Why the Department of Education has withstood so many assaults from the right

Many conservatives want to use the department to advance “anti-woke” policies and understand that harnessing its power can advance their objectives more than abolishing it.

President Trump insists that the Department of Education has been infiltrated by “radicals, zealots, and Marxists” and has promised to abolish it and “return” responsibility for education to the states. Both the 2024 Republican Party platform and Project 2025, which labeled it a “one-stop shop for the woke education cartel,” also demand the department’s closure. Bills have been filed in both the House and Senate to transfer the department’s responsibilities to other government agencies.

Eliminating a Cabinet agency requires legislation, of course, and Republicans lack the votes to overcome a Democratic filibuster. Even if Republicans prevail, little would change unless Congress also voted to cut education spending and repeal the plethora of laws and regulations associated with the department.

The Department of Education’s critics want to limit the federal government’s role in education, which has expanded over the last 60 years to fulfill America’s commitment to provide equal opportunity to all citizens and to meet the needs of a modern economy. At the same time, many conservatives want to use the department to advance “anti-woke” policies and understand that harnessing its power can advance their objectives more than abolishing it.

The founders viewed an educated citizenry as the best protection for democracy, but they did not believe the federal government should provide that education. Education is not among the enumerated powers granted to the federal government by the Constitution; it largely falls under the 10th Amendment, which reserves to the states or to the people powers not otherwise delegated.

During the country’s early history, most Americans received little or no formal schooling, learning instead from family, work and church. Congress “intervened in education only in ways directly related to an explicit constitutional provision,” for example, by establishing schools on American Indian reservations.

By the 1840s, universal state-funded education started to take hold in the North under the auspices of the common school movement. After the Civil War, Rep. James Garfield (R-Ohio), concerned about widespread illiteracy, especially among former slaves, urged creation of a federal Department of Education. President Andrew Johnson, assured that the new department would be largely an “empty gesture,” acquiesced in 1867.

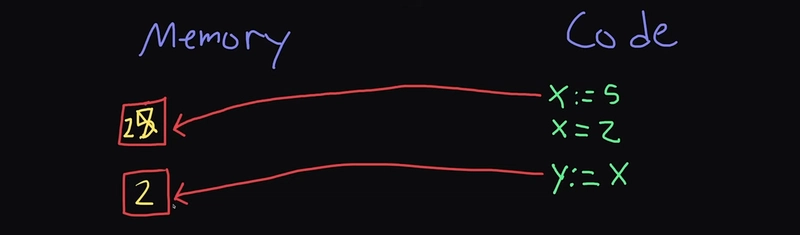

The department had four employees, a budget of $15,000 and a mandate to collect “such facts and statistics as shall show the condition and progress of education” in the country. Despite these limits, the department was attacked as an unconstitutional intrusion on the authority of states and local school systems. A year later, caught in the Southern backlash to Reconstruction, the department was demoted to an Office of Education in the Department of the Interior.

Over the following years, the office operated under different names and in different agencies. Apart from limited forays into educational policy at moments of heightened national anxiety —such as increased funding for science and foreign-language study after the 1957 Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite — education was left to the states.

In the 1960s, however, President Lyndon Johnson introduced multiple programs to improve education for poor students as part of his War on Poverty. The 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act aimed to reduce achievement gaps by supporting disadvantaged students and marked “the first big infusion of federal dollars into day-to-day classroom and school activity.” The 1965 Higher Education Act sought to provide all students access to post-secondary education.

Protection of the civil rights of minorities, women and people with disabilities also became a federal education priority with adoption of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. By offering grants with substantive conditions rather than direct mandates, and by supporting equal opportunity and anti-discrimination programs, the government worked around the constraints of the 10th Amendment.

These new programs required substantial oversight. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act, for example, expanded to encompass almost all school districts, and imposed eligibility requirements intended to foster improved academic performance. In 1979, Congress approved President Jimmy Carter’s proposal to reestablish the Department of Education, despite Republican objections.

Every Republican platform since then has promised to close the department, but, as President Ronald Reagan discovered, there was “very little support” for the idea in Congress. President George W. Bush substantially increased federal education spending with the bipartisan No Child Left Behind Act. In 2009, President Barack Obama launched his Race to the Top initiative, under which the department provided voluntary grants to states to establish charter schools, raise readiness standards and evaluate teachers using student test scores.

The department also initiated income-based student loan payment plans; appropriated more money for Pell Grants, Head Start and other equal-opportunity programs; and put pressure on for-profit colleges to improve student outcomes.

With 4,100 employees, the Department of Education remains the smallest Cabinet-level agency, but it has the sixth-largest budget, roughly $270 billion. That funding, coupled with federal antidiscrimination legislation, gives the department considerable influence on state educational programs, even though states and localities provide 92 percent of public school funds and retain principal control over education.

President Trump’s 2018 proposal to merge the Departments of Education and Labor went nowhere, even though Republicans controlled Congress. In 2023, only half of House Republicans voted to convert ESEA’s Title I funding (which supports low-achieving students in high-poverty schools) into a voucher program.

These days, many Republicans want the department to implement their policies on universal school choice, gender and critical race theory. The GOP platform endorses defunding public schools that “engage in inappropriate political indoctrination” while supporting the promotion of curricula “that teach America’s Founding Principles and Western Civilization” and permitting prayer and Bible reading.

Conservative culture warrior Christopher Rufo advocates deploying “the full weight of the Department of Education and a platoon of right-wing lawyers trying to use all of the statutory and executive authority that they have to reshape higher education.” And Trump has promised to expand school choice, support home-schooling, abolish teacher tenure, eliminate federal funding to schools with vaccine mandates, establish a new entity to credential teachers, end financial support for colleges that engage in “censorship” and forbid schools from teaching students “to hate America” or recognizing any gender identity other than male and female.

The Trump administration may seek to have it both ways. It is drafting an executive order to transfer key functions of the department to other agencies, and Elon Musk’s DOGE staff are looking for ways to cut spending and lay off employees. Meanwhile, Trump is relying on the department to sanction schools that tolerate antisemitism or fail to adopt his policies on race and gender.

Calls to close the Department of Education may serve as a rallying cry for conservatives, but it is far more likely that the new administration will use the department to pursue its agenda in ways that, ironically, will have a much more direct impact on state educational curricula than the equal-opportunity goals pursued by Democrats.

Glenn C. Altschuler is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Emeritus Professor of American Studies at Cornell University. David Wippman is emeritus president of Hamilton College.