3 warning signs about the future of government oversight

Taken together, these three elements will show the American public whether the Trump administration is serious about federal oversight.

President Trump’s purge of 18 inspectors general removed the independent watchdogs for virtually all of Cabinet agencies, including myself and several longtime stalwarts in the oversight community.

The purported justification (as stated in the White House emails that fired us) was due to Trump’s “changing priorities.” But many have argued that it reflects something far more sinister: a desire to decapitate Offices of Inspector General and leave them so weakened that they cannot conduct meaningful oversight.

Here are three warning signs that will tell you whether we were the proverbial canaries in the coal mine.

The first sign is how the White House handles the now-vacant seats with acting inspectors general. Current law provides that, if the inspector general position becomes vacant, the first assistant assumes the role of acting inspector general. These first assistants are usually the deputy inspectors general, who by and large are tremendous public servants dedicated to rooting out waste, fraud and abuse inside their agencies.

But in his first administration, Trump named political appointees in those acting roles. That meant they were wearing two hats — one executing the administration’s policies and the other overseeing those very programs.

That so-called “dual-hatting,” however, presents inextricable and unresolvable conflicts of interest. How can an official be viewed as fairly and independently assessing an agency’s programs when they are beholden to the political leadership for their job, not to mention their salary and bonus?

Unlike an inspector general, whose salary is set by statute and who cannot receive a bonus, such dual-hatted officials would inevitably have an incentive to call balls and strikes in favor of their boss. In fact, the prospect is so untenable that Congress prohibited such acting inspector general appointments in 2022, specifically due to these conflicts of interest.

But considering that the White House ignored statutory requirements in the 18 firings a few weeks ago, it is not a stretch to consider that it would ignore other statutory requirements in naming acting inspectors general now.

So why would naming political appointees as dual-hatted acting inspectors general be a warning sign? In short, these administration operatives would have the proverbial keys to the kingdom.

Namely, they would have control over ongoing investigations, meaning they could eliminate legitimate investigations into their administration peers and colleagues. They could access highly sensitive and confidential whistleblower information, including on individuals who might have lodged complaints against them, and they could water down or eliminate negative findings from audits and evaluations concerning their own programs.

Moreover, even if these appointees operated in good faith and engaged in none of these improprieties, oversight reports issued under their signature will be of limited value, written off as the findings of a political operative beholden to the administration. As such, they will inevitably lack the necessary credibility to effect positive change.

Therefore, here’s the warning sign: If — despite this litany of inexorable problems — the White House appoints dual-hatted administration officials as acting inspectors general, it would be a clear sign that the administration is not interested in meaningful oversight in the federal government.

The second warning sign is a quintessentially inside-baseball issue, but it is worth discussing, as it could be a harbinger about the future of government oversight.

Under the Inspector General Act, inspectors general are under the “general supervision” of the agency head; that term has long been interpreted by courts and prior presidential administrations to mean “nominal.” The act also states expressly that the agency head cannot “prevent or prohibit the inspector general from initiating, carrying out or completing any audit or investigation, or from issuing any subpoena during the course of any audit or investigation.”

Taken together, these statutory provisions establish that inspectors general are part of their respective agencies and report to the heads of those agencies, on the one hand, but simultaneously establish that supervision runs afoul of the Inspector General Act when it implicates their independence and ability to do their jobs, on the other.

So, for example, if an agency adopts broad security rules to enter its buildings or minimum standards for IT systems under the agency’s technology umbrella, the inspector general offices will generally be subject to those restrictions. Those sorts of mandates are broad, routine and administrative and don’t impinge on their ability to do their jobs.

However, agency heads may not tell their inspectors general to stop investigating a political official or change the scope or findings of an audit into a politically sensitive program. Those cut to the core of a watchdog’s independence and are therefore non-starters under the Inspector General Act.

The warning sign here is if executive branch officials adopt an unprecedentedly broad interpretation of “general supervision” and expand the definition beyond anything we have seen in the 45-year history of inspectors general. Will the head of an agency, despite clear provisions to the contrary, attempt to exercise their supervisory authority to control their inspector general’s findings and recommendations? Again, this would be a tell-tale sign that the administration is not interested in independent oversight.

