Trump’s apprenticeship plan could be the best thing he does for the economy

The Trump administration has issued executive orders to promote apprenticeships, which can provide a better education and workforce system. Congress should follow the administration's lead.

President Trump issued a flurry of executive orders last week relating to education and workforce development. Most continued the administration’s predictable attacks on traditional higher education, but one stands out for setting a proactive vision for a better American education and workforce system: the executive order on apprenticeships.

If the administration follows through on this order, it could be the biggest contribution it makes to building a stronger U.S. labor market.

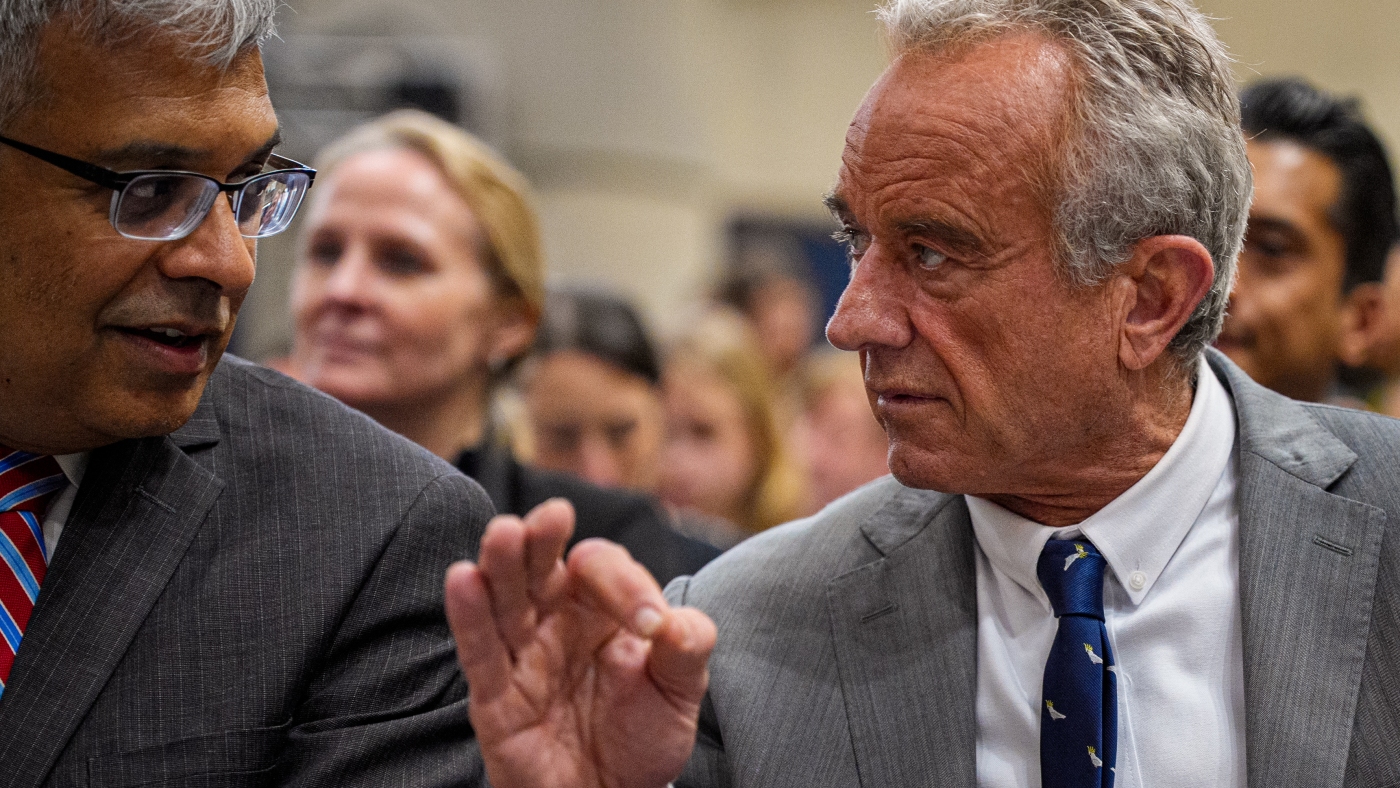

What sets the order apart? It reflects a growing awareness — on both sides of the aisle — that America’s higher education system is broken. Its accompanying fact sheet rails against our “one-size-fits-all approach to workforce preparedness, which previous Administrations promoted as ‘college for all.’” Trumpian rhetoric notwithstanding, the facts don’t lie: according to Bob Lerman, my co-founder at Apprenticeships for America, apprentices get around 2 percent of the funding that college students receive from the federal government.

