Why is Justice Alito so trusting of the Trump administration?

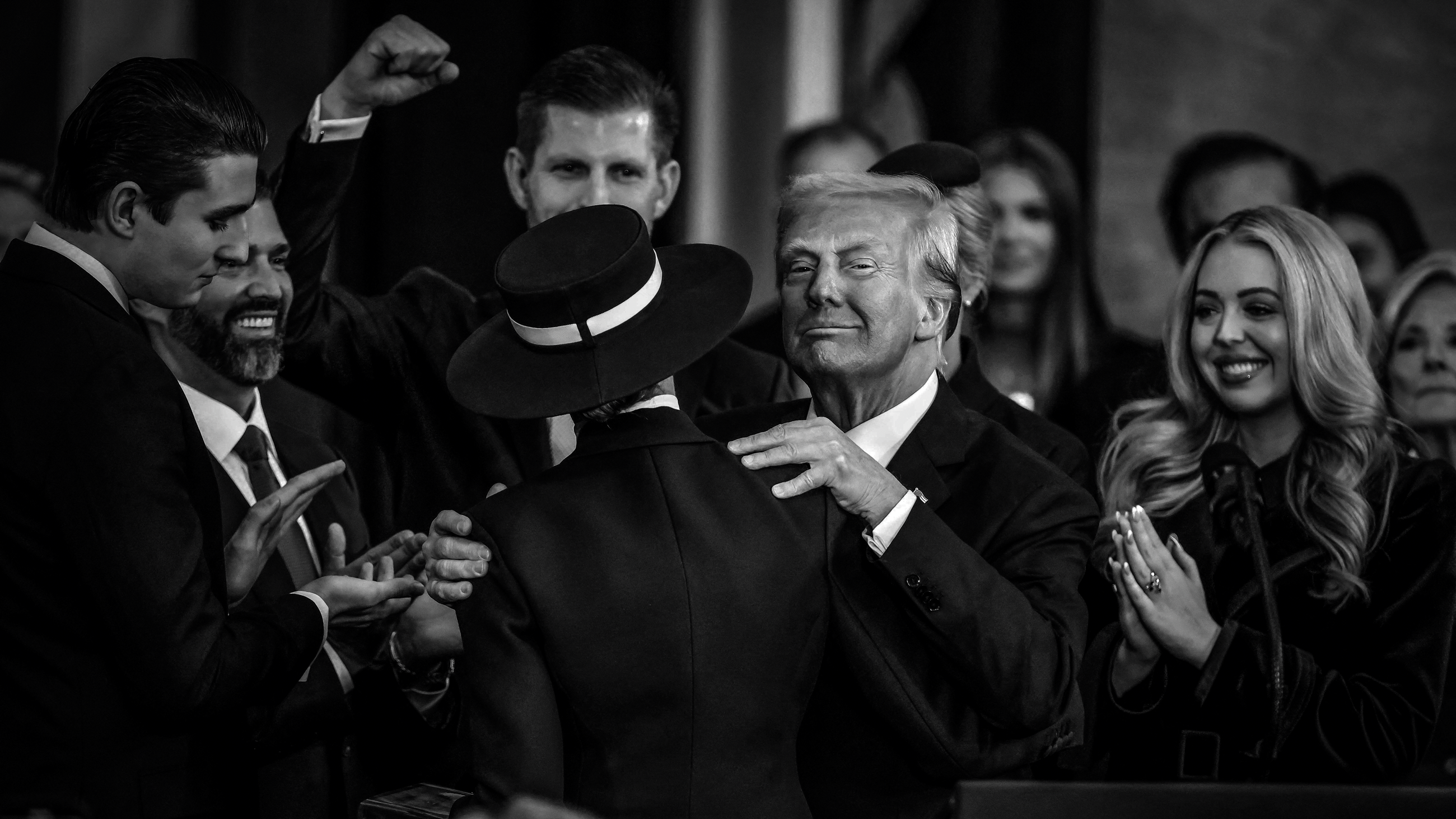

The ordinarily hard-edged jurist strained to take the Trump administration at its word in his dissent from the Supreme Court’s emergency order at 1 a.m. Saturday morning.

