The odd couple: Trump and Starmer make nice, for now

Avoiding pitfalls is far short of concrete achievements.

Keir Starmer and his advisers must be breathing audible sighs of relief.

The British prime minister traveled to Washington for his first White House visit since President Trump’s inauguration in unpromising circumstances. Over recent weeks, the president had initiated talks with Russia over Ukraine, bypassing Europe and the government in Kyiv. Vice President JD Vance had accused Europe of suppressing free speech and ignoring mass migration. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth had announced that “safeguarding European security must be an imperative for European members of NATO.”

Starmer can return to London with a sense of achievement. Trump lauded the U.K. and its prime minister as “a very special place and ... a special man,” and his mood was more positive than many had feared.

The prime minister deployed a coup de theatre early on, producing — literally from his inside pocket — a letter from King Charles III inviting Trump for a U.K. state visit. Starmer sailed close to parodying his host when saying, “This is really special ... this has never happened before ... this is unprecedented.” Trump undertook a state visit in June 2019, and he will be the first elected politician of the modern era to be invited for a second.

Two potentially contentious issues — Starmer’s eagerness to work more closely with the European Union and his government’s agreement to cede sovereignty of the British Indian Ocean Territory to Mauritius — barely registered. The latter was potentially sensitive, as the territory is home to the strategically vital U.S. airbase and naval facility on Diego Garcia, but Trump remarked nonchalantly that he was “inclined to go along with it.”

There was more: Trump indicated that a U.S.-U.K. trade deal could be made “very quickly,” and called Starmer a “tough negotiator,” high praise from the ostensible author of “The Art of the Deal.” While the president still intends to impose tariffs on imports from the EU, in Britain’s case he said, “I think we could very well end up with a real trade deal where the tariffs wouldn’t be necessary. We’ll see.”

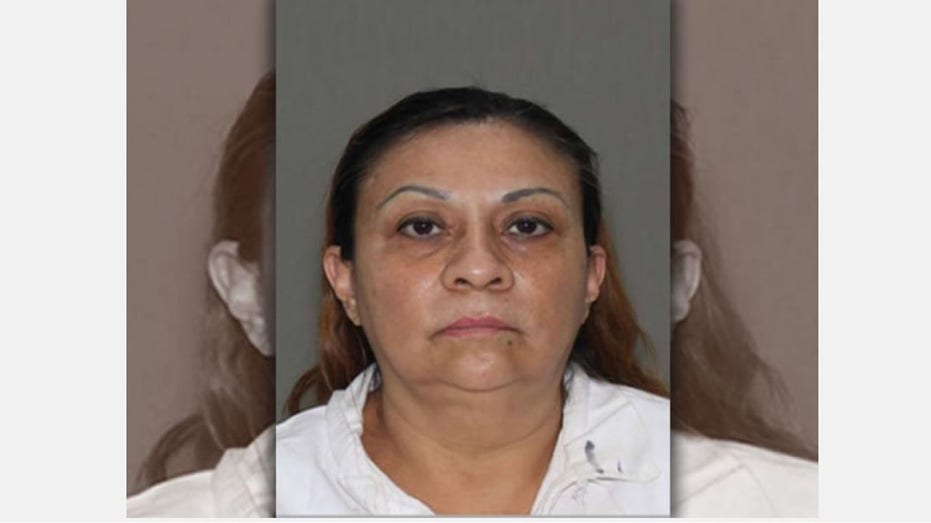

Things could have gone much worse. Trump and Starmer are almost a sitcom-ready odd couple, albeit without the humor: the brash, freewheeling real estate mogul and the pedantic, uncharismatic human rights lawyer. Starmer is a left-wing progressive, swimming against Europe’s electoral tide, while Trump’s rudimentary nationalism and authoritarian instincts place him squarely on the right. Yet the tone was cordial and without significant friction. Perhaps Britain’s new ambassador in Washington, Peter Mandelson, had carried out successful groundwork in preparation.

Starmer’s team should be aware, nonetheless, that avoiding pitfalls is far short of concrete achievements. Trump did not agree to provide what the prime minister calls a “backstop” for any monitoring force in a post-conflict Ukraine, which would probably involve American aerial reconnaissance and logistical support and, in the last resort, air power to punish infringements of a peace accord. Instead, the president suggested that a deal between the U.S. and Ukraine on minerals would act as a kind of “backstop,” as “nobody will play around” if there are American workers on the ground. That is not what Starmer has in mind.

There was no significant course change in foreign policy terms. This was never a likely outcome, but the strategic context remains what it was: Trump wants a swift resolution to the war in Ukraine and is willing to concede a lot of ground to Vladimir Putin to get it.

Beyond that, America’s involvement in European security will diminish, and the nations of Europe will have to dig deeper into their own treasuries to protect themselves. Starmer preempted this by announcing on Feb. 25 that the U.K. would increase defense spending to 2.5 percent of GDP by 2027, raiding its international aid budget for the necessary resources. (The development minister, Anneliese Dodds, thoughtfully waited until after the summit to tender her resignation).

The unexpected sequel that has disrupted everything was Trump’s chaotic encounter the following day with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Goaded by a boorish Vance that he should “just say thank you,” Zelensky attempted to correct some wildly inaccurate propositions Trump had made, and was told he was not being respectful. He was ejected from the White House not long afterwards, the proposed deal with the U.S. on access to mineral resources unsigned.

Starmer welcomed Zelensky to London the following day and repeated his declarations of British support for Ukraine, telling him, “We stand with you and Ukraine for as long as it may take.” Starmer sees himself as a potential bridge between the U.S. on the one hand and Europe and Ukraine on the other, but Trump’s view of that role remains to be seen.

For Britain as the junior partner in the relationship, whether it is “special” or not, there is the underlying and ongoing challenge of Trump’s utter unpredictability. Not only is it extremely difficult to foresee his next move, it is perilous to put much weight on his public pronouncements, as they can be amended, walked back or flatly denied according to his mood.

In Hollywood, they say that you are only as good as your last picture. It is an idea Starmer should bear in mind. This visit was a moderate success, but given the pace of events and Trump’s mercurial nature, the special relationship is only as good as its last meeting.

Eliot Wilson is a freelance writer on politics and international affairs and the co-founder of Pivot Point Group. He was senior official in the U.K. House of Commons from 2005 to 2016, including serving as a clerk of the Defence Committee and secretary of the U.K. delegation to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.