The Atlantic: A history of protest at Columbia University

This article in The Atlantic by Frank Foer, former editor of The New Republic (and who attended Columbia) gives a thorough and excellent summary of the history of antisemitic protests at the school. You can probably access it for free by clicking on the headline below, or you can find the article archived here. It’s … Continue reading The Atlantic: A history of protest at Columbia University

This article in The Atlantic by Frank Foer, former editor of The New Republic (and who attended Columbia) gives a thorough and excellent summary of the history of antisemitic protests at the school. You can probably access it for free by clicking on the headline below, or you can find the article archived here. It’s well worth reading.

You can read the whole thing for yourself, but I’ll give a few quotes. It begins with the recent anti-Semitism at Columbia when Avi Shilon’s class on the history of modern Israel was interrupted by four disruptive pro-Palestinian protestors, two of whom have been expelled and another under investigation. This, however, is only a small part of the anti-Israel and antisemitic atmosphere at that toxic school, which is cleaning up its act only since the Trump administration took away $400 million in federal funds. (Note, however, that this kind of threat could spread throughout U.S. colleges, and that Columbia also detained, probably unlawfully, ex-student Mahmoud Khalif, who may have only been exercising freedom of speech):

Over the many months of that [Israel/Hamas] war, Columbia was the site of some of America’s most vitriolic protests against Israel’s actions, and even its existence. For two weeks last spring, an encampment erected by anti-Israel demonstrators swallowed the fields in the center of the compact Manhattan campus. Nobody could enter Butler Library without hearing slogans such as “Globalize the intifada!” and “We don’t want no Zionists here!” and “Burn Tel Aviv to the ground!” At the end of April, students, joined by sympathizers from outside the university gates, stormed Hamilton Hall—which houses the undergraduate-college deans’ offices—and then battled police when they sought to clear the building. Because of the threat of spiraling chaos, the university canceled its main commencement ceremony in May.

. . .Over the past two years, Columbia’s institutional life has become more and more absurd. Confronted with a war on the other side of the world, the course of which the university has zero capacity to affect, a broad swath of the community acted as if the school’s trustees and administrators could determine the fate of innocent families in Gaza. To force the university into acceding to demands—ending study abroad in Israel, severing a partnership with Tel Aviv University, divesting from companies with holdings in Israel––protesters attempted to shut down campus activity. For the sake of entirely symbolic victories, they were willing to risk their academic careers and even arrest.

Because the protesters treated the war as a local issue, they trained their anger on Jewish and Israeli students and faculty, including Shilon, some of whom have been accused of complicity with genocide on the basis of their religious affiliation or national origin. More than any other American university, Columbia experienced a breakdown in the fabric of its community that demanded a firm response from administrators—but these administrators tended to choke on their own fears.

Many of the protesters followed university rules governing demonstrations and free expression. Many others did not. Liberal administrators couldn’t or wouldn’t curb the illiberalism in their midst. By failing to discipline protesters who transgressed university rules, they signaled that disrupting classrooms carried no price. By tolerating professors who bullied students who disagreed with them, they signaled that incivility and even harassment were acceptable forms of discourse.

Columbia’s invertebrate President (now ex-President) Minouche Shafik set up an antisemitism task force, which gathered tons of examples of antisemitic behavior. On top of that, four Columbia deans were photographed making fun of Jews on their phones as they watched a panel on Jewish life at Columbia (the deans are all gone now). The main promoter of all the student activity was Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD), the group to which Khalil belonged. It’s a big group—and a nasty one:

A month later, at the beginning of the academic year, the task force published a damning depiction of quotidian student life. An especially powerful section of the report described the influence of Columbia University Apartheid Divest, the organizer of the anti-Israel protests. CUAD was a coalition of 116 tuition-supported, faculty-advised student groups, including the university mariachi band and the Barnard Garden Club.

CUAD doesn’t simply oppose war and occupation; it endorses violence as the pathway to its definition of liberation. A year ago, a Columbia student activist told an audience watching him on Instagram, “Be grateful that I’m not just going out and murdering Zionists.” At first, CUAD dissociated itself from the student. But then the group reconsidered and apologized for its momentary lapse of stridency. “Violence is the only path forward,” CUAD said in an official statement. That wasn’t a surprising admission; its public statements regularly celebrate martyrdom.

Foer notes the history of keeping Jews out of Columbia, a history that had largely waned when Foer attended the University but was later exacerbated by the work of Edward Said and his book Orientalism. I found this bit interesting:

The story of American Jewry can be told, in part, by the history of Columbia’s admissions policy. At the turn of the 20th century, when entry required merely passing an exam, the sons of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe began rushing into the institution. By 1920, Columbia was likely 40 percent Jewish. This posed a marketing problem for the school, as the children of New York’s old Knickerbocker elite began searching out corners of the Ivy League with fewer Brooklyn accents.