Who knew that Justice Samuel Alito was such a trusting person?

The ordinarily hard-edged jurist strained to take the Trump administration at its word in his dissent from the Supreme Court’s emergency order at 1 a.m. Saturday morning prohibiting the Trump administration from deporting a group of Venezuelan migrants under the Alien Enemies Act.

Joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, Alito called the seven-justice majority’s order “hastily and prematurely granted.” The court, he wrote, “had no good reason to think that, under the circumstances, issuing an order at midnight was necessary or appropriate.” The Supreme Court had already declared in an earlier decision that Trump could not deport migrants without giving them an opportunity to contest their deportation in court.

Alito evidently thought it unimaginable that the earlier decision would not be obeyed, despite multiple declarations by the administration that it would do whatever it liked. “Both the Executive and the Judiciary have an obligation to follow the law,” he wrote. “The Executive must proceed under the terms of our order ... and this Court should follow established procedures.”

The American Civil Liberties Union had argued in its application that “numerous Venezuelan nationals currently in the government’s custody in the Northern District of Texas have received notices that they are subject to removal under the [Alien Enemies Act], and further were informed by government officials that they may be removed from the United States as soon as this afternoon or tomorrow. DHS has now publicly announced that AEA removals are imminent.”

Alito claimed that there was “little concrete support” for the allegation of “imminent danger of removal.” He emphasized that “an attorney representing the Government in a different matter ... informed the District Court ... that no such deportations were then planned to occur either yesterday, April 18, or today, April 19.”

But here is what the attorney actually said on April 18: “I've spoken with DHS, they are not aware of any current plans for flights tomorrow, but I have also been told to say that they reserve the right to remove people tomorrow.” That reservation, which Alito omits, changes the meaning dramatically. If I told you that I have no plans to set your house on fire but I reserve the right to do so, would that constitute “concrete support” for your feeling of “imminent danger”? (It has since been reported that buses carrying Venezuelans were headed to the airport on April 18 before they abruptly turned around.)

It is also pertinent that the entire mass deportation effort rests on a factually ridiculous premise. The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 states that in case of “any invasion ... by any foreign nation or government,” the president can deport citizens of that government. Trump declared that a Venezuelan drug cartel had invaded the U.S. with the collusion of its government.

But the government’s own intelligence concluded that there’s no evidence of such collusion, and therefore of any invasion. Trump might as well have claimed an invasion from Mars. This should not elicit confidence in the administration’s claims.

The administration has also boldly misconstrued the high court’s earlier order to “facilitate” the return of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, whom it illegally deported. It read that order in a preposterously grudging way that essentially nullified it. (The White House later posted a declaration on social media that Abrego Garcia is “never coming back.”) The court’s latest decision seems carefully crafted to resist this kind of misreading: “The Government is directed not to remove any member of the putative class of detainees from the United States until further order of this Court.”

Alito is right that there’s a strong presumption against doing what the Supreme Court did. The court, he writes, issues injunctions pending appeal only when “the legal rights at issue are indisputably clear and, even then, sparingly and only in the most critical and exigent circumstances.” But these are critical circumstances, when the administration has already indicated its intention to defy the court. And Alito has in the past been remarkably willing to support such injunctions when they were deployed against Democratic administrations. (The passage just quoted was from an opinion refusing to block a state’s Covid restrictions — a refusal from which Alito dissented.)

It is also notable that the order merely forbade what Alito was sure that Trump would not do. Alito has sometimes been mighty suspicious of government actions that allegedly harmed conservative Christians like himself. He sometimes succumbs to pure tribalism. That is perhaps the best explanation for his uncharacteristically trusting approach to what may be the most lawless administration in American history.

Andrew Koppelman, the John Paul Stevens Professor of Law at Northwestern University, is the author of “Burning Down the House: How Libertarian Philosophy Was Corrupted by Delusion and Greed.”