Douthat on the best argument against God (too much evil), but he argues that God is evidenced also by too much GOOD

Four days ago I presented NYT columnist Ross Douthat’s favorite argument for God’s existence. (Douthat is a pious Catholic.) That argument turned out to be pretty lame: it was the claim that “the universe was intelligible and we can use reason to understand it.” On top of that sundae, he placed the cherry of “also, … Continue reading Douthat on the best argument against God (too much evil), but he argues that God is evidenced also by too much GOOD

Four days ago I presented NYT columnist Ross Douthat’s favorite argument for God’s existence. (Douthat is a pious Catholic.) That argument turned out to be pretty lame: it was the claim that “the universe was intelligible and we can use reason to understand it.” On top of that sundae, he placed the cherry of “also, humans can go far beyond this: they can do stuff like playing chess or the piano—things we couldn’t possibly have evolved to do.” (I am giving my characterizations here, not his quotes.)

If you have two neurons to rub together, and know something about evolution, you can easily see why this argument is not convincing evidence for a deity, much less the Catholic deity. Nor is it evidence for the existence of an afterlife, a crucial claim that bears on Douthat’s latest column, one that lays out what he sees as the best argument against the existence of God. That argument is what I’ve called the “Achilles heel of theism”: the existence of physical evil that inflicts suffering and/or death on undeserving (“innocent”) people.

The previous column was an excerpt from his new book, Believe, Why Everyone Should Be Religious, and I’m sure the “evil” issue is also an important one in his book. But this column doesn’t say it’s an excerpt, so it’s not self-plagiarism. Nevertheless, I find Douthat’s reasoning still pretty weak, for he gives five lame arguments why we should dismiss the existence of evil as a telling argument against God.

Douthat is turning into the C. S. Lewis for Generation X, someone who proffers superficially appealing but intellectually weak arguments simply to buttress the longings of those who want there to be a God. I think the NYT itself is catering to this slice of society, for it’s increasingly touting religion to its readers. Do you agree? And if you do, why would the NYT be doing this?

You can read Douthat’s arguments by clicking on the screenshot below, or you can find the full article archived here:

Douthat begins by again dismissing naturalism as strong evidence against a god:

The most prominent argument that tries to actually establish God’s nonexistence is the case for naturalism, the argument that our world is fundamentally reducible to its material components and untouched in its origins by any kind of conscious intention or design. But unfortunately, no version of the case for naturalism or reductionism is especially strong.

Well, I’d say that two things do strengthen “the case for naturalism.” The first is that the laws of physics appear to apply everywhere in the universe, and quantum mechanics predicts what we see to an extraordinary degree of accuracy. There is no “god parameter” in these laws; they are perfectly naturalistic. (I suppose Douthat would respond that our ability to discern the laws of physics is itself evidence for God.)

Second, even in our own everyday life, the known laws of physics seem to account for everything without anything major missing. I won’t go into this; just read Sean Carroll’s two pieces, “The Laws Underlying The Physics of Everyday Life Are Completely Understood” and “Seriously, The Laws Underlying The Physics of Everyday Life Really Are Completely Understood.” Carroll is not maintaining that we understand everything about physics (e.g., black energy); his thesis is this:

Obviously there are plenty of things we don’t understand. We don’t know how to quantize gravity, or what the dark matter is, or what breaks electroweak symmetry. But we don’t need to know any of those things to account for the world that is immediately apparent to us. We certainly don’t have anything close to a complete understanding of how the basic laws actually play out in the real world — we don’t understand high-temperature superconductivity, or for that matter human consciousness, or a cure for cancer, or predicting the weather, or how best to regulate our financial system. But these are manifestations of the underlying laws, not signs that our understanding of the laws are incomplete. Nobody thinks we’re going to have to invent new elementary particles or forces in order to understand high-Tc superconductivity, much less predicting the weather.

But I digress, but so did Douthat, who says that “the anti-reductionist argument” (against god) “clearly wins out.” Perhaps in his mind it does, but he’s hardly unbiased!

