Every Small Action Magnifies

Decades ago when I was hoping to become a scientist, I got a master’s degree dealing with the actions of water in the desert, part of which was studying the hydrology of flash floods on unvegetated bedrock. One term for the result is a “slot canyon.” When people died in a flash flood in a […]

Decades ago when I was hoping to become a scientist, I got a master’s degree dealing with the actions of water in the desert, part of which was studying the hydrology of flash floods on unvegetated bedrock. One term for the result is a “slot canyon.”

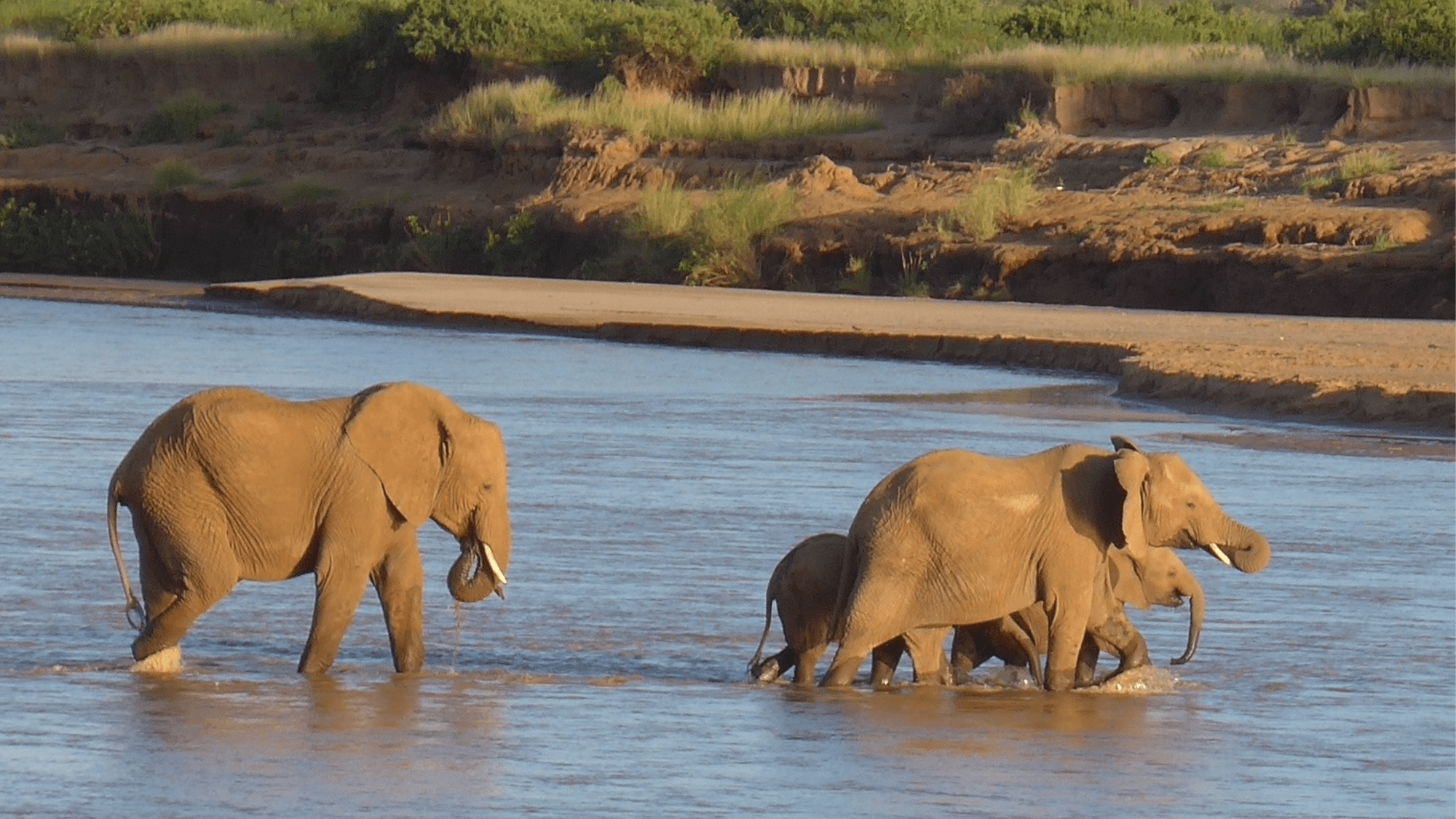

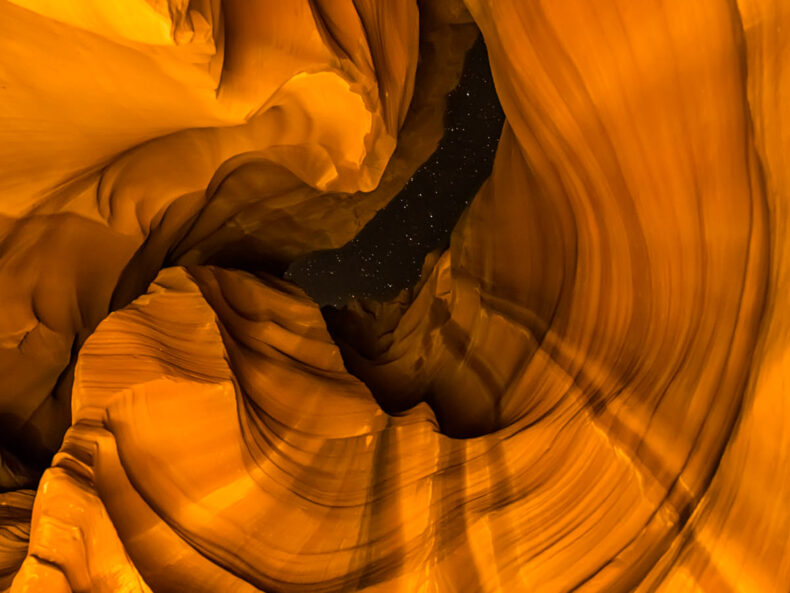

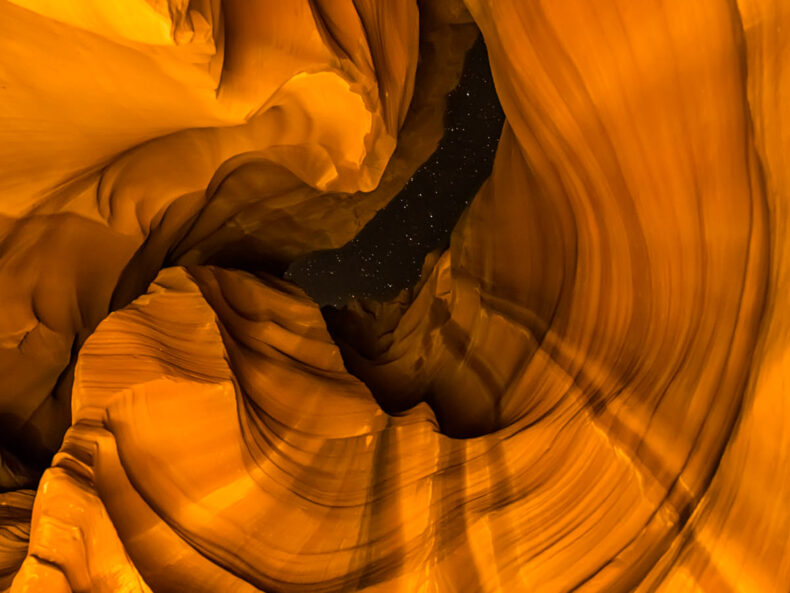

When people died in a flash flood in a narrow canyon in Zion years back, NPR brought me on to explain what happened and why. I told listeners that these desert rainstorms touch ground far away and run fast over forty or fifty miles, finding people in a dry, sunlit cathedral dazzled by the convoluted walls around them, perhaps wondering what could have formed such a place. Water and debris arrive in what is called a “flood bore,” either a towering wave or a long, inescapable slope: ankles, knees, and once it’s to your waist you’re ass over teakettle. It keeps rising ten to forty feet or more, a maelstrom of mud, water, and boulders leaving a log jammed between walls sixty feet up in the air. No skill or strength can save you. Everything is up to the flood.

