People weigh in on the meaning of life

In 2013, I posed some questions to readers about the meaning of life, and there were a lot of responses (373 of them!). To quote part of my post: Here’s survey I’m taking to see whether a theory I have, which is mine, bears any resemblance to reality. Here are two questions I’d like readers … Continue reading People weigh in on the meaning of life

In 2013, I posed some questions to readers about the meaning of life, and there were a lot of responses (373 of them!). To quote part of my post:

Here’s survey I’m taking to see whether a theory I have, which is mine, bears any resemblance to reality. Here are two questions I’d like readers to answer in the comments. Here we go:

If a friend asked you these questions, how would you answer them?

1.) What do you consider the purpose of your life?

2.) What do you see as the meaning of your life?

There was general agreement that the meaning and purpose of life is self-made: there was no intrinsic meaning or purpose. Only religious people think there’s a pre-made meaning and purpose, and it’s always to follow the dictates of one’s god or faith. And there aren’t too many believers around here.

Now the Guardian has an article posing the same question, but asking 15 different people, many of them notables. The answers vary, and I’ll give a few (click the screenshot below to see the article). As Reader Alan remarked after reading the Guardian piece and sending me the link, “No one mentions God and none seem to have a God shaped hole in their lives.”

So much for Ross Douthat and what I call “The New Believers” to go along with “The New Atheists.” The New Believers I see as smart people who have thrown in their lot with superstition and unevidenced faith; they include Doubthat, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Jordan Peterson, and, apparently, the staff of The Free Press.

Bailey’s intro:

Like any millennial, I turned to Google for the answers. I trawled through essays, newspaper articles, countless YouTube videos, various dictionary definitions and numerous references to the number 42, before I discovered an intriguing project carried out by the philosopher Will Durant during the 1930s. Durant had written to Ivy League presidents, Nobel prize winners, psychologists, novelists, professors, poets, scientists, artists and athletes to ask for their take on the meaning of life. His findings were collated in the book On the Meaning of Life, published in 1932.