Douthat then specifies the argument from evil that he finds the most telling argument against God, but for the rest of the article he manages to argue that it’s not very telling:

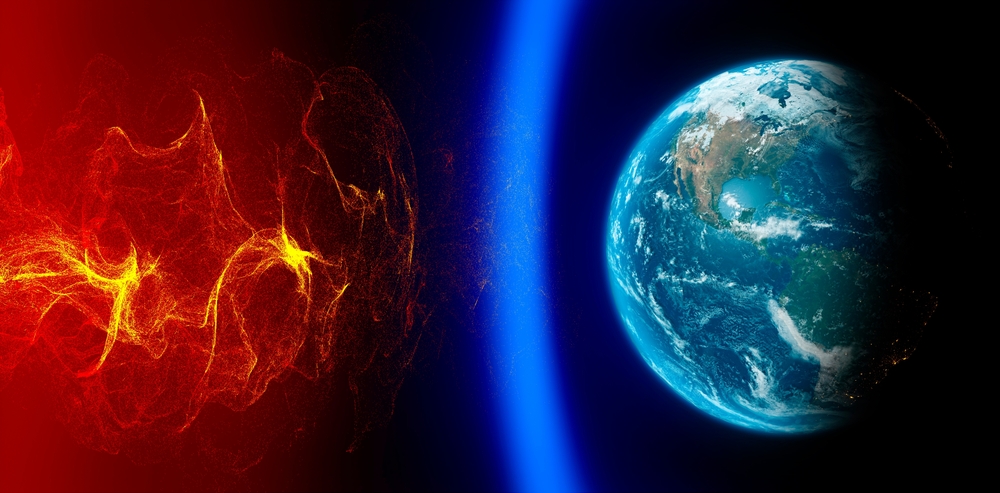

So instead of talking about an argument for disbelief that I struggle to take seriously, I’m going to talk about an argument that clearly persuades a lot of people not to have religious faith and does have a form of empirical evidence on its side. That’s the argument from evil, the case that there simply can’t be a creator — or at least not a beneficent one — because the world is too laden with suffering and woe.

He then, like C. S. Lewis, hastens to reprise what he just said: that this is an argument against a particular kind of god, one that is beneficent or omnbeneficent. And that god, of course, is the Abrahamic God, including Douthat’s. So if God is kindly and all-good, why does he let little children die of leukemia, or get other diseases that cause immense suffering, not to mention the same suffering in innocent adults (or are they all sinners?). And why do tsunamis, volcanoes, and earthquakes kill millions of people, many of whom don’t deserve to die regardless of your criteria for whether someone is a “good person”.

Douthat responds with some answers that I’ve put under headings I invented. His responses rest largely on his claim that we don’t know that there is too much suffering.

We don’t know that there’s too much suffering!

The other interesting point about this argument is that while its core evidence is empirical, in the sense that terrible forms of suffering obviously exist and can be extensively enumerated, its power fundamentally rests on an intuition about just how much suffering is too much. By this I mean that many people who emphasize the problem of evil would concede that a good God might allow some form of pain and suffering within a material creation for various good reasons. Their claim, typically, is that our world experiences not just suffering but a surfeit of suffering, in forms that are so cruel and unusual (whether the example is on the scale of the Holocaust or just the torture of a single child) as to exceed anything that an omnipotent benevolence could allow.’

Indeed, various apologists have countered the Argument from Suffering by saying that suffering is an inevitable concomitant of the kind of world that God would want to create, presumably the best of all possible worlds. (Unless, that is, he’s created the world as a theater for his own amusement.) Suffering, they say, is an inevitable byproduct of free will, which we must have because to get to Heaven we must freely choose Jesus as our savior. Putting determinism aside (while accepting its truth), this is not a satisfactory answer. God knows already (as do the laws of physics) whether we’ll choose Jesus, and he could make us all choose Jesus while still thinking that it really was a free choice. (It’s not free if God knows it in advance!) Besides, how does a kid with a terrible, fatal disease result from free will? Free will for cancer cells? And what about other non-moral “physical evils” like earthquakes?

Well, theologians have worked that one out, too. To have a viable planet, they say, we have to have tectonic plates, whose shifting results in earthquakes and other sources of mortality. But if God was omnipotent, he could have created such a world! Here we see another dumb argument, but theologians are paid to make such arguments, not to find the truth.

