Trump wants more ships? Korea stands ready to help build them.

Korea is ready to become a cornerstone of a stronger, more mutually beneficial alliance system

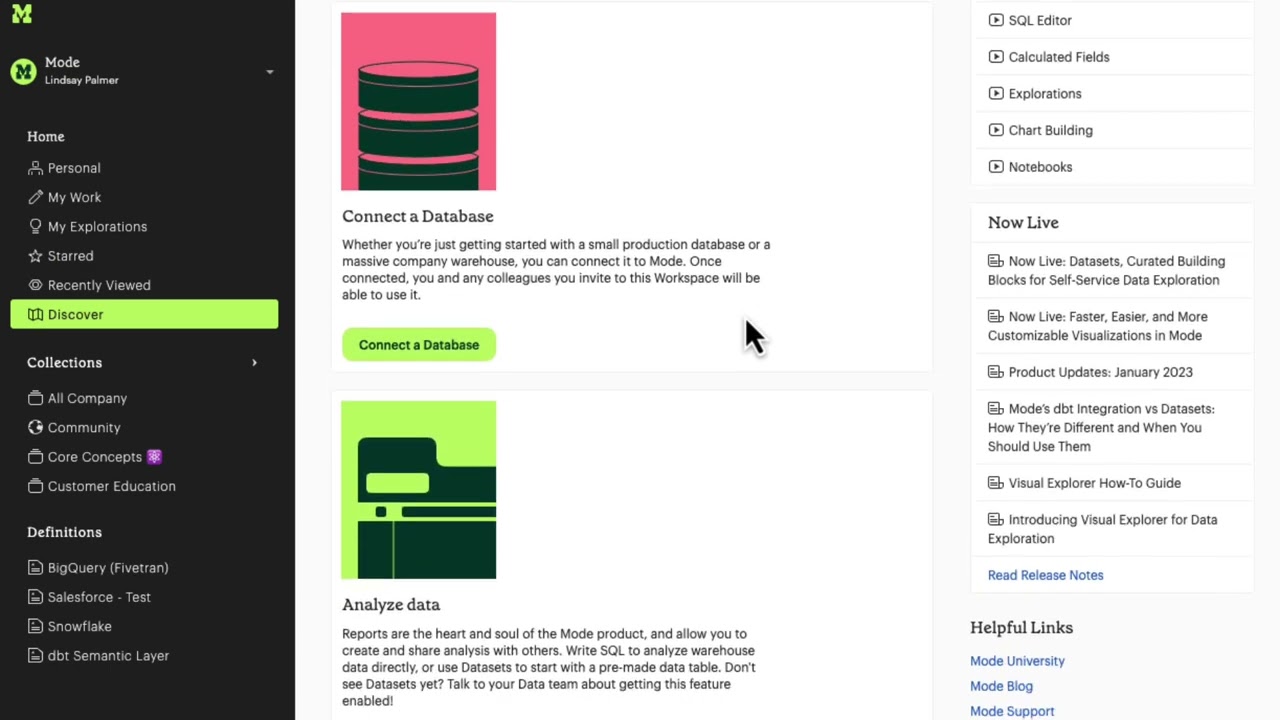

The White House issued an executive order last month to restore America's maritime dominance, a move that went largely unnoticed amid the larger frenzy of actions being taken in the Trump administration’s first 100 days. Despite this low profile, the order, part of a series of actions that include the creation of a White House Shipbuilding Council and the introduction of the bipartisan U.S. SHIPS Act, is of critical importance to rebuilding a key pillar of American national security: the U.S. shipbuilding industry.

Why the sudden bipartisan determination to revive American shipbuilding? When Japanese bombs dropped on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. responded to a far more experienced naval adversary by outbuilding it. In 1943, only three aircraft carriers were under construction in Japanese shipyards, while 22 were being built in the U.S. Though shipbuilding alone did not determine World War II, it proved that superior industrial capacity was a critical enabler of success in prolonged great power conflicts.

Today, that capacity has largely disappeared.

Over 80 percent of U.S. shipyards have closed since the 1980s, and the U.S. builds fewer than five ships per year. Production has moved overseas to America’s number one competitor, China. Chinese shipbuilding capacity is now 232 times greater than our own. China's navy is on track to have 460 vessels by 2030, dwarfing the American Navy’s 295 ships.

