How Does Agency Shape Education? | A Conversation with Charles Fadel

Exploring AI's role in education, agency's importance, and school missions with insights from Charles Fadel and Tom Vander Ark. The post How Does Agency Shape Education? | A Conversation with Charles Fadel appeared first on Getting Smart.

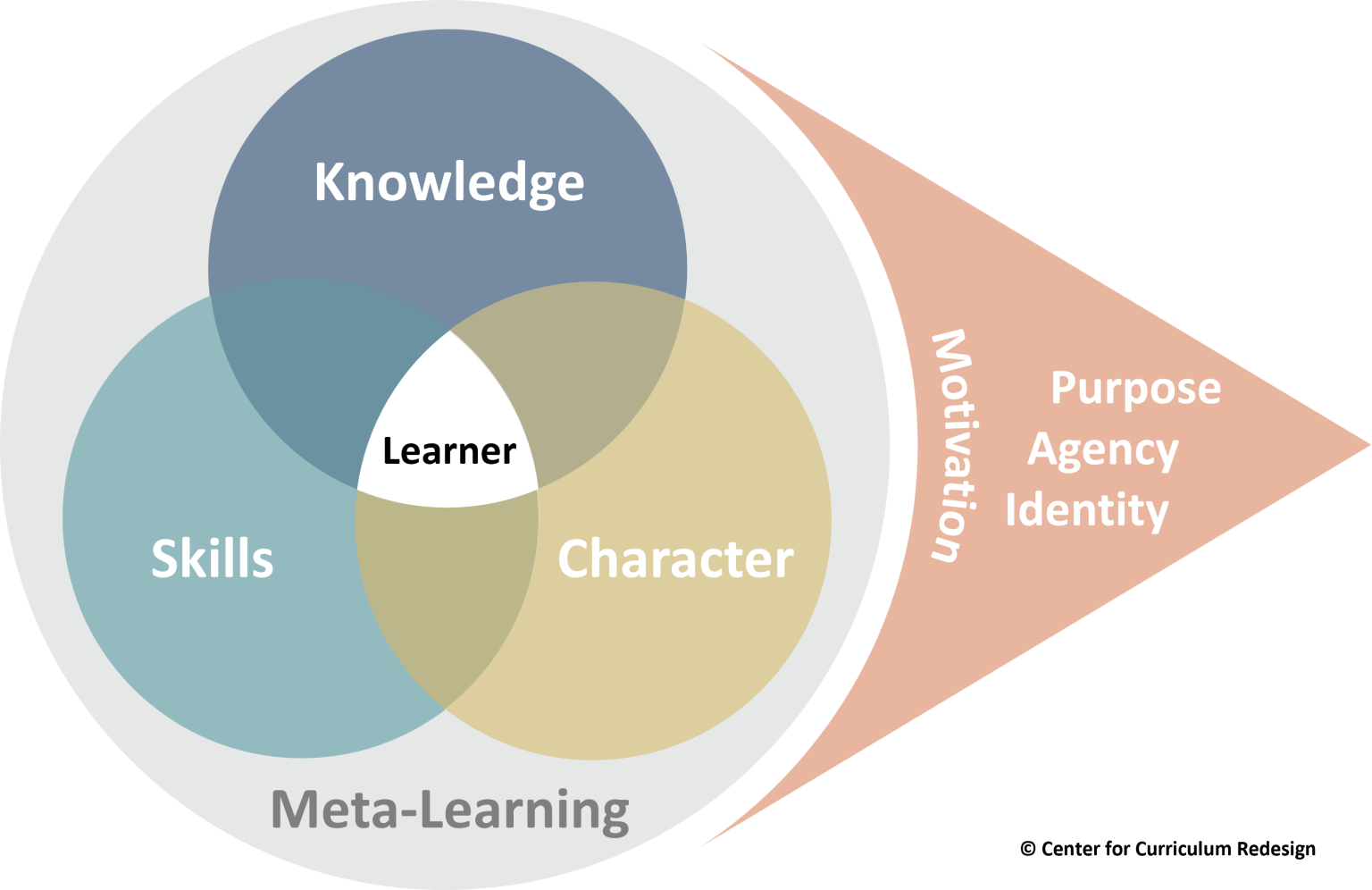

Last year, we did a deep dive on education in the age of AI with Charles Fadel, unpacking a beautiful framework that highlights a set of skills, character traits, and meta-learning, applying a modern emphasis to each one of them, effectively updating them for the AI age. Today we’re talking about agency, a driver throughout Fadel’s framework, which he defines as a combination of curation and purpose—two things that we’ve been discussing at length at Getting Smart, and two of the design principles for our new Pathways campaign in an age of abundant content and information.