Finally, I see “too much suffering” as is “any more suffering than is required by God’s plan”. But how do we judge that? Even if everything is made right on Judgment Day, with the kids who die young automatically going to Heaven (this is another inane theological response), there was more suffering than necessarily to achieve that end. Kids could die painlessly! I say that any suffering at all that cannot be explained by human reason is too much suffering, and if Douthat responds, “well, we don’t know God’s plan,” I would say, “Well, you don’t seem to know much about God. How do you know that he’s benevolent and that there’s a Heaven?” And here I must stop to recount a passage from Hitchens’s book attacking Mother Theresa: The Missionary Position:

Mother Teresa (who herself, it should be noted, has checked into some of the finest and costliest clinics and hospitals in the West during her bouts with heart trouble and old age) once gave this game away in a filmed interview. She described a person who was in the last agonies of cancer and suffering unbearable pain. With a smile, Mother Teresa told the camera what she told this terminal patient: “You are suffering like Christ on the cross. So Jesus must be kissing you.” Unconscious of the account to which this irony might be charged, she then told of the sufferer’s reply: “Then please tell him to stop kissing me.”

At any rate, it’s in this section of this article that Douthat reveals his confirmation bias. He’s making counterargument only to knock them down, because, of course, he has to believe. (I’d love to ask him, “Ross, since you can rationalize evil this way, is there anything that would make you reject belief in God?” Look at this:

Of course, as a Christian, I don’t think [the Argument from Evil is] a good reason to choose against my own tradition, which brings me to the second challenge. . .

Of course! He will never find a good reason to choose against his own “tradition.” (Note: In Faith Versus Fact I at least lay out a scenario that would make me tentatively accept the existence of Jesus and the Christian God.) This brings us to Douthat’s second reason to downplay the force of the Argument from Evil:

The Bible shows a lot of evidence for undeserved evil. This is a “this-I-know-because-the-Bible-tells-me-so” argument, and it’s dumb, because it doesn’t touch the problem. It only says that God was not omnibenevolent in the Bible.

To the extent that you find the problem of evil persuasive as a critique of a God who might, nevertheless, still exist, you would do well to notice that important parts of that critique are already contained within the Abrahamic tradition. Some of the strongest complaints against the apparent injustices of the world are found not in any atheistic tract, but in the Hebrew Bible. From Abraham to Job to the Book of Ecclesiastes — and thence, in the New Testament, to Jesus (God himself, to Christians) dying on the cross — the question of why God permits so much suffering is integral to Jewish and Christian Scripture, to the point where it appears that if the Judeo-Christian God exists, he expects his followers to wrestle with the question. Which means that you don’t need to leave all your intuitive reactions to the harrowing aspects of existence at the doorway of religious faith; there is plenty of room for complaint and doubt and argument inside.

This is the kind of palaver that C. S. Lewis shoveled down the gaping maws of British Christians, as if they were baby birds begging for a meal. Because there is contradictory evidence for an omnibenevolent God in the Bible (cf., the story of Job), God wants us to ponder the question and raise doubts. The problem with this is that the Bible doesn’t give us any answers to the question of evil.

We shouldn’t rely on our intuitions about whether there’s “too much evil” to count against God’s existence. This is simply the first argument above, repeated:

Then the third challenge: Having entered into that argument, to what extent should you treat your personal intuitions about the scale of suffering as dispositive? I don’t just mean the intuition that something in the world is out of joint and in need of healing. I mean the certainty that those wounds simply cannot be healed in any way that would ever justify the whole experience, or the Ivan Karamazov perspective that one should refuse any eternal reconciliation that allows for so much pain. Those are powerful stances, but should a mortal, timebound, finite creature really be so certain that we can know right now what earthly suffering looks like in the light of eternity? And if not, shouldn’t that dose of humility put some limit on how completely we rule out God’s perfect goodness?

This is the “suffering will be compensated in ways we can’t understand” argument. But if Douthat believes in God because experience tells him it’s right to believe, how can his experience allow him to dismiss arguments against his benevolent God? This is just a “God works in mysterious ways” argument, but I could note that it’s more reasonable to assume that God is playing with people for his own amusement, and doesn’t really care whether good always prevails. But wait! There’s more!

