social stultification. The advent of the printing press caused 15th-century thinkers to complain of mass distraction. In 1964, The Atlantic published an essay predicting, not unpersuasively, that rock and roll would only foster conformity and consumerism in young Americans.

[From the August 1964 issue: What do they get from rock ’n’ roll?]

For as long as I have been a critic at this magazine, I’ve tried to cut against the declinist impulse. The year I started the job, 2011, was a turning point of sorts: Spotify launched in America that July; Netflix debuted its first original series soon after. The brainy rock bands that I’d grown up loving—Radiohead, Wilco—were starting to fade in importance, but pop, hip-hop, and electronic music were cross-pollinating in fascinating ways. Understanding change, and appreciating how human creativity flourishes anew in each era, always seemed to be the point of the job.

Yet the 2020s have tested my optimism. The chaos of TikTok, the disruption of the pandemic, and the threat of AI have destabilized any coherent story of progress driving the arts forward. In its place, a narrative of decay has taken hold, evangelized by critics such as Gioia. They’re citing very real problems: Hollywood’s regurgitation of intellectual property; partisan culture wars hijacking actual culture; unsustainable economic conditions for artists; the addicting, distracting effects of modern technology.

I wanted to meet with some of the most articulate pessimists to test the validity of their ideas, and to see whether a story other than decline might yet be told. Previous periods of change have yielded great artistic breakthroughs: Industrialization begat Romanticism; World War I awakened the modernists. Either something similar is happening now and we’re not yet able to see it, or we really have, at last, slid into the wasteland.

Stagnation

In 312 C.E., the Roman Senate ordered the construction of a gaudy monument called the Arch of Constantine. It incorporated pieces from older monuments, built in more glorious times for the empire, which had begun its centuries-long decline.

The Arch is one of Gioia’s favorite metaphors for modern culture. The TV and film industry is enamored of reboots, spin-offs, and formulaic genre fare. Broadway theaters subsist on stunt-cast revivals of old warhorses; book publishers rely disproportionately on backlist sales. Entertainment companies have long understood the power of giving people more of what they already like, but recommendation algorithms take that logic to a new extreme, keeping us swiping endlessly for slight variations on our favorite things. In every sector of society, Gioia told me, “we’re facing powerful forces that want to impose stagnation on us.”

The problem is particularly acute in music. In 2024, new releases accounted for a little more than a quarter of the albums consumed in the U.S.; every year, a greater and greater percentage of the albums streamed online is “catalog music,” meaning it is at least 18 months old. Hoping to remonetize the classics, record labels and private-equity firms have spent billions of dollars to acquire artists’ publishing rights. The reemergence of Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2022, 37 years after its release, seemed to signal that this was a good bet. A brief placement in a popular TV show (Netflix’s Stranger Things, itself a pastiche of 1980s movie tropes) could, it turned out, cause an old hit to outcompete most of the newer songs in the world.

“Music is turning into a rights-management business,” Gioia said. “There are vested interests now that don’t want new music to flourish. The private-equity funds just want you to listen to the same songs over and over again, because they own them.” The ultimate effect, he thinks, is to discourage true, daring artistry. If Bach were alive today, “he’d spend a few weeks trying to break into the L.A. music scene and say, ‘Ah, I’ll be a hedge-fund manager instead.’”

Gioia, 67, knows something about greatness thwarted. He started his career as a consultant, working for Boston Consulting Group and McKinsey. But he moonlighted as a jazz pianist, releasing two albums and gigging around the world. At one point in our conversation, he pulled up a recording of himself playing piano in 1986—before he suffered a debilitating case of arthritis in his 30s. “These arpeggios, I can’t do this anymore,” he said. “I always felt that if you give me another nine, 12, 18 months, I can be as good as anybody in the world.”

Gioia’s background as both an aesthete and a quant gives his criticism its distinctive edge. He’s able to deliver clear, hardheaded analysis of an art form frequently discussed in soft abstractions. I’ve often found myself swept away by the force of his convictions. Still, I nursed some doubts about his claim that the arts are frozen in amber.

In a viral 2022 Substack post titled “Is Old Music Killing New Music?” (later republished by The Atlantic), Gioia described omens of stagnation in everyday life, such as when he encountered a “youngster” singing along to the Police’s “Message in a Bottle.” The example stung a bit: The Police broke up before I was born, yet I’ve been humming their songs my whole life. Of course, when I was listening to my parents’ records in the ’90s, no one was measuring the replaying of old music. Today, by contrast, every Spotify play is monitored and monetized.

So might Gioia be overinterpreting data showing listening habits that have long existed? He didn’t think so. “In my generation,” he said, “nobody I know listened to their parents’ music.”

Gioia’s generation is the Baby Boomers, which, more than any since, conceived of itself as revolutionary. The rock-and-roll movement gave Boomers a fresh, elders-offending sound to call their own, and as they aged, they witnessed other breakthroughs: punk, hip-hop, electronic music. Gioia asked me to compare that dynamism with what’s happened—or, rather, not happened—in the 21st century. “The music today doesn’t sound that much different from 20 years ago,” Gioia said.