The curation of taste —how you spend your attention and what you trust—is more important than ever. At the same time, people who are emboldened and empowered by purpose will thrive in an age of smart tools. A few leading experts have recently said that with agents and reasoning engines, agency just became more important than intelligence. And unlimited access to global expertise means that the ability to leverage that expertise will be more important than being the expert. Today I’m joined by the one and only Tom Vander Ark and returning guest Charles Fadel, founder of the Center for Curriculum Redesign, who’s returning to take a look at what has changed and what it means for learners.

Charles, Tom, thanks for being here.

Outline

- (01:36) The Evolution of AI and Its Surprises

- (04:35) Debating Agency vs. Intelligence

- (08:58) The New Mission of Schools

- (11:26) The Role of Knowledge and Competencies

- (19:33) Challenges and Opportunities for Teachers

- (20:31) Cognitive Offload and Meta Learning

- (25:03) Building Adaptability and Self-Directed Learning

The Evolution of AI and Its Surprises

Mason Pashia: Charles, so you were working on this book in the early days of AI becoming publicly visible, I think a lot of people finally encountered AI, but it had been around in some form for some time before that, and a lot has changed since then. So what is new and different in this moment, and what’s surprised you over the last few years, if anything?

Charles Fadel: We started our first colloquium on AI back in 2014, and there was a preceding book in 2018 called Artificial Intelligence for Education. So we’ve been prepared for this. The big surprise has really been how foundation models have taken us from narrow bounded problems like Go or strategy games and generalized that to a much broader set of capabilities because it’s not trained on just Go or chess. It’s trained on the entire internet. So that happened faster than I would have expected. But of course, when things advance this fast, people sometimes go all the way to the other side and say, “Oh my God, now we’re gonna have AGI in five years.” This is where I spent the past year trying to figure out exactly where this balance will stabilize for a while.

You see it in this phase because we’ve gone from the science phase to an engineering phase. We have all sorts of capabilities coming on board simultaneously, whether it’s refinements of training or better datasets, verticalized datasets, etc. This is what I call the engineering phase of AI. Although it’s not AGI and it won’t be AGI for quite a while, this is still quite fascinating and quite powerful. I’m afraid people get lost in this dichotomy of either it’s AGI or it’s not useful. No, it’s incredibly useful even in today’s capabilities.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Go ahead, Tom.

Tom Vander Ark: Charles, for me, it does feel like we passed a really interesting and important threshold in the last 60 or 90 days with the widespread access to agents, operators, and particularly reasoning engines. The reasoning engines have been an interesting development where just by giving a little extra time to an LLM, you can see chain of thought logic. In short, these new reasoning engines, often called deep researchers, are like everybody having a group of postdocs in your back pocket and access to that level of expertise. Moving towards access to capability where expertise is put into motion on a defined mission feels like an interesting threshold. I really wanted to know if you buy C. Carr’s notion that agency is now more important than intelligence.

Debating Agency vs. Intelligence

Tom Vander Ark: You called out agency as being one of these key new drivers, but do you buy Carr’s argument that agency is now more important than intelligence?

Charles Fadel: Generally, I don’t buy these dichotomies until they’re well in. It’s relatively easy to make large claims like this when you’re raising a lot of money for new things. I get it. But I’ve always tried to be where the reality is. So certainly very important. Is it more important than intelligence or not? Who knows? That’s a big statement. But taking us to why agency matters so much—obviously, if you have engines with all these capabilities, what you do with them, how you drive them, and to what purpose, as Mason was saying earlier, matters greatly. And this is not going to surprise you, Tom, because you wrote about this a few years ago about what a high school would look like even without AI. We were already seeing the need for this sort of capability.

