How to test for and control bird flu before it’s too late

If rapid tests can be employed on a mass scale, H5N1 bird flu outbreaks can be much more easily controlled.

If there was one thing we learned from COVID, it was the need for rapid, accurate, point-of-care testing to help contain the virus before it had spread silently to many others. It was years before we had these effective tools and could properly apply them in real time to real patients.

Today, the same problem exists in animals for H5N1 bird flu, where the virus spreads through flocks before we know that even a single bird is infected.

It takes several hours for the results of a polymerase chain reaction test, which “detects genetic material from a pathogen or abnormal cell sample,” to come back. By then, the only effective strategy is often culling all the birds in the flock to hopefully prevent the spread beyond it.

With over 1.5 billion chickens in the U.S. at any one time, there are a lot of birds coming in and out of farms. The latest bird flu outbreak, which has persisted in the U.S. since 2021, involves over 168 million poultry.

At the same time, the majority of new detections are in small backyard flocks and live bird markets. Genetic studies confirm that the virus is being introduced repeatedly from wild birds.

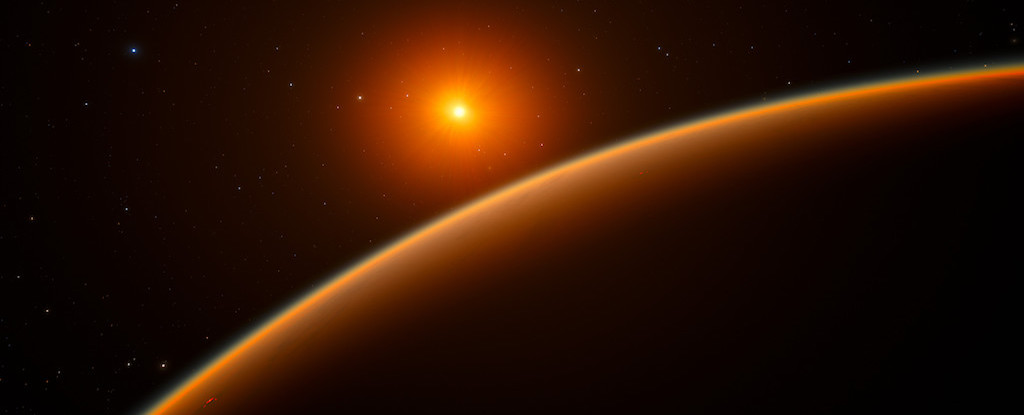

Waterfowl and shorebirds are the natural hosts for avian influenza viruses, though it often doesn’t make them very sick. There is simply no way to limit the spread among wild birds or the spread from there to poultry.

Wild birds migrate in large numbers to the U.S. in the fall/winter when the weather is cool and wet. Migration back in the spring leads to further exposure.

Vaccinating wild birds for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza is not an option. Estimates suggest there are 50 billion of them. You could never catch and vaccinate enough of them to have an effect.

Large-scale production facilities try to limit their poultry's exposure to wild birds. Trucks are cleaned thoroughly, boots are dipped in disinfectant on entry and exit and screening and special doorways keep wild birds out.

Poultry houses are thought of as “barrier facilities” where, once inside, the birds can be kept healthy and isolated from risk. In contrast, it is very difficult for a homeowner with a backyard coop to avoid any kind of exposure or contact with wild birds.

Influenza is transmitted directly by droplets in the air and also indirectly by contaminated surfaces. Backyard poultry can be infected from water or food bowls that have been contaminated by wild birds.

Once infected, over 90 percent of chickens and turkeys will die from this virus. The virus incubates for several days before birds show symptoms, so it can’t be managed by removing only the birds that look and act sick, because by that time, it has already spread through the flock, resulting in either death or culling of a large number of birds.

More attention is being paid to vaccinating poultry with bird flu vaccines before a flock is infected. Dr. Jarra Jagne, a poultry veterinarian at Cornell, told us that “killed or inactivated H5 vaccines are used around the world,” and companies in the U.S. are developing and testing new versions for this outbreak. The USDA is offering grants to incentivize their rapid development.

But to keep the business profitable, poultry vaccines need to be highly economical, because of the number of birds involved, their short life span (layer hens live less than two years and each new group needs to be vaccinated) and the low cost of each animal.

Another major obstacle to vaccinating poultry is that the antibody tests that many countries use to look for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza are often unable to distinguish a sick bird from one that has been vaccinated. The National Chicken Council estimates the export chicken market to be over $5 billion per year, and some countries simply won’t accept imports from countries that vaccinate.

But according to Dr. Laura Goodman, an expert in molecular diagnostics at Cornell Public Health, the new rapid tests which are in the process of being developed to only be positive for H5N1, could then be used before chickens are showing signs of illness and before they are introduced into a barrier facility or a live bird market.

If rapid tests can be employed on a mass scale, H5N1 bird flu outbreaks can be much more easily controlled. The tests can also be used to demonstrate that entire flocks remain uninfected and more traditional PCR tests can be reserved to screen for new subtypes that may be emerging.

The goal of controlling bird flu via rapid molecular testing goes well beyond protecting hens, their eggs and our economy. Because, as the viruses spread and mutate, they may adapt to more and more species, including humans.

Alexander Travis VMD, Ph.D., is chair of Cornell University’s Department of Public & Ecosystem Health, director of Cornell Public Health, Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine, and organized Cornell’s Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Resource Center. He is the co-founder of TETmedical, Inc. Marc Siegel, M.D., is a clinical professor of Medicine and medical director of Doctor Radio at New York University’s Langone Health.