I turned that assertion over in my head. The radio does play new music that feels old, such as Sabrina Carpenter’s disco bop “Espresso” and Benson Boone’s classic-rock-flavored anthem “Beautiful Things.” But it also plays musicians who seem firmly planted in the present. Billie Eilish’s blend of jazz and electronic music diverges from the work of any pop star before her. Shaboozey combines country music and rap in a way that, perhaps for the first time in history, doesn’t feel like a joke. Reggaeton, Afrobeats, and K-pop now reach English-speaking audiences to an extent that was unthinkable when traditional gatekeepers—major labels, drive-time DJs, Rolling Stone—held more sway. These developments may not be quite as paradigm-shifting as rock and roll was, but they do suggest a culture that is still actively evolving.

Gioia acknowledged some bright spots for culture—he’s not entirely fatalistic about the status quo. He tends to view culture as moving in predictable cycles: When malaise and mediocrity reach an extreme, a revolution is likely to mount, upending the old order and installing a new one.

“Most people fundamentally want to have cultural experiences that are mind-expanding and broaden their world,” he said. “If the corporations that control our culture refuse to deliver that, they will find a way around it and there will be a rebirth. We will have a new counterculture.” He predicted a wave of “new romanticism” (emphasizing humanity over technology) and “new maximalism” (art made with unbridled ambition).

Gioia himself is trying to help bring a revolution about, albeit in small ways. Every day, he listens to hours of new music, searching for gems that the algorithms have ignored.

He showed me a draft of a post recommending nine new albums to his Substack readers. The lead image was of a young woman in a bonnet and stockings, sitting on a bed strewn with stuffed animals. This was Mei Semones, who sings dreamy bossa nova songs in English and Japanese. Gioia noted that three weeks after her album’s release, she had only 8,700 plays on YouTube. “I sometimes recommend albums that have less than 100 views,” he said.

To Gioia, the low listenership was evidence of the record industry’s efforts to smother new talents. But as I sat watching him pull up exciting find after exciting find, I started to feel oddly reassured about society’s creative energy. Today’s corporate behemoths may be powerful, and very often craven, but they’re reckoning with a force more destabilizing than Sgt. Pepper’s and London Calling ever were: a fractured global audience using technology to chase their obsessions, both familiar and novel.

Gioia went to YouTube and loaded another video, of the Australian band Glass Beams. Its members wore jeweled masks over their faces while playing intricate surf-rock grooves. “This band is great, and nobody’s heard it,” he said. “How many plays has it got?”

He scrolled down to the answer: nearly 1 million.

Gioia winced. “So it’s not as big a secret as I was making it out to be,” he said.

A few months later, I revisited the same video and saw that the play count had reached more than 6 million. The top comment read, “Praise to the algorithms for this!”

Cynicism

The title of the show was “Transcendence.” On the second floor of the prestigious Pace Gallery in Manhattan hung white-on-white abstract paintings and what appeared to be line drawings of rocks. Wall text explained that this was the first-ever U.S. solo exhibition for the 79-year-old artist Huong Dodinh. One painting was inspired by the first snowfall she ever witnessed, as a child, after the First Indochina War forced her family to move from Vietnam to France in 1953. The art critic Dean Kissick, wearing a baggy pink polo shirt and short athletic shorts, rushed through the room, barely glancing at the art. “I don’t think I can do this,” he whispered to me, stifling a giggle.

Kissick, 42, is a writer known in large part for his annoyance at the state of the art world. He believes we’ve been stuck in “the long 2017”: a period in which anxieties related to Donald Trump and Brexit have smothered culture with moralism, navel-gazing, and conformity. Although transcendence—achieved through beauty, originality, and skill—should be the primary goal, art has “become much more about messaging, raising awareness, or a kind of ambient healing of the world,” he told me. In other words, whereas Gioia awaits a revolution, Kissick thinks we’ve recently lived through one—and it’s made everything drearier.

We’d met up so Kissick could take me on a tour of the gallery scene in Chelsea. The Dodinh show, he explained, demonstrated a typical tactic among dealers these days: find a relatively obscure figure from an underrepresented group and try to sell his or her work, at least in part, on the basis of identity. The blander the art, the better for serving rich people looking to furnish tastefully understated homes. “This is just, like, sofas,” he said, gesturing toward Dodinh’s soothingly serene canvases. “Curtains.”

We stepped into an elevator, and I asked him whether he at least felt a sense of justice at seeing someone like Dodinh exhibited at one of the most exclusive galleries in the world. “I always like to see older Asian women doing well, because they remind me of my mother,” said Kissick, whose mother is a Japanese immigrant to the U.K. “But no—I don’t see justice.”

Last year, Kissick published a cover story in Harper’s arguing that politics had all but destroyed contemporary art. Museums and galleries were blending “all forms of oppression” into “one universal grief,” he wrote. “We are bombarded with identities until they become meaningless. When everyone’s tossed together into the big salad of marginalization, otherness is made banal and abstract.”