I want to also answer Tom’s questions regarding reasoning and so on. I don’t want to minimize what an engineering phase is. The engineering phase is potent and what improvements like that. Remember in the earlier days we would literally tell via prompt the LLM to take its time to give an answer. Now it’s incorporated into taking its time. It’s what I would call an incremental improvement, even though the result is quite fascinating and really powerful. It’s just an engineering tweak. It’s not like we came up with a new algorithm or something. Nevertheless, reasoning is certainly important, but then I started asking myself and my AI experts around me, saying, “Hey guys, why would I care about a GPT-4 if I can have all-in-one?” And they said, “Probably not for long.” And we were right. They’re just merging the whole thing because why would I care about a non-reasoning engine? Everything should be reasoning, quote-unquote, as basically better results that it is giving me. Now, the aspect of going into deep research, that’s a different story because now this reasoning is taking into, let’s say, the depth of a specific question. And there, of course, a solid 80/20 rule applies, meaning you are not going to get the true experts. You’re still going to get 80% of that expert. The difficulty is the hallucination rates. Where’s that 15% or 30% on a bad day in what that expert is telling me that I cannot believe or I cannot trust because I have no idea? I’m not an expert in whatever biology this or that. So what exactly am I supposed to reject if I don’t have some level of expertise myself? And that’s something we have to be wary about in our conversations here. Is an 80% expert good for all situations, or just the ones that are not very critical?

Mason Pashia: Yeah, I think that’s super important. So that may adjust the statement to say agency is as important as intelligence in some ways, maybe more than more.

Charles Fadel: Even knowledge, basically what you were saying, is that knowledge still matters. For sure. If you have no idea about whether it’s a bit like dealing with your lawyer or your financial advisor, you have to know just enough to be able to ask the tough questions. If you don’t even know that much, you’re snowed. So you’ve got to know, where are the corner conditions of what you’re asking?

Mason Pashia: Yep. I feel that way every time I go to the mechanic. I don’t know any questions to ask.

Charles Fadel: Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

Mason Pashia: So I am wondering, all this being true, if we have knowledge being as important as ever, we have intelligence, we have agency, and we have this kind of expert, global expert in our pocket all the time now.

The New Mission of Schools

Mason Pashia: What is the new mission of school then? And is it new? Is it the same mission it’s ever been with a couple of tweaks, or are we actually entering an era where we have a new mission for what school should do for learners?

Charles Fadel: It’s really a question of phases, right? This phase right now, which will last, I don’t know, five to ten years until AGI, is a different animal than what will happen with full-blown AGI. It’s hard to discount that full-blown AGI is not gonna happen by 2040. Although one has to be really clear here, it’s still dependent on whether we have breakthroughs on the neurosymbolic side. It’s not gonna happen just by scaling or just by inference processing or whatever. We’re gonna need new algorithms. And so that’s the neurosymbolic side, which DeepMind tries to use, but the rest of the industry is somehow ignoring because it’s taking us back to the 1980s logical processing à la Marvin Minsky and so on. And this has bifurcated. We have the two tribes that have bifurcated away from each other. They need to come back together for logical processing to work with LLMs—that’s neurosymbolic—and that’s gonna be a while, and you cannot predict breakthroughs. That said, in the next 10 to 15 years, we have enormous capabilities at our fingertips.

So what’s the mission of the school? The mission of the school is a babysitting function. What are you gonna do with your kid every day? Let’s admit it, it’s necessary. Secondly, it’s gonna be preparing that kid for some form of purposeful life. For the time being, a purposeful life includes but is not limited to jobs. No one is talking about jobs utterly disappearing. People are talking about jobs being impacted, augmented, whatever, etc. Plus, we also have the new slew of jobs that we didn’t even consider, didn’t even realize could emerge, that emerged. For instance, would you have thought of influencer being a job at the very beginning of the internet? Not quite. And yet, here we are. There’ll be new jobs. There’ll be some jobs that will be partially whacked, etc. So we’ll see where that lands.