The order also sets a clear goal and creates a road map to get there. The order calls for a plan to reach 1 million new active apprentices, which while not a huge increase from the 680,000 apprentices currently active in the country, marks the first time an administration has set an actual goal rather than simply continuing to shell out apprenticeship dollars to workforce boards and community colleges hoping for something good to come of it.

The road map to those 1 million apprentices is just as important: the order directs departments to “consolidate and streamline fragmented Federal workforce development programs that are too disconnected from propelling workers into secure, well-paying, and high-need American jobs” and to identify “workforce development and education programs… that are ineffective or otherwise fail to achieve their desired outcomes.”

This is essential because workforce development in the U.S. relies on a fragmented system of state and local workforce development or investment boards, responsible for spending federal and state workforce dollars on “one stop” career centers to help job seekers find jobs. While some of these programs are effective at putting people in jobs, they’re wholly ineffective in putting people in good jobs. And because they’re either speed-to-placement in bad jobs or training programs with few employer and employment connections, none claim strong career launch or economic mobility outcomes.

In contrast, registered apprenticeships are good jobs with clear career paths, the polar opposite of current workforce training programs. This explains why the administration’s accompanying fact sheet bemoans the $4.1 billion spent each year on workforce development and $1.4 billion on career and technical education while “neither of these programs are structured to promote apprenticeships” and why the order directs departments to eliminate or redirect the funding of ineffective programs.

There are further glad tidings in last month’s executive orders — including the one on AI education, which also mentions apprenticeship. By emphasizing registered apprenticeships, Trump signaled the end of so-called "industry-recognized apprenticeships" that had become a distraction and dead-end in his first term.

Second, the AI executive order correctly calls out the importance of apprenticeship intermediaries and suggests allocating funding to intermediaries “to engage industry organizations and employers and facilitate the development of Registered Apprenticeship programs in AI-related occupations.”

Third, the AI order suggests developing federal program standards for apprenticeships — a decades-long deficit that has distinguished and hobbled American apprenticeships — “enabling individual employers to adopt the standards without requiring individual registry.” This last point suggests the administration is aware of the heavy burden of registration, in stark contrast to the Biden administration which sought to add dozens of additional and unnecessary regulatory requirements. So look for further action on rationalizing registration for the tech, health care and financial services apprenticeships that don’t require safety protocols appropriate for the building trades.

Whether 2025 proves to be an annus mirabilis for apprenticeship now depends on Congress. The executive orders and funding cuts throw down the gauntlet to an institution that has been woefully out of step. The bipartisan American Apprenticeships Act, introduced this March, has looked the same for nearly a decade, providing competitive grants to states and other changes that shouldn’t be on anyone’s top 10 list for apprenticeship growth.

In the House, serial efforts to amend the National Apprenticeship Act have focused on nitpicky policy issues that, while not unimportant (e.g., better data sharing and increased apprenticeship opportunities for people who face barriers to employment), wouldn’t do much to scale apprenticeship infrastructure or convince employers to hire apprentices. This may be an area where the legislative branch would do well to align better with the priorities identified by the executive.

The arguments for apprenticeship are many: equity (earn-and-learn pathways are accessible to everyone, regardless of background or resources); employment (apprenticeships uniquely close both skill and experience gaps); efficiency (cheaper than college or train-and-pray programs); and because the earn-and-learn infrastructure that will emerge from investing in apprenticeship will support the full spectrum of work-based learning that college graduates will need if they want to get good first jobs in the age of AI.

Then there’s balance. More than any other country, we’ve gone all-in on classroom-based, tuition-based, debt-based career launch infrastructure while dramatically underinvesting in earn-and-learn pathways. We’ve unfairly discriminated against young adults uninterested in or unable to sit in classrooms and pay tuition.

And while organizing apprenticeships and involving employers from the start are harder than just shoving students in a classroom, unless we do the work, things aren't going to get any better. These executive orders are just the first step in doing that work. But they’re a signal that this administration may know something about the power of apprenticeships that its predecessors didn’t.

Ryan Craig is the author of “College Disrupted, A New U: Faster and Cheaper Alternatives to College,” and “Apprentice Nation: How the ‘Earn and Learn’ Alternative to Higher Education Will Create a Stronger and Fairer America.” He is managing director at Achieve Partners, which is investing in the future of learning and earning.