The essay opened with a shocking scene: In May 2024, on her way to see a show at London’s Barbican Art Gallery, Kissick’s mother was struck by a bus, an accident that resulted in the amputation of both of her legs. Kissick flew from New York to London to visit her in the hospital. Later, as she recuperated, he checked out the show she’d been on the way to see. Titled “Unravel,” it featured textile art, primarily by artists from historically marginalized communities. As Kissick noted, the curators further “proposed that textiles themselves had also been marginalized, having been gendered as feminine and regarded as ‘craft’ rather than ‘fine art.’ The show’s introductory text asked, ‘What does it mean to imagine a needle, a loom or a garment as a tool of resistance?’ ”

Kissick’s assessment was withering:

It was the most depressing exhibition I had ever seen at the gallery, hardly worth a visit, let alone losing one’s legs. While Unravel pretended to be politically radical—even revolutionary—it didn’t seem to stand for much beyond liberal orthodoxy and feel-good ambient diversity. It offered fantasies of resistance, but had little to offer in terms of genuine, substantive social change or artistic experimentation.

Critiquing progressive pieties in this fashion may simply sound conservative. Indeed, Kissick’s complaints are now reflected in the anti-DEI wave that has swept the federal government—and rippled through American corporate, cultural, and academic institutions. But Kissick insists he’s not ideologically motivated. “I just don’t care that much if people are very woke or very anti-woke,” he told me. “The conversation itself just takes up way too much space.”

That conversation has been as impossible to avoid in pop culture as it has been in high culture. Proponents of the theory that “representation matters”—meaning that more inclusive media will create a more inclusive society—have cheered diversely cast remakes of films such as The Little Mermaid, body-positivity choruses sung by artists like Lizzo, and reckonings with perceived cultural appropriation in the literary world. Conservatives, in turn, have organized a backlash, attempting to score ideological points by racking up streams and downloads. When Jason Aldean’s 2023 song “Try That in a Small Town” was criticized by some on the left for tacitly endorsing lynching, a right-wing campaign to support the track resulted in Aldean hitting No. 1 on the Hot 100. Similar campaigns boosted the box-office prominence of films such as the anti-DEI mockumentary Am I Racist? Even the most escapist forms of entertainment—blockbusters, pop concerts, children’s TV—are now treated like political battlegrounds, though you rarely hear about anyone’s opinions being changed in the skirmishes.

In the world of fine art, Kissick feels overwhelmed by what he sees as cynicism masquerading as idealism. He mentioned the example of Amoako Boafo, an in-demand Ghanaian painter who was hired to adorn the nose cone of one of Jeff Bezos’s rockets in 2021. At the time, a statement by Blue Origin, Bezos’s spaceflight company, announced, “His stunning portraits capture Black joy and the kind of shared future we hope to create for us all in space: vibrant, beautiful, and full of wonder.” One could be forgiven, however, for thinking the commission was motivated less by Black joy than by PR concerns around a controversial billionaire’s vanity project. (One could likewise be forgiven, judging by Bezos’s actions since Trump’s reelection, for wondering whether future nose cones will be similarly adorned.)

To some extent, I sympathize with Kissick’s complaints. Mediocre art really does get overrated on account of its politics. Any working critic knows how factional and reflexive audiences have become: Pan a woman, and many readers will call you sexist; champion one, and you risk being dismissed as a beta cuck. Such reactions don’t just represent the persistence of prejudice; they reflect an awareness of the way that “culture,” a supposedly binding force, has come to feel more and more like an embittered sports rivalry.

But any working critic will also tell you that topicality and identity have inspired incredible work in previous eras (just listen to Nina Simone) and recently (watch the post-#MeToo masterpiece Tár, about a lesbian orchestra conductor accused of misconduct). Even Kissick acknowledges this. He gushed to me about the artist Arthur Jafa’s 2021 video installation AGHDRA; its depiction of an ominous, undulating seascape evokes, as the artist told ARTnews, the feeling of “being chained in a slave ship.” Kissick even had kind words for Salman Toor, a much-hyped Pakistani artist based in New York who makes green-gray, impressionistic smudges of queer guys hanging out in bars or apartments. Toor typifies one of Kissick’s least favorite pairings—old-school technique with a 21st-century, identity-related twist—but at least, Kissick said, “he can really paint.”

As we hustled from gallery to gallery, popping in for mere minutes and then leaving, I began to get the sense that Kissick’s grudge against the art world goes deeper than politics. He deemed a colorful painting of motocross riders “rubbish.” A huge, haunting sculpture of a half-dressed woman with blurred features, as if rendered by rudimentary CGI, received just a murmured “Cool.” At one point, he acknowledged his jadedness.

“You can probably tell—I’ve seen too many white-cube shows of paintings in my life,” he said. “There’s too much art.”