The Role of Knowledge and Competencies

Charles Fadel: So that means that education is still about giving you a toolkit for jobs and life. That toolkit needs to be educated. You’re not gonna have your child sitting at home with VR goggles, playing games, and then by age 20 magically say, “Okay, now I can use AI.” You need to scaffold that kid and scaffold the kid much better than we have done in the past. So it means you still need knowledge, but now that pyramid of knowledge gets different. Rather than having mostly declarative, meaning memorization, and procedural knowledge, meaning how to run equations, you’re also gonna need conceptual and epistemic knowledge. Meaning, what is the concept behind what I’m learning? For example, in history, a concept would be geography is destiny. In exponentials, the concept would be deceiving, then explosive. You’re gonna need to understand the depth of that rather than just the procedural aspects. And then you’re gonna need to understand the epistemic of the discipline. Why do I use mathematics to solve this kind of problem, and how do I do so?

Now this pyramid of knowledge has become a trapezoid. So that’s a key improvement. And then you have to embed all the competencies we’ve talked about—skills, character, meta-learning. And then you have to make sure that as you drive the student’s personalization, you pay attention to their belonging and identity, their agency and growth mindset, and then their purpose and passions. So it’s not massively different, but it’s incrementally ambitious. As I say, it’s not radical. The proportion of projects, for example, would have to increase significantly during the outer years, let’s say high school, etc., to make room for the latitude for students to exercise their agency and purpose.

Mason Pashia: Definitely. Tom, that’s your wheelhouse. What would you add?

Tom Vander Ark: I just want to underscore that last phrase of school as a place to exercise agency, identity, and purpose. I guess to develop and exercise that. I just want to note what a profoundly different conception of school that is, at least in part, including the other functions that Charles mentioned. It’s a bit of an overstatement, but I listened to Seth Godin’s What is School For podcast. You remember that from 10 years ago? He’s updated it and re-released it. And in there, he does a simplified but somewhat accurate description of how we got the schools we have, which are very much the opposite of supporting identity development, purpose development, and agency development. They’re all about compliance and, to some extent, knowledge accumulation. And so Charles is describing a purpose of school that I think is radically different than really the point of the dialogue I wanted to have today. In this regard, Charles, I guess I’ve begun to think about school, particularly high school, as the on-ramp to augmented contribution. We’ve already thought about high school and college as preparation for work and citizenship, right?

Mason Pashia: Yep.

Tom Vander Ark: And my sense is that the two things that have changed are that we can now, at least in a progression from elementary to secondary, think about augmented intelligence, augmented agency. This is Reed’s conception of super agency of Homo TechNet of being the tool-building. I think there’s a new opportunity to create a sense of possibility about what I can do with smart tools. Absolutely. So that’s one. And then the second part of this is to earlier shift from preparation to contribution or to step into value creation, both in the enterprise sense of that and the civic sense of that word, and to do so with smart tools. And so that’s a different way to think about school, of moving into contribution using smart tools for the purpose of creating value for your community.

Charles Fadel: Yep.

Tom Vander Ark: Charles, one of the most important lines in your last book was “Entrepreneurship is the new job.” And I think with the layoffs that we’re seeing and the slowdown in hiring that we’re seeing, the number of new starts, business new starts, I think we’re at the beginning of seeing your prediction really come true. And authority, your prediction, this idea of entrepreneurship is value creation.

Charles Fadel: Yes.

Tom Vander Ark: And so I’m thinking about that for me as the new updated purpose of school. That it’s an on-ramp to amplified, augmented value creation in both the enterprise and civic spheres.

Charles Fadel: Yes, totally agreed here. The difficulty is that it’s not just one aspect, right? It’s several things that need to happen, right? And so we’re talking about, for example, high school being less specialized than ever because if you specialize too early, you may be stuck in a dead end. And actually, even the same for college. Who knows whether in 15 years you’re gonna have to be a painter, a physicist, a poet, or a physician, right? And so that means you need to have that T-shaped person even more. Yes, the bar of the T needs to be going on for even longer before you start specializing. We overspecialize too early in high school already, so there’s so much optionality. So this is gonna sound contradictory. On one hand, there’s a lot of optionality, which would say that’s good for agency and purpose, but on the other hand, why would anyone graduate without social sciences? If knowing yourself and others matters so much nowadays, we should all take psychology and sociology. If entrepreneurship is the job of the future, how come it’s just an option for some schools some of the time? It should be mandatory. Same thing for technology and engineering. If T and E matter so much and we keep only talking about STEM but teaching M and S, that means yes, some of the older things have to go and have to be reformed to make space, and that’s the hard part. So that’s just talking about one aspect. Then you have, from a pedagogical perspective, now what do I do? I have these amazing tools at my disposal, and as I’m doing my projects, I can now ramp up its sophistication. And so sure, I studied data science in math, but now I have this Google app, which I forget the name, I saw it yesterday, that allows me to do a lot of data science in a box. Okay, I gotta make sure it knows what it’s talking about due to the hallucination problem, etc. So it forces me to be even better in a sense of understanding the limits of the tool that I’m using and understanding enough data science to know where it has gone wrong. I have to be able to sometimes retrace those steps, and that’s really a meta capability that we’re asking for a student to develop. And that means a lot more time needs to be spent on not just the procedure but on the concepts and the epistemic so that they can retrace those steps.

