The life of a dairy cow

At Vox, I specialize in writing and editing all sorts of stories about animal agriculture and the future of food, from the strange ritual of eating turkeys on Thanksgiving to the policy debates around the fate of mother pigs in the pork industry. But the lives of America’s 9.4 million dairy cows have always been […]

At Vox, I specialize in writing and editing all sorts of stories about animal agriculture and the future of food, from the strange ritual of eating turkeys on Thanksgiving to the policy debates around the fate of mother pigs in the pork industry. But the lives of America’s 9.4 million dairy cows have always been especially close to my heart, and to many people who care about farm animals, for reasons that will become clear as you read this comic. I’d written a bit about dairy cows before, but to truly do the story justice, I knew I needed to narrate and illustrate, in depth, a dairy cow’s life from birth to death (and even then, there was so much from my research that had to be left on the cutting-room floor). Once you really see it, it’s impossible to look at milk the same way again.

Sources and further reading:

• Spoiled: The Myth of Milk as Superfood, by Anne Mendelson

• The Cow with Ear Tag #1389, by Kathryn Gillespie

• Americans are drinking more cow’s milk. Here’s why that’s a problem. (Vox)

• 9 charts that show US factory farming is even bigger than you realize (Vox)

• Big Milk has taken over American schools (Vox)

• The truth about organic milk (The Atlantic)

• What happens at livestock auctions? (Vox)

• “I just want to leave with the calf”: The US activist befriending farmers (The Guardian)

• Newborn dairy calves endure long, grueling journeys across the United States (Animal Welfare Institute)

• Regrouping induces anhedonia-like responses in dairy heifers (JDS Communications, a journal of the American Dairy Science Association)

• Don’t mind milk? The role of animal suffering, speciesism, and guilt in the denial of mind and moral status of dairy cows (Food Quality and Preference journal)

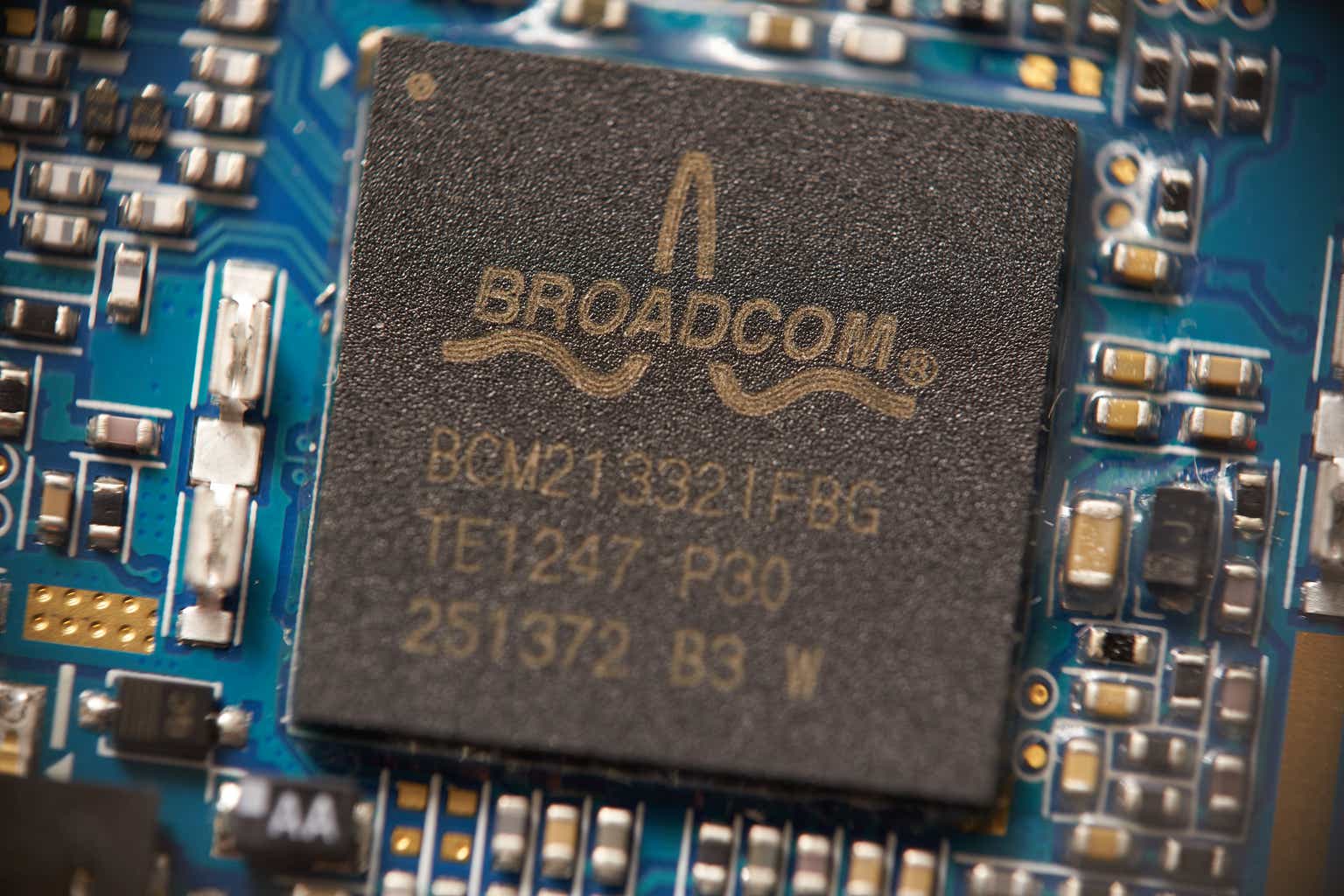

_Igor_Mojzes_Alamy.jpg?#)