This problem, if it can be called one, has escalated since around the time Kissick graduated from art school, in 2010. Back then, he felt, visual art was crossing over to become a mainstream cultural phenomenon—Jay-Z was rapping about collecting Basquiats, and Louis Vuitton was making handbags with the Japanese visual artist Takashi Murakami. The internet, it appeared, was encouraging audiences beyond the walls of galleries and museums to develop an interest in art. But hope for technologically enabled creative flourishing gave way to oversaturation and numbness. So-called zombie formalism—rehashed abstract expressionism optimized for Instagram shareability—became a fad. Minimalism, a presumed antidote to the chaos of online life, became the default aesthetic in art, fashion, and consumer-product design. “It’s been clear for a while that art’s running out of ideas,” Kissick declared in a 2021 column for The Spectator. The overvaluing of stale, activism-scented art is a symptom of all this burnout: If stylistic innovation can no longer break through the noise, we’re only left to argue over subject matter.

What would a better direction be? Kissick’s cagey on this question, but he has a few ideas. Art should capture its era, he said, but the culture wars are not the only important thing about the 2020s. Rather, he wants art to address the internet’s more ineffable consequences: rendering our thought processes glitchy, destabilizing our sense of self. He thinks artists should find new ways to use time-honored techniques, while also being open to experimenting with emerging tools, including AI. “The experience of being alive, this century, has changed dramatically,” he said. “We should engage with the times we live in, and then maybe we’d feel less hopeless about everything.”

What he really seems to be yearning for is a paradigm shift: some sort of formal leap forward combined with a spiritual reawakening. “The culture we have is so obsessed with ourselves, with people’s identities and personalities,” he said. “Perhaps we’ll be able to transcend that somehow. Perhaps we will get over this deeply individualistic, deeply self-obsessed moment.” He paused. “But I don’t know how that would happen.”

Isolation

KMUN-FM 91.9, a public radio station for the coastal town of Astoria, Oregon, broadcasts from a 133-year-old Victorian cottage with burgundy eaves and stained-glass windows. One rainy day last spring, I was greeted there by the 41-year-old musician and writer Jaime Brooks, who wore a tweed jacket over a T-shirt emblazoned with the slogan Foresight Prevents Blindness. She introduced me to a variety of friendly station volunteers working in studios cluttered with stacks of vinyl records, spindles of CDs, and well-worn instruments and mixing boards. On one wall hung a hand-drawn map of the station’s broadcasting area.

It was a strikingly analog setting in which to meet an artist who once embodied the internet’s futuristic potential. Best-known for her work under the aliases Elite Gymnastics and Default Genders, Brooks has long been a “bedroom musician”: someone who uses a home computer to make high-quality recordings. In the early 2010s, as a 20-something immersed in the hipster party scene in Minneapolis, Brooks collaborated with a friend to release a few ethereal dance songs that drew the acclaim of music bloggers. She was soon dating the similarly buzzy artist Grimes and living in Los Angeles, getting a close-up look at the modern pop ecosystem.

But these days, her mics and guitar are packed up in boxes, gathering dust. Spending time working on new songs just doesn’t feel right given her belief, articulated in widely circulated tweets and essays, that the music industry is doomed. Like Gioia, Brooks feels that tech and business interests are strangling the arts; like Kissick, she believes that most of the new work that gets made today just flat-out isn’t good. But Brooks’s view is even darker than either of theirs, and more explicitly personal. She described the future of music to me in one word: wreckage.

Many musicians believe that Spotify’s business model is predatory, forcing artists to participate in a system in which they make only a fraction of a penny whenever a song is played. Brooks agrees, but her concern runs deeper than the money itself; she argues that music’s role in society has been corrupted. Streaming encourages artists to play an enervating game of scale: The more songs they release, the more chance they have of going viral and turning pittances into real income. Artists are thus motivated to record as quickly and cheaply as possible. All of this, Brooks believes, has led to a glut of music—both popular and obscure—that is plainly bad: less distinct, less soulful, and less skillfully made than the minimal standards of previous eras. “Nobody can get the resources to develop their craft,” she said.

This decline in quality has created the conditions for what Brooks fears will come next: a flood of AI-generated songs that further devalue music as an art form and an economic enterprise. Already, streaming platforms have inculcated a huge demand for “utility” music, such as white noise to fall asleep to and “chill beats” to study to. Cheap AI tools can now conjure credible versions of such music, and over time they’ll only get better at imitating other styles. Listeners’ standards have become so diminished that they won’t be able to tell the difference.

Brooks saw the early stages of this catastrophe unfolding during her time in Los Angeles. While we chatted, she casually mentioned being on set at a Lady Gaga video shoot, and watching Ezra Koenig of Vampire Weekend play songs in his backyard. But to hear her describe it, her L.A. years were mostly disillusioning. “I didn’t really see a lot of success that I thought seemed desirable,” she said. “It’s, like, a lot of people sitting in rooms by themselves, ordering fucking Uber Eats.”