I interviewed workers on body recoveries, usually Park Service or land agency employees telling me of a wedding ring being the only thing still on a man, or how three people were all swept together under a ledge miles from where they started as if the water took them in its hand. I was told about a person’s face like a mask, only the face, no bone or anything else. The flood seems to have some kind of agency. Anything in the way enters into the equation.

The shapes of these canyons are formed by floods wearing against rock over eons, what seems like pure madness and violence leaving behind an elegant array of fans and flutes, galleries of hydraulic bedforms. It’s the same sort of thing you see when rivulets of rainwater come down your windshield not taking straight paths but snaking all over the place. This is a fluid shedding energy as it flows. With these ropes twisting through the insides of floods, bouncing off the same obstacles of boulders or hollows in the rock, a map is left behind. That is what you are walking through, a visual representation of hydraulic chaos and the order that arises, and it can go on for miles.

When I walk down the bottom of these canyons, climbing over choked boulders, I know why people get caught. These are such unique geographic features a curious human eye really ought to make contact. The way rock surfaces treat light is like an artist’s brush and at night they carve a slender ribbon of stars. After Aron Ralston famously cut off his arm to escape one of these canyons in Utah, he and I returned to the site and sat on the boulder that had rolled and trapped him for nearly five and a half days. A Hollywood movie was made about his misadventure and I was there as a consultant to the film. Where the boulder kissed the sandstone wall were nicks from his pocket knife, evidence of thinking he could carve enough away to get the boulder to roll and free his crushed arm, which didn’t work. As we sat on the boulder in eerie mid-day half-light, Ralston told me that on the fourth day he was still taking scenic pictures. He said it was an unimaginable experience being forced not to move as light grew each dawn, seeming to come out of the rock, followed by a long day of shadow play before falling into prismatic dusk. Regardless of the pain and fear, he said it was the most beautiful thing he’d ever witnessed.

Traveling from one slot canyon to the next, sometimes using ropes to get in or out of them, I became a student of chaos. More accurately, I became a student of self-organization: the process by which a system structures itself, learning and adapting. It is the spontaneous emergence of order that happens wherever chaos touches. Every knickpoint and swirl starts a process that magnifies into echoes that are polished out of the rock.

We are like this, too. In the chaos of the flood, we bend and reshape. We resist and our resistance becomes the form around us. Every small action matters and magnifies. To be in the heart of it is tumultuous, out of control. I spoke with a sole survivor who had been tumbled inside a washing machine of boulders when a current whipped him upward and he shot into the air like a cannonball. He said for a moment he could see everything: the walls around him, the churning mud and destruction below. There was nothing he could do and he plummeted right back in. Happenstance spit him into a shallow, calm eddy where he crawled out. The other two with him, his sister and brother in law, did not make it.

Floods from that storm belched into the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, darkening the river with mud and debris. This was a long time ago, summer of 1997, and I was doing my fieldwork not far downstream, camped along the river alone. Rafts came by and someone shouted there’d been a flood, which I’d seen, perched on a high, safe ledge when it hit, watching a dragon of water and debris rip through my own canyon. I’d set up markers and timed and measured the rise and duration, and there would later be data, estimates of sediment load and liquid volume, the path of the storm born from moisture off the Pacific 500 miles away, which started with butterfly wings on the other side of the planet.

The person on the raft shouted to watch for bodies, which I never did see. River runners would find them and tie them to shore so Park Service rescuers could later lift them out by helicopter. As the rafts floated downstream, I sat alone not sure how to balance terror and beauty, but I saw how seamlessly they fit together. The canyon I was in was named “Tuckup.” The canyon they had been in was on the map as “Haunted.”

That morning I had swum through still, muddy waters left by the flood from the day before. The surface was as red as jasper and my every stroke sent out a small wake that lapped and echoed against the walls.

Photo by Chris Eaton: https://www.chriseatonphotography.com/