Suffering is overrated. Things aren’t as bad as they seem because privileged atheists exaggerate how bad suffering is.

This again is a repeat of previous arguments with a twist thrown in. I can’t believe Douthat really makes this argument, but he does:

From what perspective are you offering this critique of God? If you are in the depths of pain and suffering, staring some great evil in the face, adopting atheism as a protest against an ongoing misery, then the appropriate response from the religious person is to help you bear the burden and not to offer a lecture on the ultimate goodness of God. (Indeed, in the Book of Job, the characters who offer such a lecture stand explicitly condemned.)

But given that atheism has increased with human wealth and power and prosperity, we can say that some people who adopt this stance are doing so from a perspective of historically unusual comfort, in a society that fears pain and death as special evils in part because it has contrived to hide them carefully away. And such a society, precisely because of its comforts and its death-denial, might be uniquely prone to overrating the unbearability of certain forms of suffering, and thereby underrating the possibility that a good God could permit them.

I’m dumbfounded. Is this even an argument? I’ll leave smarter readers to deal with it, and pass on to Douthat’s fifth way of dismissing the Argument from Evil:

There’s a lot of good in the world as well, perhaps too much good! So we need God to explain why things are so good.

This is a defense I haven’t heard before, probably because it’s so weird and lame. Let’s look at it first:

Then the last challenge: If the intuition against a benevolent God rests on the sense that we are surfeited with suffering, the skeptic has to concede that we are surfeited in other ways as well. Is it possible to imagine a world with less pain than ours? Yes, but it’s also very easy to imagine a world that lacks anything like what we know as pleasure — a world where human beings have the same basic impulses but experience them merely as compulsions, a world in which we are driven to eat or drink or have sexual intercourse, to hunt and forage and build shelter, without ever experiencing the kind of basic (but really extraordinary) delights that attend a good meal or a good movie, let alone the higher forms of eros, rapture, ecstasy.

Indeed, it is precisely these heights of human experience that can make the depths feel so exceptionally desolating. This does not prove that you can’t have one without the other, that there is a necessary relationship between the extremes of conscious experience.

But it makes the problem of good — real good, deep good, the Good, not just fleeting spasms and sensations — at least as notable a difficulty for the believer in a totally indifferent universe as the problem of evil is supposed to be for the religious believer.

Well, we’re evolved to seek out those things that increase our survival and reproduction, and that seeking is facilitated by neurologically connecting these fitness-conferring features with pleasurable or appealing feelings. We love sweets and fats because for most of our evolutionary history they were good for us, so natural selection worked on our taste buds and brain to make their consumption pleasurable. Orgasms almost certainly evolved as a form of extreme pleasure that drives us to reproduce: those who get the most pleasure leave the most genes. Further, for most of our evolutionary history we lived in small, close-knit groups in which members knew each other. That would lead to the evolution of reciprocity: doing good and helping others because it keeps the group together (with you retaining your fitness) and leading to various forms of “moral” thinking and behavior. As for “eros, rapture, and ecstasy,” why can’t they be byproducts of seeking the kind of enjoyment associated with higher fitness? I will grant here that I don’t understand how the widespread making of and appeal of music occurred, but does that give evidence for God? Do music and art simply constitute too much good stuff to appear in a secular world?

In the end, I see naturalism (including evolution) as able to explain good and especially physical evil, while Douthat’s idea of God can explain good by assumption, but has to be stretched further than Gumby to explain physical evil.

But again I would level this challenge at Douthat, whom I see as deluded: What observations or occurrences would convince you that your belief in the Christian God, and in your Catholicism, is wrong? If kids dying in intractable pain won’t do it, I don’t think anything will.

Further, Mr. Douthat, what evidence would convince you that there is an afterlife: a Heaven, a Hell, or both? Even if you accept Douthat’s specious evidence for the existence of a divine being, I have no idea why, aside from the Bible and propagandizing by believers, he accepts the existence of an afterlife. Yet its existence would seem to be crucial for justifying how evil can exist in God’s world.

Here’s a guy far smarter and more eloquent than I making the argument from evil on Irish television. Stephen Fry got into trouble for saying this, and almost was charged with blasphemy or hate speech.