To restore Anglo-Saxon Protestant demographic dominance, university president Nicholas Murray Butler invented the modern college-application process, in which concepts such as geographic diversity and a well-rounded student body became pretexts to weed out studious Jews from New York City. In 1921, Columbia became the first private college to impose a quota limiting the number of Jews. (In the ’30s, Columbia rejected Richard Feynman, who later won a Nobel Prize in physics, and Isaac Asimov, the great science fiction writer.) Columbia, however, was intent on making money off the Jews it turned away, so to educate them, it created Seth Low Junior College in Brooklyn, a second-rate version of the Manhattan institution.

Only after World War II, when America fought a war against Nazism, did this exclusionary system wither away.

Shafik’s task force found powerful evidence of a plague of antisemitism at Columbia, but when the task force handed its report to Columbia’s university senate, peopled by pro-Palestinian activists who wanted to be on the Senate, the report more or less died, for the faculty simply didn’t want the report given official approval. (It’s Columbia’s faculty that intensifies the atmosphere of Jew- and Israel hatred.) Almost no students were ever punished, even the ones who broke into Hamilton Hall, and this leniency towards rule-breaking, pro-Palestinian protestors seems widespread in American universities, even my own—a fact about which I’ve wailed loudly.

Foer accepts the antisemitism revealed by the task force, but also criticizes Trump’s heavy handed treatment of the university which, to be sure, may be the only thing that will cause Columbia to take action. (Remember, the University Senate tried to quash the task force’s findings.) And Foer has no truck with the treatment of Khalil.

But make no mistake about it: the atmosphere of antisemitism lingers, since it was largely promoted by Columbia’s (and Barnard’s) faculty, and it’s so bad that were I a Jewish parent, I would send my kids anywhere but Columbia—even to Harvard! The litany of antisemitic incidents is much longer than I’ve mentioned here, and that’s one reason Foer’s article is worth reading. Nevertheless, he ends on an upbeat note.

The indiscriminate, punitive nature of Trump’s meddling may unbalance Columbia even further. A dangerous new narrative has emerged there and on other campuses: that the new federal threats result from “fabricated charges of antisemitism,” as CUAD recently put it, casting victims of harassment as the cunning villains of the story. In this atmosphere, Columbia seems unlikely to reckon with the deeper causes of anti-Jewish abuse on its campus. But in its past—especially in its history of overcoming its discriminatory treatment of Jews—the institution has revealed itself capable of overcoming its biases, conscious and otherwise, against an excluded group. It has shown that it can stare hard at itself, channel its highest values, and find its way to a better course.

I cannot share his optimism.

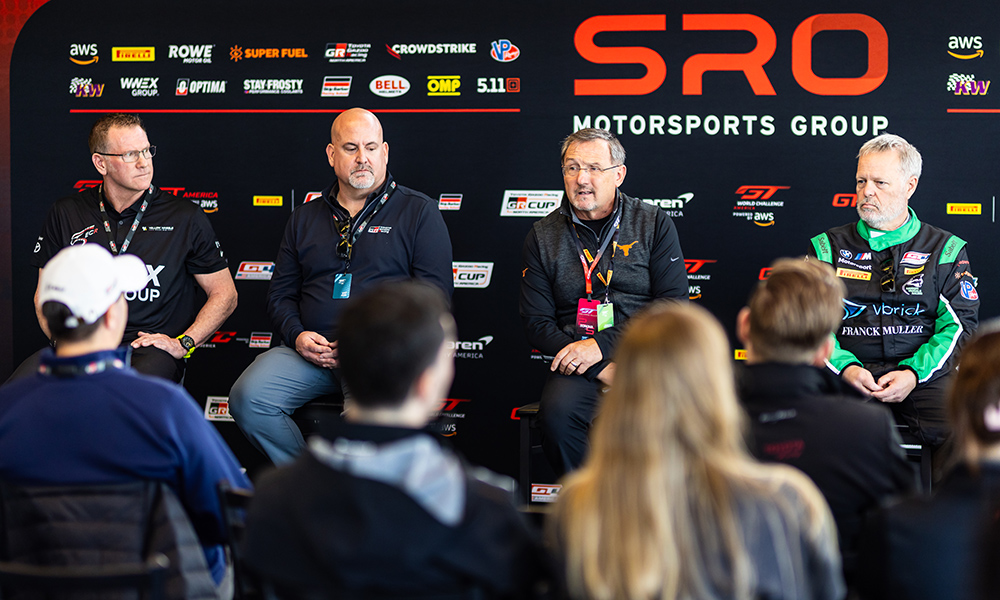

CODA: If you want to see how bad things were at Columbia, have a look at this thread reader recounting the pro-Palestinian break-in into Hamilton Hall, where Columbia’s administration is housed (h/t Jez). It starts this way, and there are a lot of photos (the ones shown are from Getty images in the NY Post article).