From the new RACER magazine: Robert Wickens – Why I race

A 212mph crash at Pocono Raceway in his 2018 rookie NTT IndyCar Series season left Robert Wickens with a thoracic spinal fracture, a neck (...)

A 212mph crash at Pocono Raceway in his 2018 rookie NTT IndyCar Series season left Robert Wickens with a thoracic spinal fracture, a neck fracture, tibia and fibula fractures to both legs, as well as fractures to both hands, a forearm, an elbow and four ribs. Through a long period of rehab, the Canadian was a model of determination, motivation and guts, but that’s hardly a surprise: he’d always combined abundant talent with an exceptional work ethic.

While paraplegia ensures the flesh is unavoidably weaker, the spirit is so willing that this year Wickens will compete in the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship. After three highly-successful seasons in Michelin Pilot Challenge with Hyundai, he will now get to race DXDT Racing’s Chevrolet Corvette Z06 GT3.R in IMSA’s GTD class in multiple events, starting at the Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach, April 12.

RACER: Congratulations on your latest move. How did the opportunity come about?

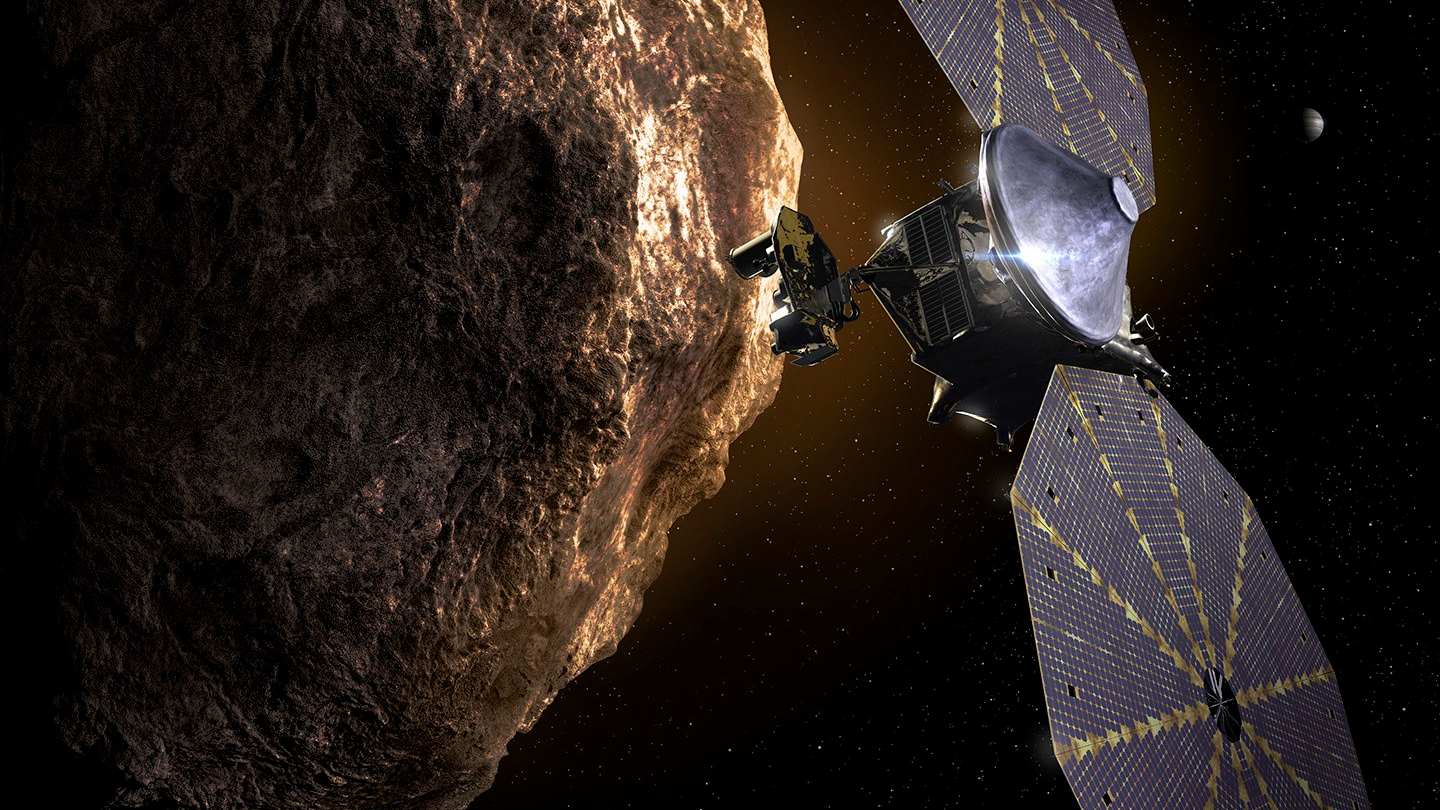

ROBERT WICKENS: I’d always been open about my ambitions to get to the WeatherTech Series, and last year David Askew from DXDT reached out and said he wanted to get into IMSA for 2025, too. Then Bosch came to the table and worked with Pratt Miller and Corvette Racing to develop a brake-by-wire hand control system that works for me and works with the Z06. We didn’t have time to prove the system’s reliability before the Rolex 24 At Daytona and the team needed to fill its endurance race lineup, so I’ll also miss the other IMSA endurance rounds. But I have the five “sprint” races on the GTD schedule, and I’m determined to make the most of a great opportunity.

It’s great to know your racing urge is as strong as ever. When did motorsports become all-consuming?

Since I was two, I was obsessively playing with toy cars, and then I saw “Days of Thunder” and my grandfather edited the video to make a version without the dialog and romantic scenes, just the racing. I had it on constant loop! When I became aware that racing was shown on TV, I’d watch Formula 1, Indy cars and NASCAR, and the whole family became fans.

When I was five, we all went down to a NASCAR race at Michigan Speedway, and there I drove a concession go-kart. Right then, I fell in love with racing.

One day, when I was about six, a kid came into school showing pictures of him racing a kart at a track 15 minutes away. That weekend, as a family, we went to check it out, and I told my parents I wanted to race go-karts. We didn’t know I was too young to race in Canada, so for the first year of us having a kart, my older brother was the one racing. My first year was 1997.