What she meant is that the ethos of the bedroom musician, once an indie phenomenon enabling outsiders to gain a foothold, quickly became the record-industry default. Producers can skip the studio to work on their devices at home, commissioning instrumentalists and beat makers who live time zones away. Music is now widely made much in the manner that it is consumed: by people who are alone, encased in their headphones.

This state of affairs, Brooks thinks, is antithetical to music’s purpose. Listening to songs once meant getting a window into specific, communal circumstances—into the churches where R&B evolved from gospel, into the block parties where hip-hop fermented, into the clubs where rock bands jammed. Now most music is shaped by and tailored to a fake place, an intangible scene: the internet. It only feeds the broader trends of cultural fracturing and personal solitude that are now clearly depressing people’s sense of well-being.

I share the feeling that the mundanity of streaming has made music feel smaller, less important, than it used to—but I see plenty of signs that the art form still serves a social function. One of the biggest stories in the record industry in the 2020s has been the boom of country music, a style that’s rooted in a sense of place and shared identity. New stars such as Zach Bryan and Lainey Wilson have been drawing droves not just to stream songs, but to sell out their tour dates and tailgate in the parking lot. New honky-tonks have been popping up across the nation, even in blue states.

“There’s still human culture that is being mined there,” Brooks said when we got to talking about country music. She pointed out that Taylor Swift’s success owes a lot to her having come up in Nashville, writing on guitar with seasoned songwriters, thus giving her skills that feel rarer with each passing year. But Brooks sees the country renaissance as a mere side effect of the genre being late to technological adoption, which isn’t the same as defying it. “Streaming is taking longer to eat it,” she said. “But streaming will destroy it.”

Eventual destruction is, in her view, the fate of most everything good about music and the broader artistic landscape. Gioia’s boom-and-bust trend forecasts, Kissick’s pining for creative reinvention—both sound naive in Brooks’s analysis. “When people use this language, ‘Oh, it all moves in cycles; it’s been going this way since time immemorial’—no, it hasn’t,” she said. “Like, in Joe Biden’s lifetime, the sheet-music industry was completely replaced by the record industry. And in our lifetime already, the practice of buying copies of records has been replaced by the concept of renting access to them.”

In other words: Great things don’t just change; they die, and what they’re replaced with may well be worse—if they’re replaced at all. As she wrote on Substack in 2023:

The history of the record business is not a story about rejuvenating cycles of natural death and destined rebirth. It’s a story about old, outmoded tech companies chasing diminishing returns. The path we’re on is a spiral, not a circle, and it’s getting smaller and narrower as we get closer to the end.

Hearing all of this made me particularly sad, because Brooks’s own music always seemed like an example of how to defy modern alienation. She left Los Angeles in 2018—around the time that Grimes started dating Elon Musk—and recorded three excellent albums about searching for connection in a world made cold by technology, greed, and, to quote one lyric, “crypto dipshits.” The music was electronic yet felt handcrafted, and Brooks, singing through a warbly vocal filter, sounded like a human trying to escape being turned into a machine.

For now, though, Brooks has put her music career on hold. The process of moving notes around on a computer screen, alone, started to feel “masturbatory.” A successful new album would “generate a bunch of value for Apple, for Spotify, for whatever other companies are taking pieces,” she said. “And I don’t feel good about that.” Now she’s been spending her days hanging out at KMUN, learning about the seemingly outmoded technology of terrestrial radio, which she thinks will gain a kind of “postapocalyptic” usefulness to humanity as the internet is overrun with AI slop.

Still, Brooks can’t stop dreaming of new music she wants to make. She described one song idea that’s been rattling around in her head lately: “It’s got horn solos, and it’s got, like, Andrews Sisters backing vocals in the chorus.” I suggested to her that she might benefit from a new record deal to bring that vision to life.

“Well, no,” Brooks replied. What she’s lacking is collaborators—real-life bandmates, bonded by shared experiences, with physical instruments and the skills to use them. “I need people. I need people who care.”

Acceleration

Each declinist I spoke with made a convincing case that large, inexorable forces were wearing culture down. But they also left me clinging to scattered counterexamples that might tell another story. I’d seen the omens of death; I needed to make an effort to find signs of life.

Which is how I ended up sweating in a poorly ventilated indoor skate park in Brooklyn one summer night. I was there for a concert thrown by No Bells, a hip-hop-focused blog that bills itself as “a hub of the wider internet underground.” Young people sat on either side of a half-pipe, looking like members of a very eclectic tribunal. They wore jorts and crop tops; or strappy, S&M-influenced getups; or pajamas emblazoned with cartoons. They fiddled with phones, lighters, Nintendo DSes, and, in one case, a unicycle. At the bottom of the half-pipe, a mosh pit swirled around a small stage. Two rappers shouted over a beat that paired incessant synthetic clapping with a sample of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” played on ukulele.