Challenges and Opportunities for Teachers

Charles Fadel: So all of this says the sophistication of what’s required in a classroom is so much higher, it’s gonna get so much higher that it’s gonna really put a lot of pressure on the teachers to figure out how to adapt to all of this. And it’s unfair what we’re asking the PE teachers to do is unfair because no teacher has the time to jointly essential content, core concepts, competencies, formative assessments, project-based learning, agents helping, all of that, etc. So we’re gonna have to rethink what the role of the teacher is. And it’s not at all a dig on their capabilities. No. It’s just that the needs have become superhuman.

Tom Vander Ark: Thank you for that description. That’s really provocative and important. I want to address it again as we think about possible school models.

Cognitive Offload and Meta Learning

Tom Vander Ark: But I do want to underscore something that you address in your book, which is cognitive offload. You talked about the role of the teacher. The challenge that I observed in schools last week was using gen AI for cognitive offload to get, yeah, to get the machine to do the hard part, the harder learning.

Mason Pashia: Yeah.

Tom Vander Ark: And in fact, we want to invite students to do that. You’ve done a really nice job of saying the goal now is maybe not just doing the writing or the coding, but the editing. That we step up into meta learning, we step up a level and become an editor, a curator. Is that notion of editing and curating part of the solution for avoiding cognitive offload because we’re inviting students to do bigger, harder work at a different level than we’ve done before?

Charles Fadel: Exactly. Cognitive offloading is, in psychology, it’s also called cognitive miser. Our brains are cognitive misers because of evolution. They are 20% of our energy consumption for 3% of the mass of the body. So they’re an inherently expensive organ to run. And so it tends to go on autopilot as often as it can. Throughout evolution, it has served us perfectly fine, and even today it serves us perfectly fine. We make a lot of judgments in a snap because we don’t want to expend the energy to rethink every single thing we do during the day. Makes sense? Unfortunately, it means that it’s also lazy by good evolutionary design. And so combating that laziness is a constant effort. It’s the same as combating, for example, the anthropomorphization we see out of AI. Yes. Every time I talk to one of these engines, I gotta remind myself it’s an “it,” dammit. It’s not a he or she or whatever, or they. It’s an “it.” And that’s really the hard part—constantly monitoring yourself, so you actually force yourself to think and consider it a good thing, even if your brain and your energy consumption say no. Please don’t make me think. You see that in social media. No one wants to actually think, and people want just to emote. And so reigning yourself in, reigning that emotion in, and forcing yourself to think is a constant struggle for humans, and it’s only gonna get worse. So yes, that can be trained in school. A very quick example is, okay, we have to write an essay. I know full well the AI can write perhaps a better essay than me, perhaps. Okay, let’s do the following then. No screens. Students, write your essay. Okay, now write an essay with your AI. I want to see the prompts that you’re gonna be using, and I’m gonna see how you’re gonna evaluate that essay. Now you force the student to go to another level in understanding what an essay is for. And that’s exactly the meta level that we were discussing.

Mason Pashia: And well, by the way, hopefully, the student will also come back and say, “Why did we need an essay in the first place? We could have done better with a video or something.” That would be really wonderful as an answer.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, I love that. In the meta-learning section of your framework that you put out in this book, you talked about metacognition and meta-emotion, and the two emphases, the modern emphases for those, are adaptability and self-directed learning. This past week, I was at a digital credentialing summit and I heard a couple of things that really just enforced this. Some of them are a little bit blanket sweepy, but still worth stating. So one of them is that the lifecycle or the lifespan of technical skills going forward is gonna probably be two years before they need to be reevaluated and reapplied. One is that 65% of an employee’s job will change every five years—five to seven years was the metric. And then one of the keynoters reframed the five-day workweek to a four-plus-one week workweek, where four days are for work and one day is for learning. So all of these things are this idea that self-directed learning and adaptability are going to not only be a superpower but they’re going to be a necessity basically for thriving in the future marketplace. And I’m curious. One, how you react to that. And two, how do we design learning environments for adaptability?