We’d bought used equipment, so we weren’t running the latest engine spec, didn’t know anything about carburetion, and probably had a different tire compound on each corner! But I started getting top fives and the odd podium. Then an engine builder gave us a basic tune-up and suddenly I started winning. And when we found out we could change gear ratios, I was even more competitive.

You’re renowned for hard work and being very detail-oriented. When did that originate?

My family sacrificed everything to help me. As I moved up categories to faster karts, we traveled to events across Canada and the U.S. and built up a lot of debt. To pay it off, my parents had to sell our house and move in with my uncle. I had to make a career out of this because my parents didn’t have anything any more, so that’s why I worked so hard.

Regarding technical details, I figured that since I didn’t bring money, it’s good to have another selling point. My pitch was kinda, “I can make your team better: if you hire me, you’ll get results that will make other good drivers willing to pay to drive for you for years to come.”

You finished top three in every junior championship you completed, you were part of the Red Bull Junior team, and you tested F1 cars. Was it hard to step off the open-wheel ladder to join the DTM series?

Yeah, it was. I’d been reserve driver for Marussia F1 team in 2011, and as a prize for winning the Formula Renault 3.5 Series, I got a test with the Lotus F1 team, so I drove both those cars in Abu Dhabi. My goal had always been to become Formula 1 World Champion. But after that Abu Dhabi test, Toto Wolff invited me to test a DTM Mercedes. I flew to Stuttgart, met with Toto, Norbert Haug and HWA Team’s CEO at the time, Gerhard Ungar, did the test, and they offered me a five-year DTM contract. That length of contract meant I was kinda giving up on my Formula 1 dream. But Ron Fellows, who’d been a mentor for my entire career, had taught me that although you should always set your goals high, at some point you’ve got to recognize the bigger goal – to be a pro, earning a living doing something you love. So for six years, I was a DTM guy.

Then, in 2017, Toto Wolff held a conference call to tell us Mercedes would leave DTM at the end of ’18. That put the future of DTM up in the air, so I didn’t want to wait until 2018 and become one of possibly 20 A-class pros hunting for rides. I’d recently done a ride-swap event with Hinch , where I tried his IndyCar at Sebring and he drove a Mercedes DTM car at Vallelunga. At Sebring, I’d had casual conversations with Sam Schmidt, Ric Peterson and Piers Phillips, so after Toto’s news, I called SPM and said, “Hey, have you got anything in IndyCar for 2018? I’m on the market.” It was a bittersweet way to end my six-year DTM journey because although I’d taken several wins, I never won a championship.

How was that switch back to open-wheel cars?