Within the scrum by the stage was Kieran Press-Reynolds, a 25-year-old journalist who seems like he should be a declinist, but isn’t. His father, the music critic Simon Reynolds, wrote the 2011 book Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past, which puzzled over the abundance of remixes, remakes, and revivals in the 2000s and made an early version of the stagnation argument now espoused by Gioia and others. Press-Reynolds himself has made a budding career out of chronicling internet subcultures that seem symptomatic of a society in crisis. When we met, he’d recently reported a story for The New York Times about a video game that satirizes online influencers by making players experience horrific things for content. For GQ, he’d delved into the “looksmaxxing” community: young men who, among other techniques for optimizing their physical attractiveness, try to alter their faces by clenching their jaw for hours a day, egged on by internet forums that are, he wrote, “cesspits of insecurities.”

And yet, Press-Reynolds is energized by the culture right now. “Maybe there aren’t amazing macro-trends at the moment,” he told me, but if you scratch the surface of the mainstream, “people are cooking.” As a critic, he feels an obligation to spread the good news. “Every young person deserves something to champion,” he said. “Something to get really feverishly excited about.”

Press-Reynolds keeps his brown hair long and scraggly; his voice is hoarse and giddy. He described his own artistic obsessions in terms such as “fried” and “anarchic.” In music, on TikTok, and even in web-design trends, he sees a turn toward an aesthetic he called “max stimuli,” which pushes the bounds of speed, dissonance, and silliness while recombining bits of old culture into something new. “It feels like how our brains feel now: infested and congested with so much stuff,” he said.

He’s particularly captivated by the hip-hop underground: a constellation of subgenres such as “rage rap” (which takes after the unintelligible lyrics and glitchy beats of the cult hero Playboi Carti) and “pluggnb” (a woozy, melodic version of trap). A global community of producers, swapping beats and software plug-ins online, is twisting hip-hop’s conventions to create sound sculptures that, Press-Reynolds thinks, “really could not have come out 10 years ago.” He mentioned a recent SoundCloud “micro-hit” called “fragged aht” by an artist named wokeups. The song “makes you think of a human expanding and deflating like an accordion,” Press-Reynolds said. I pulled up the track after we talked. A heavily filtered voice ululated about money and guns for two minutes over a swell of digital sound. The effect was weirdly beautiful; it gave me goose bumps.

Other genres are also getting scrambled in disorienting, playful ways. I’ve been fascinated by hyperpop, a loose term for the punkish, noisy spin that bedroom electronic musicians put on bubblegum tropes. In 2024, hyperpop had its commercial breakthrough with Charli XCX’s album Brat, whose frenzied rhythms became popular enough to be adopted by the official memes of Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign.

Brooks had warned me not to put much stock in internet-native music scenes; she dismissed most hyperpop as “regurgitated video-game soundtracks” made by and for people who have “never been to clubs.” This had struck me as uncharitable, though in talking with Press-Reynolds, I realized it wasn’t entirely untrue. He traced his own teenage musical awakening to playing Minecraft while listening to hip-hop set to anime montages on YouTube. His culture-critic parents (his mother is the writer Joy Press) would play the slick beats of Daft Punk around the house, but he gravitated toward the blown-out distortion of angsty rappers such as XXXTentacion. When the pandemic lockdown came, he burrowed even deeper into the digital wilds.

Being so online, Press-Reynolds joked, had inflicted him with “brain rot.” He makes no apologies for being a music critic who “almost can’t bear” to listen to full albums; sometimes he’ll just play a song for 30 seconds to “feel that texture.” This admission pained me a bit. I’ve felt my own attention span decaying in recent years, but I still cling to the idea that transcendent art—and transcendent experiences with art—requires sustained focus. In many ways, the problems that Gioia, Kissick, and Brooks spelled out were problems of terminally distracted audiences preferring junk (recycled IP, political bait, wallpaper music) to quality. What are we going to do about brain rot?

At the skate-park concert, it occurred to me that art itself might be the answer. The headliner was a trio—the rappers Polo Perks and AyooLii with the rapper-producer FearDorian, who hailed, respectively, from New York, Milwaukee, and Atlanta, but had linked up online and developed in-person friendships. Their songs deployed samples—emo rock, M.I.A., gaming music—with a kind of elegant dizziness, as if multiple browser tabs playing random audio were harmonizing together. A thwack on every eighth note, the signature beat of the recently ascendant Milwaukee rap scene, created a sense of Energizer Bunny propulsion. Sweating at the bottom of the half-pipe, pressed up against the crowd, I felt the music meet my own sense of distraction and supplant it. These artists had burst from the internet to convey feelings about friendship, partying, and hustling—the classic hip-hop rush, delivered with a sound that suits its times.

Afterward, I thought of the concerts in the 1981 documentary The Decline of Western Civilization, which followed the grungy, anti-establishment scene forming around hardcore-punk bands such as Black Flag. Its title evoked Oswald Spengler—and played as a joke about the way that elders often disdain cultural developments they don’t understand.

