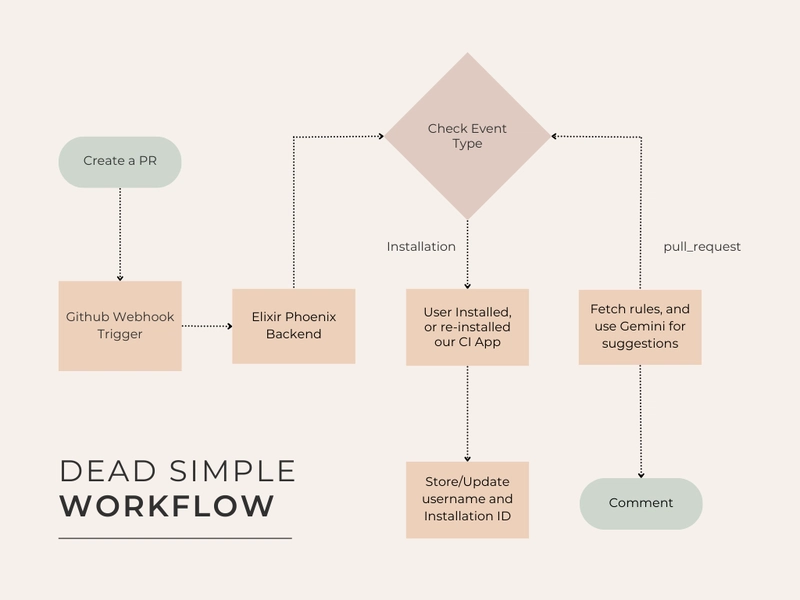

I was diagnosed with autism at 25. I graduated from college, got married, and became a published author.

My parents tried to get me diagnosed as a child, but because I was hitting all milestones I fell through the cracks. I'm now a dentist, author, and married.

Courtesy of the author

- In school, I didn't understand how my classmates didn't need a system to avoid panic attacks.

- My parents tried to get me diagnosed, but since I was a successful kid, I slipped through the cracks.

- At 25, I was diagnosed with autism and ADHD, and that didn't stop me from doing the things I wanted.

I've always sensed there was something fundamentally different about how I move through the world.

As a child, it felt like my classmates were speaking a different language, and I didn't have a hint of fluency. People would talk and interact, and connect in a way that felt impossible for me. I navigated adolescence with a sense of an outsider looking in on a hidden world, one I could interlope in at school but never fully belong to.

It wasn't until I was 25 that I finally got an answer.

I would have meltdowns every day at home

I didn't understand how my peers could experience and contribute to the complex noises and stimulation of a classroom when I would have near-daily meltdowns by the time I got home.

I couldn't comprehend that people didn't need to have a strict routine consisting of safe foods, clothes, songs, and smells when a single step out of my rigid system would induce panic attacks. It was absurd that others weren't obsessed with certain topics, gathering every tidbit of information with rabid hunger.

My parents also knew I was different and took me to psychiatrists. But, because on paper I was a "successful" kid, getting good grades and staying out of trouble, I slipped through the cracks — my symptoms were blamed on a panic disorder.

For a while, I was able to mask my way through life — I did ballet and cross country, graduated top of my high school and college classes, met my now husband, and hit "normal" milestones.

And then, in my first year of dental school, I suffered debilitating burnout. I wasn't sleeping, I wasn't eating, I was anxious and disoriented and nearly non-functional under the demands of my curriculum and living in a new city and being thrown into a dental school class filled with its own set of social rules I couldn't even begin to understand.

I was crumbling. If I didn't find help, I didn't know if I would make it to the next year.

I was diagnosed with autism and ADHD

Help came in the form of an incredible psychiatrist who, at the end of our first appointment, where I was a sobbing, broken mess, gently asked if anyone had ever suggested I'm neurodivergent. Fast forward a year, and at 25, I was diagnosed with ADHD and autism.

Getting my diagnosis was one of the most empowering moments of my life. At last, I had language for my overstimulation and sensory processing issues. I could acknowledge my unique wiring, and was told to explore and discover and free myself from trying to fit the mold of the neurotypical world. It felt like after an endless winter, I was finally able to push myself out of the soil and blossom.

I have since graduated from dental school, working as a full-time dentist focusing on making the experience as sensory-friendly as possible for my patients. I write books too. I leaned into my obsession with rom-coms and wrote my own featuring neurodivergent characters. One of my books, "Tilly in Technicolor," a young adult novel about an autistic boy and an ADHD girl grappling with the confusion of life after high school and falling wildly, beautifully in love with each other, but also their neurodivergent brains, went on to win an award. Another of my novels, "Late Bloomer" (this one adult and featuring autistic women indulging in a quiet, comfortable, romantic life filled with their special interests) is a USA Today Bestseller. Other titles in my backlist discuss anxiety disorders, CPTSD, and ADHD. I've traveled the world. I hate sports. I'm married and madly in love. I've cultivated friendships (mainly with neurodivergent folks) that young me would envy. My family seems pretty proud of me.

Recently, US Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., said autistic kids "will never pay taxes, hold a job, play baseball, write a poem, go out on a date. Many of them will never use a toilet unassisted. Autism destroys families."

I've done all of the things he said I wouldn't. For all intents and purposes, I am an accomplished individual. But this list of things I've done doesn't actually matter. I, like all disabled folks, am more than my output, more than a taxpayer and employee. My diagnosis made me realize that I don't have to conform to a set of societal expectations to "earn" a worthy existence.

I have value simply for existing, just like everybody else.