Gender-based care for children should be based on science, not partisan whims

There is a deep partisan divide on pediatric gender medicine in the United States. A new review from the Department of Health and Human Services could offer a new way forward.

There is a deep partisan divide on pediatric gender medicine in the U.S. Republican-controlled states are banning the use of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and surgery on minors with gender dysphoria. Democrat-controlled states are declaring themselves sanctuaries and protect access to these same treatments.

The Democrats face two problems. One is that their position is not politically popular. A New York Times Ipsos poll found that 71 percent of all Americans, including 54 percent of Democrats and Democrat-leaning respondents, believe doctors should not be allowed to prescribe puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones to patients under 18.

A second problem is that, even if Republicans are not consistent supporters of science, science supports the Republican approach to pediatric gender medicine.

Countries such as Finland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Norway, which have looked at the scientific evidence, have all restricted access to cross-sex hormones and puberty blockers. While these restrictions fall short of the total bans proposed by Republicans, they go much further toward that than anything Democrats seem prepared to consider.

In this context, a literature review, which the Department of Health and Human Services is set to publish as soon as today, could offer a way forward.

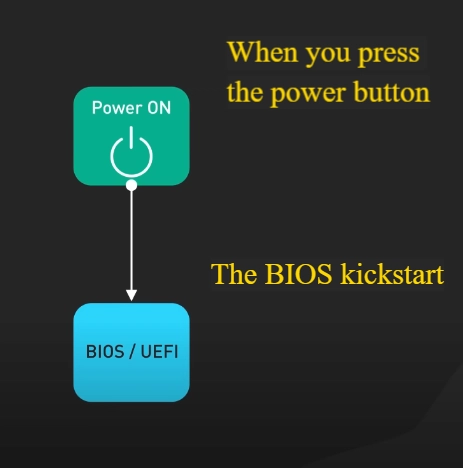

The review, which was directed by President Trump’s Executive Order on Protecting Children From Chemical and Surgical Mutilation, will examine best practices for promoting the health of children who assert gender dysphoria, rapid-onset gender dysphoria, or other identity-based confusion. Best practices in health care today means evidence-based practice.

Evidence-based medicine was developed to overcome the shortcomings of the traditional consensus-based or good-old-boys-sitting-around-a-table model of clinical guideline development, which is prone to bias. Doctors, however eminent they may be, are still human, and tend to cherry-pick studies that support their favored treatments and ignore unfavorable evidence.

Evidence-based medicine attempts to eliminate or manage bias through systematic reviews, by which research on a medical treatment is selected and evaluated according to pre-determined rules. The evidence for the harm and benefit of a treatment is then rated as high, moderate, low or very low certainty. This evidence is then used to develop treatment guidelines.

The main documents that currently support what are known as "gender-affirming" treatments in the U.S. are the Endocrine Society guidelines, the American Academy of Pediatrics Position Statement and the Standards of Care of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. The Cass Review in the United Kingdom found that none of these documents are trustworthy, evidence-based guidelines.

The only guidelines that the Cass Review found to be evidence-based were from Finland and Sweden. Both recommended that psychotherapy be the first line of treatment for children and adolescents with gender dysphoria, and that puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones be provided only in a research setting.

Supporters of these treatments object that evidence-based medicine requires randomized control trials, which they claim are not feasible for puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. Although it is true that randomized controlled trials provide the highest certainty evidence that a treatment is effective, they are not essential to produce an evidence-based guideline. What is essential is that the strength of the recommendations reflects the strength of the evidence.

The problem in gender medicine is that treatment guidelines and doctors make strong recommendations in favor of puberty blockers and cross sex hormones on the basis of low- or very low-quality evidence. Young patients and their parents are being told these treatments are safe and effective when all the evidence shows is that some people may benefit, some may not and some may be harmed.

Both doctors and transgender activists often go further and claim that these treatments are life-saving, since patients are at risk of suicide if not allowed to transition. In some states, child protection agencies have the power to take children away from parents who refuse to agree to medical gender transition.

Democrats have tried to avoid the debate on the evidence for bans on these treatments by objecting that bans constitute political interference with the practice of medicine. However, medical practice has been subject to political control for more than a century. Doctors and other health care professionals need to be licensed by state medical boards. Drugs need to be licensed by the FDA before they can be prescribed.

The regulatory system has broken down in gender medicine because of political pressure. It was presented as a human rights issue rather than a scientific issue. Activists pushed for changes to clinical guidelines and practices that made gender-affirming treatments available at younger ages and with less preliminary assessment. The usual processes of scientific research and academic debate were ignored. Clinicians and researchers who expressed doubts were labelled "trans-phobes" and sidelined.

This process happened mostly through the internal politics of universities, medical associations and journal editorial boards, shielded from public scrutiny. One instance did become public, however, when documents disclosed in the Boe v. Marshall case showed how former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Health Rachel Levine had pressured the World Professional Association for Transgender Health to remove minimum ages for most forms of medical transition from the eighth edition of its Standards of Care.

Meanwhile, doctors who question the consensus have limited ability to work for change through their professional associations. Dr. Julia Mason found this out when her resolution was blocked calling on the American Academy of Pediatrics to conduct an evidence review of its position paper on gender-affirming care.

The forthcoming HHS review could provide an opportunity to move the debate on gender medicine away from partisan politics and back to science. It remains to be seen whether the review will be a scientific report or a culture-war rant. However, anyone who cares about science and the well-being of young people should at least be prepared to read the review with an open mind.

Peter Sim is a retired Canadian lawyer with a focus on gender-related human rights and medical ethics issues. Follow him on Substack.

_NicoElNino_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)