The 62-year-old Simon Reynolds sometimes feels like one of those baffled elders. He told me that much of the music his son champions is “too gnarly” for his ears. Still, seeing Press-Reynolds “chasing the latest convolution, the latest mutant” in music was a thrill: It’s what he used to do. His heyday of exploration was the ’90s, when the rise of electronica—techno, drum and bass, and, yes, Daft Punk—seemed as exciting to a young Reynolds as rock and roll had to the Boomers. Then he got older, the 2000s came around, and his generation of ravers started to lose steam. No comparable new scene seemed to be taking their place. So he wrote Retromania, about the feeling that culture had become too backward-looking. (Soon after, one of his good friends, the late Mark Fisher, wrote a similarly themed essay, “The Slow Cancellation of the Future,” that has become one of the 21st century’s most influential statements of cultural pessimism.)

But some of Reynolds’s bleakest theories, he told me, started to “crumble a bit” once they were published. Technologies such as streaming and social media began to upend the culture; Press-Reynolds kept discovering interesting oddities online. He realized that he’d been thinking of artistic evolution too narrowly. Innovation was happening; it just wasn’t the kind he’d been looking for. “I was very, very fixated in that book on sound,” he told me. He now believes music is about more than sound. It—and culture in general—is a “messy hybrid” of images, ideas, delivery methods, and so much else.

From that perspective, this decade’s culture is plenty dynamic. The great media of the 20th century—the art-pop album, the feature-length film, the gallery show, the literary novel—may be fighting for their life, but that’s because of competition from new forms defined by a sense of immediacy: short-form video, chatty podcasts, video games, memes. Like the old media, these forms foster tons of mediocrity. But they also invite surprising excellence: the minute-long songs of PinkPantheress, which glitter with detail and emotion; the writing of Honor Levy, who weaves lurid short stories out of internet slang. “It’s more of an aphoristic culture than an essayist culture, isn’t it?” Reynolds said. “You can say quite clever, profound things in just a few sentences.”

That sensibility emerged from the warrens of the internet, but it’s bleeding into the mainstream—and, in the best cases, energizing it. When Press-Reynolds described his idea of “max stimuli” to me, I thought back to a term Gioia had used: “new maximalism.” In Gioia’s analysis, the greats of his lifetime—Brian Wilson, Stephen Sondheim, Joni Mitchell—have been maximalists, translating grand ambitions into pop symphonies, stage spectacles, or emotionally dense story-songs. The cultural triumphs of this decade fit that model. Audiences still want storytelling they can chew on—they just want it in a form that’s attuned to the accelerated ways we now consume information. Artists are playing with tempo, intensity, and scale to tame the modern attention span, offer smart social commentary, and foster a feeling of connection in an era of isolation.