The physicality was a big adjustment. In DTM, the engineers didn’t want me above 150lbs, so the first IndyCar test I did at Sonoma was a slap across the face. I was losing two-tenths to Hinch just at Turn 1, because he could stay flat through there on new tires, where I literally couldn’t turn the wheel without backing off! I had four months to get ready, do two workouts a day, and by the start of the season at St. Pete, I’d put on 25lbs of muscle.

You took pole on your debut, and 13 races later you were sixth in points with four podiums to your name. Then came Pocono. We feared for your life, then feared for your future. And then we saw you rise. Did being habitually tough on yourself help you maximize what was possible in rehab?

There’s no prognosis for paralysis – maybe you get some muscles working properly, maybe you don’t. But my philosophy was that if I didn’t do absolutely everything I could, I’d always question, “Would I have walked again if I’d put in more hours?”

I was starting to get little muscle flickers, so when everyone said, “You need rest,” I’d reply, “I’ve seen results, I’m not stopping!” But the tempo was so high, it was barely sustainable, working out six hours a day, six days a week. I’d been 170lbs going into Pocono, and by the time I was out of my coma I was down to 116. I was a toothpick.

How did you set the bar, in terms of “If I can achieve X, I’ll race again”? Or was it an ever-shifting bar?

It shifted. The first 18 months after the accident, I didn’t think hard about racing; I just wanted to ensure I had the best possible quality of life. Having my fiancee Karli by my side, I wanted to get strong for the wedding, and get through our first dance. I had to bulk up, and get back any nerve fiber response I could. But during the COVID pandemic, the gyms shut down so I couldn’t do rehab, and after two weeks I felt great, because I’d let my muscles recover; that’s what the physios had meant about resting.

During the pandemic, esports took center stage, and I got a sim at home and raced IndyCars in the virtual world. From that first virtual race, I was like, “OK, how do I go racing again?” Then, in 2021, Bryan Herta called and offered me a test at Mid-Ohio in his team’s Hyundai Veloster N. It was raced in the Michelin Pilot Challenge by Michael Johnson, who uses hand controls. I’ll forever be grateful to Bryan for that opportunity. It felt fantastic to be on track again after almost 1,000 days.

And when Bryan and Hyundai signed you to race in MPC in 2022, how difficult was it to make the Elantra work for both yourself and a co-driver?

I’ve been very fortunate that my co-driver in ’22, Mark Wilkins, and my co-driver in ’23 and ’24, Harry Gottsacker, understood that because I don’t have abdominals and stabilizing muscles, I need a race seat that fits me extremely well. They were very accommodating, letting me choose what I need, then they made small changes to work for them, too. From the hand-control side, it was only me who used them. I had a fly-by-wire throttle operated by paddles that Mark and Harry disengaged when I handed over the car, and a ring behind the steering wheel that I’d pull to actuate the brake pedal, and they could just ignore.

Then Bosch approached me in 2023 and said they had a brake-by-wire system they felt would work for me. We had it installed for the last two races of 2024, and have now evolved it further to put into the Corvette for this year. It took a lot of time and effort so I’m grateful to Bosch, Pratt Miller, Corvette Racing and DXDT. Now, David Askew and I have together taken a leap of faith. They scheduled a two-day test after the Twelve Hours of Sebring, and then I’m going to be racing in Long Beach.

What expectations have you set yourself?

I’m not the driver I was in 2018. The way I could use the pedals to manipulate a car’s behavior in braking and cornering is something I’m still learning to replicate to the highest standard with hand controls, to maximize the car’s potential. The ceiling for Bosch’s braking system is so much higher than the mechanical system, but I’ve had to learn its feel, and I’ll also be learning a completely different car. It’s a case of implementing knowledge and experience, but in a different set of circumstances, and it’s going to be a lot of hard work. But it’s going to be exciting and interesting – and fun.

Reset. Restart. Those are the underlying themes of the latest issue of RACER magazine, The New Challenges Issue. We’ve always celebrated the spectacle – the color, the speed and the drama – showcased the stars and cars, and told the stories that take you inside the sport, but now we’re delivering it in a bigger, better and more vibrant way. With its stunning photography, leading-edge design and engaging writing, RACER’s been leading the field since 1992, and now we’re elevating the magazine experience once again.

CLICK HERE to purchase the new issue of RACER. And to have the new-look RACER magazine delivered to your mailbox six times per year, CLICK HERE to check out print and digital subscription options.