Building Adaptability and Self-Directed Learning

Mason Pashia: How do you actually create a learning experience that emphasizes building the skill of adaptability?

Charles Fadel: Two very big questions. So the first one regarding the four-plus-one—for me, it’s really five-plus-two. I spend all my weekends learning. I don’t have—I’m lucky that my daughter is old enough now and I don’t have to worry about that. But for a parent, how the heck do you do that? And I don’t see any corporation giving you a full day of training for free. Come on. It’s a joke. They make you fill in those, “what am I gonna learn this coming year?” and they don’t give you a budget, and then they expect you to learn it on your own time. So that’s gonna be an interesting thing to deal with. That aside, I completely agree that we have to constantly keep on learning by ourselves, and it’s no longer a choice.

Now, that said, there are things that are more or less invariant, even in a discipline that’s as fast-changing as computer science. And this is something that’s sometimes misunderstood. There are plenty of things in computer science that go back to the ’50s and ’60s, such as the structure of how you think logically. If-then-else statements and so on, that hasn’t changed. What revolves constantly is which language do you use? Is it Java, is it Python, is it R, is it this? Heck, I had to learn it in Fortran. That’s how things change, and that’s the fast-changing part of computer science. But the fundamental principles, those concepts we talked about, the meta aspect of, the epistemic aspect of computer science, those are far less variant. So we have to think more carefully about what changes and what doesn’t. So that’s one.

Second, regarding how do schools teach adaptability and self-directed learning, that is even more important, of course, in higher ed. Because now you are launching the student and you have no idea where that’s gonna go. They’re launching on their own. If they haven’t learned by then to learn by themselves, they’re not gonna have an easy future. So it’s an attitude that has to be imparted along the way. Adaptability can be more than an attitude. Adaptability can be specific disciplines and specific actions you take to force you to be adaptable. And that’s something I’m working on quite a bit right now to exactly discern what makes you adaptable. And so my first findings are intriguing because they’re not the sort of things that you normally see. For instance, sailing, you have to deal with temperature, wind currents, etc. My wife is a great sailor, and I discovered that through her, and oh my God, what a mess it is. Okay. Martial arts—not the martial arts dojo, where everyone’s polite with each other. No, we’re talking about street fighting sort of thing, where you are crossing a mountain torrent and you have three bulky guys coming at you, and now you have to do something. So putting you constantly in unexpected situations which are very uncomfortable, and at some point, you develop the confidence that, “You know what? I survived the thing in the mountain torrent, and I survived the storm in my sailboat, and I’ve acquired the confidence that whatever life throws at me, I’ll figure it out.” And some people are like that; they’re confident that they’ll figure it out. And that’s really the end goal here. How can we make sure that the students are confident to figure it out? Not a fake self-confidence, not an empty self-confidence, but a self-confidence of having gone through, walking on hot coal or whatever. All sorts of strange things you would do to build that adaptability and self-confidence.

Tom Vander Ark: Mason, I’ll just underscore that the skills that Charles just described are, many people would say that those are the beginning of the early skills of entrepreneurship. It’s opportunity recognition and problem finding. It’s identifying, naming, and framing a problem worth working on, in this case because it’s life-threatening. And I also want to underscore how different a learning environment is that invites those kinds of skills. It is the opposite of a master schedule, the bell rings exactly every 48 minutes, that’s focused on compliance. You at least periodically need opportunities to step in a radically different context. One that’s disorienting and challenging, maybe even threatening. And you get, you have to have reps at that set of skills in order to build that adaptability muscle.