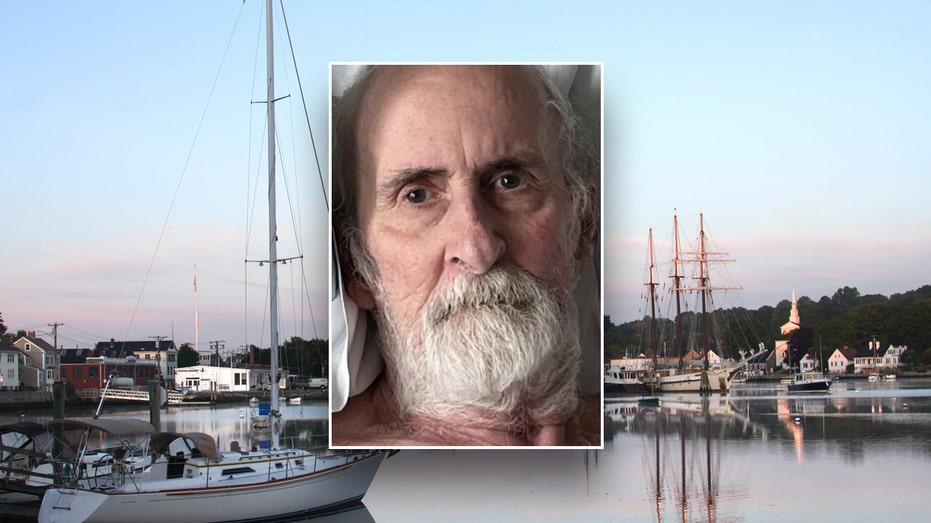

In today’s climate of renewed great power competition, Republicans and Democrats alike are racing to rebuild this critical industry. While their efforts rely largely on supporting industry champions at home, the solution may lie with a key Asian ally whose shipyards are among the world’s most productive — one that stands ready to help America rebuild its maritime power. To close the ship gap, revive American industry and breathe new life into one of our oldest alliances, the United States should pursue a strategic shipbuilding partnership with South Korea.

As a U.S. ally since 1953, the Republic of Korea already hosts 28,500 American troops in the Indo-Pacific. Despite this, the alliance's economic and industrial potential remains underdeveloped. China is the world’s largest shipbuilding nation, but Korea is the second largest. Internationally recognized for its sophistication, productivity and professionalism, Korean firms such as HD Hyundai, Hanwha Ocean and Samsung Heavy Industries have productivity rates two to three times higher than competing American firms, and produce commercial and naval vessels alike. In 2025 alone, South Korea accounted for 27 percent of global ship orders.

This is exactly the kind of partner the U.S. needs.

A new partnership could operate through a dual-shore approach that transforms the traditional U.S.-South Korea military alliance into an integrated strategic industrial base.

The first shore is the United States. In 2024, Hanwha Ocean acquired Philly Shipyard, marking the first Korean ownership of an American shipbuilding facility. Washington should expand this model and negotiate the construction or transfer of additional shipyards to be operated by Korean firms, either independently or as joint ventures with American shipbuilders such as HII or General Dynamics.

This approach would expand production capacity, accumulate industry best practices and create new jobs across America. These shipyards could produce both naval combatants and commercial vessels, presenting Korean firms with new revenue streams, international shipping companies greater supply chain resiliency, American communities new jobs, and the U.S. Navy more ships.

The second shore is South Korea. Hyundai Heavy Industries announced in April that the Korean firm could build up to five Aegis destroyers per year for the U.S. Navy if bilateral cooperation is formalized. While new shipyards in America are getting up and running, the U.S. should lean more on its allies to sustain its maritime strength.

Washington should formalize agreements with capable Korean shipyards to procure naval combatants and secure access for maintenance, repair and resupply missions in the region. Hanwha successfully rendered these services to the U.S. Naval Ship Wally Schirra in March, proving the arrangement’s feasibility. By institutionalizing production and servicing contracts, Korean shipbuilders can help expand the American fleet while sustaining ongoing forward-deployed operations.

President Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs against South Korea, despite the two countries’ free trade agreement and long-standing relations, put the U.S.-Korea alliance on shaky ground. That said, it also made clear that allies benefiting from American security guarantees must make visible contributions to core U.S. interests. This dual-shore shipbuilding strategy is a model of how an ally can do just that.

For one, this initiative would turn a conventional defense treaty into a fully-fledged industrial alliance, leveraging both countries’ military, technological and manufacturing strengths to produce a maritime force capable of defending shared interests. Second, it would put the alliance on firmer ground by broadening the coalition of invested stakeholders. While a mutual defense treaty is at the mercy of world leaders, an industrial alliance supporting thousands of jobs in communities across both countries is far more resilient. By tying foreign policy objectives to local political interests, both capitals can strengthen and diversify the buy-in to this alliance.

Today, American allies around the world worry that the U.S. has given up on alliances. By transforming the U.S.-South Korea alliance, Washington has the chance to send a clear and critical signal: alliances must deliver, and they can deliver when built around mutual interest and resilience.

Korea is ready to become a cornerstone of a stronger, more mutually beneficial alliance system; it is primed to help carry the weight of some of the most pressing items on America’s foreign and domestic political agendas, bringing jobs and security back to America. The burden is on Washington to recognize the urgency and potential of the moment and set sail for that stronger, safer future.

Arjun Akwei is a Schwarzman Scholar and a former research associate at Harvard University’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Jinwan Park is a Nonresident James A. Kelly Korea Fellow at Pacific Forum and a nonresident fellow at the European Centre for North Korean Studies at the University of Vienna.