The final warning sign is who the president nominates to the vacant positions on a permanent basis.

Inspectors general were created to be fair, objective and independent evaluators of agency programs. The essence of that independence is that they are not beholden to a political actor, party or ideology. In short, they cannot have a stake in the outcome of their own oversight.

So, the key warning sign here is if the White House submits inspector general nominations who have backgrounds that would cause a reasonable person to question their credibility. Basically, do the nominees have extensive partisan political experience, large political donations, leadership in ideological or partisan groups or statements in speeches or social media posts that would make the American public think that they are not straight-shooters?

This does not mean individuals with such backgrounds cannot possibly be good inspectors general but it should raise red flags in Congress and with the American people about their willingness to conduct fair, objective, independent oversight.

The key question for all inspector general nominees is this: Do they have anything in their background that would suggest they would put their thumb on the scale to favor one political party or the other?

Taken together, these three elements will show the American public whether the Trump administration is serious about federal oversight.

Time will tell, but if the White House appoints dual-hatted politicos as acting inspectors general, asserts an unprecedentedly expansive interpretation of “general supervision” of inspectors general or nominates political lackeys to the open positions, we will know that the fired inspectors general were just canaries in the coalmine.

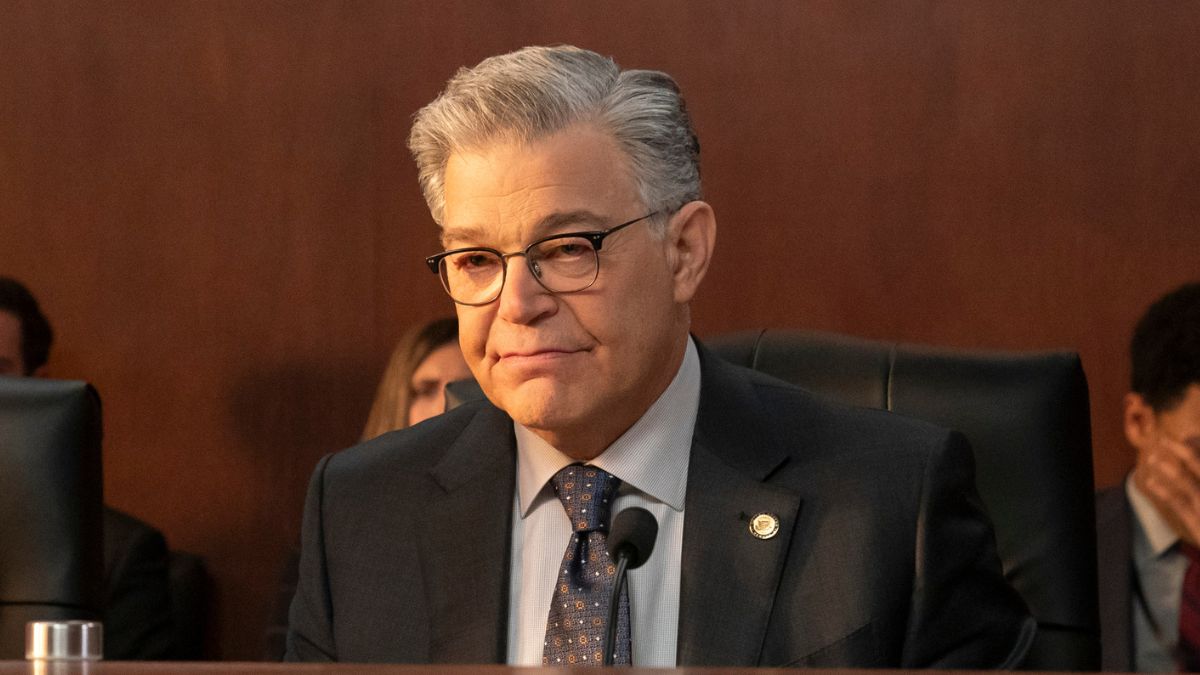

Mark Greenblatt was inspector general of the United States Department of Interior from August 2019 until January 2025. He also served as chair of the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency from 2023 to 2024 and as vice chair from 2022 to 2023.