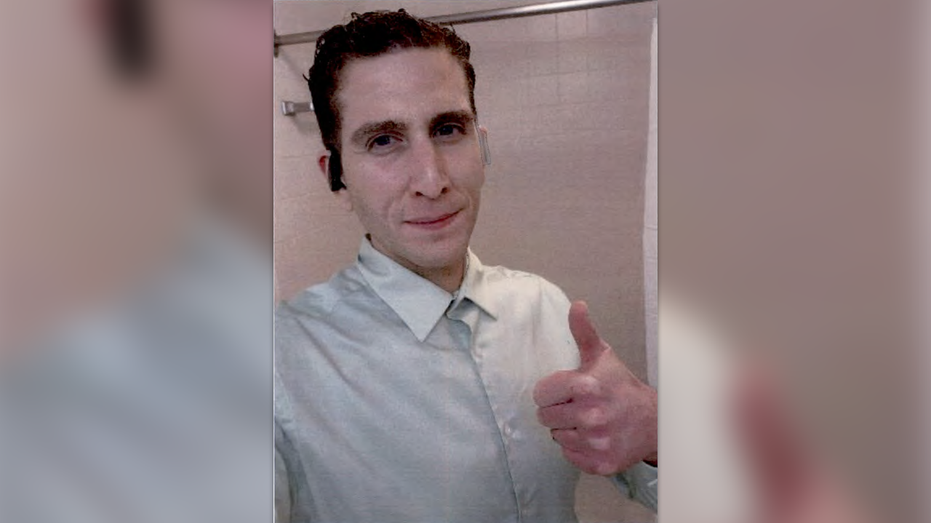

A Conversation With Jeffrey Goldberg About His Extraordinary Scoop

How The Atlantic’s editor in chief found himself in a group chat with Trump-administration officials who were planning an attack on Yemen

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

The Trump administration has provided many jaw-dropping moments, but few have been as shocking as editor in chief Jeffrey Goldberg’s scoop published today. Goldberg reported on how he was inadvertently added to a discussion of a military strike on Houthi militias in Yemen, conducted over the encrypted messaging app Signal. In essence, a reporter was invited to listen while the nation’s top security officials weighed and debated a military action, and was sent detailed information about the strike.

Even President Donald Trump seemed unaware of the breach. “You’re saying that they had what?” he replied when asked about the news. Trump added that he is “not a big fan of The Atlantic,” something he’s previously made clear, and which makes the unintentional leak all the more remarkable. A spokesperson for the National Security Council said, “This appears to be an authentic message chain, and we are reviewing how an inadvertent number was added to the chain.”

I called Goldberg this afternoon to learn more about how the story came about and what the disclosure reveals about the Trump administration. This interview has been condensed and edited.

David A. Graham: Has anything like this ever happened to you before?

Jeffrey Goldberg: I think that on one level, this is very relatable. Everyone has sent a text or an email to an unintended recipient, and sometimes they’ve embarrassed themselves by doing that. This is, I would say, at a different level—but it kind of proves a point, which is that there’s a reason people who work on sensitive issues in the government aren’t supposed to use Signal, even though it is end-to-end encrypted. Anyone can use Signal, so if you’re not careful, you might pull into your conversation a Houthi sympathizer or a magazine editor.

Our colleague Shane Harris points out that the phones of top senior defense and national-security and intelligence officials are targets of intelligence operations. Imagine what you can do if you saw everything that the CIA director may be texting, even on a secure phone—especially on a secure phone. I’m mindful of the fact that the Trump team has already dealt with a serious issue in the securing of sensitive documents in Mar-a-Lago. If you’re going to make a big deal about Hillary Clinton’s emails, you may want to have excellent communication hygiene.

David: Tell me how you came to conclude that this group was real.

Jeffrey: It was actually chilling: 11:44 a.m., Saturday the 15th, Eastern Time, in my car in a parking lot, just checking my phone, and I see a text from Pete Hegseth, or somebody who’s hoaxing me as Pete Hegseth. It provides information about upcoming military operations with timings attached: This is going to happen. Then this happens, then this happens, and this happens. I’m sitting there in my car and thinking I’m about to find out if this was an elaborate scam or not. So I thought to myself, I’m sitting here for the next two hours with my hands around my phone. I check on X around 1:55, and yes, Sanaa is being bombed, so then I have the realization that this is almost certainly a real channel and not just an elaborate fakery of some sort. And that’s when I began to realize that I had to write about this massive security breach.

David: You have done a lot of sensitive national-security reporting. Have you ever received any information like this?

Jeffrey: No, nothing like this. This was like an intravenous drip of information that no one in the government thinks journalists should have. Until almost the very last minute, I could not believe that this was actually happening, that there could be a Mack-truck-size breach, that somehow, the editor in chief of The Atlantic was invited into a conversation with the intelligence agencies, secretaries, the national security adviser. Like most reporters, I’ve been a recipient of leaks. A leak is a totally different thing. That’s a whistleblower trying to make complaints. This is just reckless.

David: There’s the horror that something like this would happen on an operational level, but in terms of what we learn from the substance of the conversation, what are the most important things that people should take away?

Jeffrey: The actual conversation that they have is fascinating, and in a certain way impressive. It’s nice to see that they’re disagreeing with one another. It’s very useful for the public to know that the vice president has a more hands-off approach than other members of the administration. One of the things that I found interesting was that when a person named “S M” in the chat, who I took to be Stephen Miller, comes in and says, “As I heard it, the president was clear,” this kind of shuts down the conversation. It suggests that Stephen Miller can be in a conversation with, among others, the vice president of the United States and still can get his way. (Miller did not reply to a request for comment or confirm that he is “S M.”)

David: In addition to the question of how secure Signal is, this is also notable, because without this report, none of these conversations might be preserved for posterity. You note that National Security Adviser Michael Waltz set some messages to disappear after a week or so.

Jeffrey: This is an interesting question: Are they using Signal because it’s convenient? Are they using Signal because it disappears? According to the experts Shane interviewed, the administration should not have established a Signal thread for such conversations in the first place, but once it did, what one is supposed to do legally is copy an official government account, and that government account will then send these threads to the National Archives for posterity, for research, for accountability. But if you’re using a disappearing-text app, I don’t know. That’s one of the questions that I’ve asked and have not gotten answered yet.

David: It is remarkable that this would happen with any reporter. It’s even more remarkable that this would happen with someone like you, and with a publication that has been specifically singled out by the president. Do you have any sense of how this happened?

Jeffrey: I literally have no idea. The remarkable thing is that no one in the group asked, Who’s JG?, and when I removed myself from the group, seemingly nobody said, Hey, why did JG leave?

David: Are you concerned about retaliation from the Trump administration because of this story?

Jeffrey: It’s not my role to care about the possibility of threats or retaliation. We just have to come to work and do our jobs to the best of our ability. Unfortunately, in our society today—we see this across corporate journalism and law firms and other industries—there’s too much preemptive obeying for my taste. All we can do is just go do our jobs.

-(1).png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)