Charles Fadel: Yes. So you’re totally right. Now, of course, you want to build that confidence in the student little by little. So fail safely at first and then move on and move on. But even in the bell-ringing, all-scheduled aspect, you can introduce a lot of randomization. “Hey, 50 minutes are passed. The bell hasn’t rung. Oh, it’s a two-hour session. I was not prepared for it, but, oh, roll with the flow. You roll with the punches.” Or, “What? It’s not a math class. I had prepared for a math class. It’s a history class, and we have a quiz. Oh, go with the flow, whatever.” So even with a school schedule, you can tinker around to make that unpredictability there and accept it like, “Eh, whatever. Another crazy thing they want me to do, whatever.”

Mason Pashia: It’s starting to sound like schedule roulette there, Charles. That’s a wild wheel that you’re spinning.

Charles Fadel: Within reason, and you can increase the amount of randomization over time. Totally right. You don’t want the last thing you want with a young child is to make everything unpredictable around them. On the contrary, they have to be extremely protected and nurtured to have a stable base. But once that stable base is established, in primary school, then little by little in middle school, you start increasing the unpredictability. You don’t want to mess them up by being constantly unpredictable. It’s like waking your cat up all the time without warning for no reason. It is gonna go cuckoo on you.

Tom Vander Ark: Mason, I know you wanted to ask us to think about what the future of school looks like. I want to go back to a comment that Charles made earlier about the T-shaped professional and being systematic about breadth. One, I just want to acknowledge that it’s really important and challenging if you’re trying to be student-centered and value-interest-driven learning. If you’re really committed to the value of breadth, then you really do need an environment that is somewhat systematic about exploring possible futures. So I wanted to call out Coone Valley and their, we think they have the best career education in the world, and it’s because they, between kindergarten and 12th grade, they explore about 72 possible futures. And they’re systematic about putting kids in very different immersive experiences and then inviting them to reflect on those experiences. So they are systematic about exploring possible futures. And I think that’s an example, a specific example of what, if you’re committed to this T-shaped professional of both breadth and depth, you do have to be systematic about inviting kids into a variety of experiences. It’s also a way that you can build adaptability because you’ve been systematic about dropping them into very different sets of contexts where different kinds of problems are framed in different ways.

Charles Fadel: Very good point, Tom. Yeah, absolutely. And it may seem that this imposition is counter to the spirit of agency, but it’s not because you can have agency within the constraints, meaning let’s say everybody has to build a robot, no choice. However, Tom may decide to build a marine robot, and I’m gonna build a flying one, and Mason is gonna build a crawling robot. And our teacher then is gonna ask us, “Okay, fine, you are, this is your agency. What purpose do you have for your robot?” So Mason’s gonna say, “I’m gonna remove mines.” I’m gonna say, “I’m gonna help crops.” Tom’s gonna say, “I’m gonna count plastic particles in the ocean.” That’s how we have aligned agency and purpose within a certain imposition. Yeah. We give choice within imposition, not just completely freewheeling choice. Now that said, you’re also gonna have blocks of time in high school where you do have personal projects, no questions asked. Do whatever the heck you want. And group projects, same thing. But within a given discipline, you can also show how you can impose a discipline and yet leave room for agency and purpose.

Guest Bio

Charles Fadel

Charles is a global education thought leader and futurist, author, and inventor, with several active affiliations. His work spans the education continuum of K-12 schools, higher education, and workforce development/lifelong learning:

- Founder and chairman of the Center for Curriculum Redesign (CCR) in Boston, MA. CCR focuses on “Making Education More Relevant” and answering the question: “What should students learn for the 21st century? In an age of Artificial Intelligence.”

- Chair of the Education Committee of the Business and Industry Advisory Committee (BIAC) to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), nominated by the U.S. Council for International Business (USCIB). He works with several teams at the OECD, most notably Education 2030, PISA, CERI, and the Expert Group on AI Futures.

- Senior Fellow, Human Capital at The Conference Board

- Board member at the United States Council Foundation (USCF).

Through his 25-year high-tech career, he personally experienced the disruptive effects of exponential change. This invaluable firsthand knowledge allows him to offer a unique perspective to the world of Education.

Links

- Education for the Age of AI

- Portrait Model | Getting Smart

- Center for Curriculum Redesign

- Cajon Valley

- Podcast: Education in the age of AI with Charles Fadel

The post How Does Agency Shape Education? | A Conversation with Charles Fadel appeared first on Getting Smart.

_Sergey_Tarasov_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)