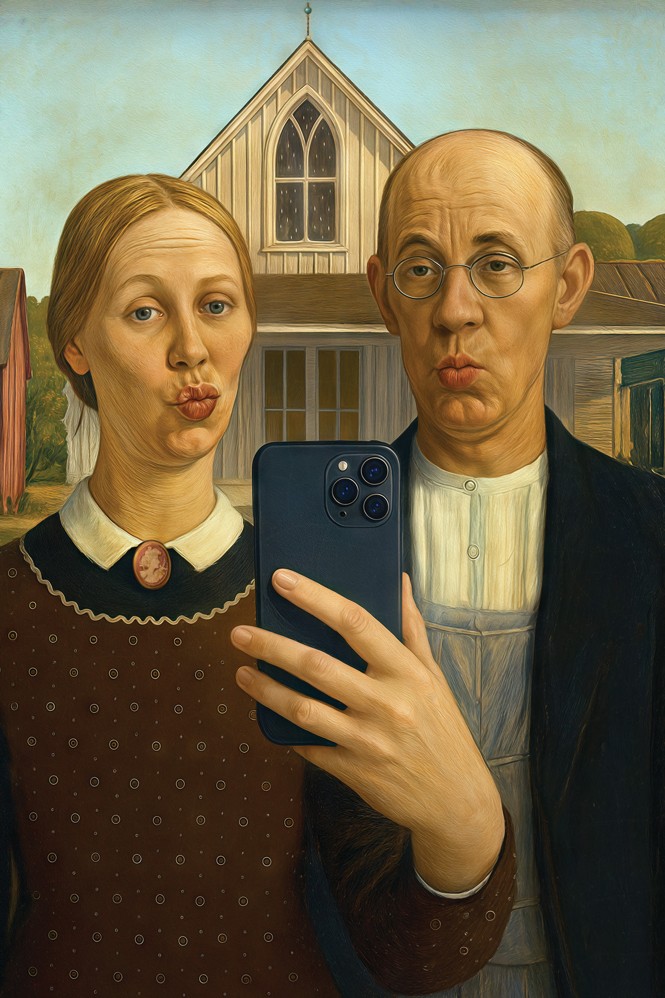

Think back to the summer of 2023, when Barbie and Oppenheimer both accomplished what the pandemic had seemingly made impossible: selling out movie theaters, and not for a superhero sequel. These could have been emblems of Hollywood’s intellectual bankruptcy, representing a glorified toy ad and yet another Oscar-baiting biopic. Yet the movies connected in large part because of their daring use of rhythm—visual rhythm, emotional rhythm, narrative rhythm. With hyperpop-ish glee, Barbie veered between musical, slapstick comedy, and melodrama. Its pursuit of constant stimulation didn’t just keep audiences rapt; the movie breezily conveyed weighty ideas about gender, consumerism, and even the meaning of life. Oppenheimer, about the father of the atomic bomb, was more quietly radical: The director, Christopher Nolan, told a complex story by montaging lots of vignette-like, TikTok-length scenes. Here was a sober, stately Best Picture winner whose hummingbird pulse felt stylish and modern.

Across culture, identity—Kissick’s bugbear—remains central, but its role may be changing: Forward-thinking, maximalist 2020s art is less about sorting people into tribes than about deconstructing now-familiar labels. The joyfully chaotic 2022 action-comedy hit Everything Everywhere All at Once—about a dimension-hopping Chinese American family—used a sci‑fi concept to complicate the category of “immigrant,” reminding viewers that any of us could have lived a million different lives. Meanwhile, Beyoncé has been making the boldest music of her career—which is saying a lot—by trying to expand popular ideas about Black music: first with the 2022 album Renaissance, a collage of beats linking hip-hop, Afrobeats, and house music, and then with 2024’s Cowboy Carter, a twisty-turny odyssey into country and rock. If audiences have become numb to moralistic messaging, they seem excited by works that use formal experimentation to capture messy truths.

The technologically induced isolation that Brooks worries about is also driving humanistic countermovements. The art of confessional songwriting is flourishing thanks to a wave of artists—Chappell Roan, Olivia Rodrigo, SZA—whose lyrical candor creates an intense sense of closeness between listener and artist. Together, these artists constitute an idea of “pop” that’s anything but generic; rather, it’s witty, specific, and vulnerable.

The leader of this class is, of course, Taylor Swift, who’s been pioneering a futuristic form of storytelling: every verse and every public utterance links together an intricate web of “lore,” which brings fans together for puzzle-solving and reinterpretation. Gioia, hardly the stereotype of a Swiftie, told me he watched the concert film about her records-smashing Eras tour three times. “I take some comfort in the fact that the biggest musical event of the last year was Taylor Swift, going on the road, playing real songs for real people in concert,” Gioia said. AI may be able to imitate Swift’s voice, but it can’t forge social bonds like she can.

A maximalist wave naturally favors the well resourced, and an actual renaissance won’t be possible until the economics of streaming are reformed or upended. Even so, indie artists are still releasing fantastical concept albums whose worlds spill out into music videos, TikToks, and other online channels (check out Magdalena Bay or underscores), and indie filmmakers are finding audiences for uncompromising visions (see the recent Oscars race between The Brutalist and Anora). Even seemingly brain-rotted content can sustain big ideas through inventive means: Internet comedians such as Psyiconic use costumes and visual filters to conjure bizarro characters that pop up in your social feeds, creating long-form satire out of snackable moments.

When I’m locked in and enjoying such highlights of 2020s culture, I’m grateful: Most of this work couldn’t or wouldn’t have existed before now. That doesn’t mean I’m immune to the dread that plagues the declinists. They’re really talking about forces deeper than culture: technological, political, economic, and social problems that require technological, political, economic, and social answers. The same YouGov survey that found Americans to be so unhappy with the state of movies, TV, and music found that people also generally feel that this is the decade with the worst economy, the least moral society, the least close-knit communities, and the most political division.

What art can do is remind us that our lives are not simply shaped by systems—they’re also a product of our own thoughts, inspirations, and relations. My favorite new TV show of this decade is HBO’s Fantasmas, a comedy created by the former Saturday Night Live writer Julio Torres. It’s a magical-realist depiction of a near future in which people live with bumbling AI assistant bots in housing complexes owned by corporations such as Bank of America. Torres’s character wants to make surreal films about animals, but is being pressured to cash in on his backstory as a gay immigrant. (A streaming service run by Zappos—yes, the shoe company—commissions a screenplay called How I Came Out to My Abuela.) This subject matter asks, quite darkly, whether the artistic spirit can survive modern life. But the imaginative way the show is rendered—in a dreamscape of interconnected skits, featuring handcrafted set decoration, performed by talents from today’s offbeat comedy world—offers a hopeful answer.

[Read: Fantasmas understands the absurdity of modern existence]

Culture is not just a map of the structures and forces that order our society. It’s what people make on top of, in between, in opposition to, and in collaboration with those things. We all have the power to listen more curiously, look more closely, and treat the present with the same sense of generosity that we extend to the golden ages of the past. When you tune in to the creativity that is still pulsing in these disorienting times, you can hear the story that most needs telling: Keep going.

This article appears in the June 2025 print edition with the headline “The Day the Music Died.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.