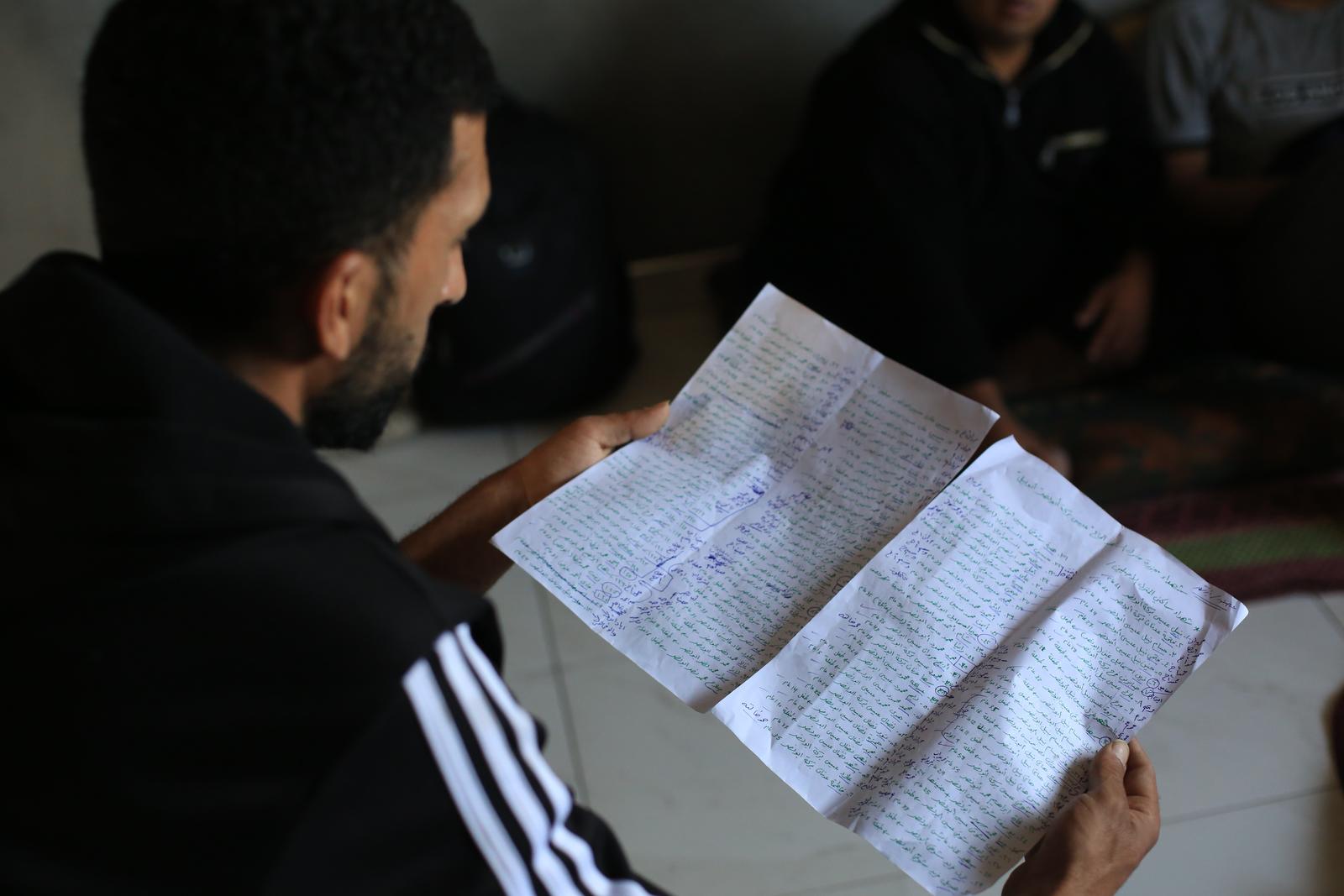

I decided that I should recreate Durant’s experiment and seek my own answers. I scoured websites searching for contact details, and spent hours carefully writing the letters, neatly sealing them inside envelopes and licking the stamps. Then I dropped them all into the postbox and waited …

Days, and then weeks, passed with no responses. I began to worry that I’d blown what little money I had on stamps and stationery. Surely, at least one person would respond?

. . . . . What follows is a small selection of the responses, from philosophers to politicians, prisoners to playwrights. Some were handwritten, some typed, some emailed. Some were scrawled on scrap paper, some on parchment. Some are pithy one-liners, some are lengthy memoirs. I sincerely hope you can take something from these letters, just as I did.

And his question:

I am currently replicating Durant’s study, and I’d be most appreciative if you could tell me what you think the meaning of life is, and how you find meaning, purpose and fulfilment in your own life?

A selection of my favorites:

Hillary Mantel, author (I’m reading her Wolf Hall at the moment; it won the Booker Prize):

I’ve had your letter for a fortnight, but I had to think about it a bit. You use two terms interchangeably: “meaning” and “purpose”. I don’t think they’re the same. I’m not sure life has a meaning, in the abstract. But it can have a definite purpose if you decide so – and the carrying through, the effort to realise the purpose, makes the meaning for you.

It’s like alchemy. The alchemists were on a futile quest, we think. There wasn’t a philosopher’s stone, and they couldn’t make gold. But after many years of patience exercised, the alchemist saw he had developed tenacity, vision, patience, hope, precision – a range of subtle virtues. He had the spiritual gold, and he understood his life in the light of it. Meaning had emerged.

I’m not sure that many people decide to have a purpose, with the meaning emerging later, but some do. A doctor or nurse, for example, might see their purpose to save lives or help the ill. I suppose I could say my purpose was to “do science,” but that’s only because that’s what I enjoyed, and I didn’t see doing evolutionary genetics it as a “purpose.”

Kathryn Mannix, palliative care specialist. I always like to see what those who take care of the dying say about their patients, as I think I could learn about how to live from those at the end of their lives. Sadly, the lesson is always the same: “Live life to the fullest.” That is not so easy to do! Her words:

Every moment is precious – even the terrible moments. That’s what I’ve learned from spending 40 years caring for people with incurable illnesses, gleaning insights into what gives our lives meaning. Watching people living their dying has been an enormous privilege, especially as it’s shown me that it isn’t until we really grasp the truth of our own mortality that we awaken to the preciousness of being alive.

Every life is a journey from innocence to wisdom. Fairy stories and folk myths, philosophers and poets all tell us this. Our innocence is chipped away, often gently but sometimes brutally, by what happens to us. Gradually, innocence is transformed to experience, and we begin to understand who we are, how the world is, and what matters most to us.

The threat of having our very existence taken away by death brings a mighty focus to the idea of what matters most to us. I’ve seen it so many times, and even though it’s unique for everyone, there are some universal patterns. What matters most isn’t success, or wealth, or stuff. It’s connection and relationships and love. Reaching an understanding like this is the beginning of wisdom: a wisdom that recognises the pricelessness of this moment. Instead of yearning for the lost past, or leaning in to the unguaranteed future, we are most truly alive when we give our full attention to what is here, right now.

Whatever is happening, experiencing it fully means both being present and being aware of being present. The only moment in our lives that we can ever have any choice about is this one. Even then, we cannot choose our circumstances, but we can choose how we respond: we can rejoice in the good things, relax into the delightful, be intrigued by the unexpected, and we can inhabit our own emotions, from joy to fear to sorrow, as part of our experience of being fully alive.

I’ve observed that serenity is both precious and evanescent. It’s a state of flow that comes from relaxing into what is, without becoming distracted by what might follow. It’s a state of mind that rests in appreciation of what we have, rather than resisting it or disparaging it. The wisest people I have met have often been those who live the most simply, whose serenity radiates loving kindness to those around them, who have understood that all they have is this present moment.

That’s what I’ve learned so far, but it’s still a work in progress. Because it turns out that every moment of our lives is still a work in progress, right to our final breath.

This is more or less what Sam Harris has to say in many of his meditation “moments.” Sadly, living each day to the fullest is hard to do, at least for me.

Gretchen Rubin, author and happiness expert. She’s written and studied a lot about happiness, so she should know:

In my study of happiness and human nature, and in my own experiences, I have found that the meaning of life comes through love. In the end, it is love – all kinds of love – that makes meaning.

In my own life, I find meaning, purpose and fulfilment by connecting to other people – my family, my friends, my community, the world. In some cases, I make these connections face-to-face, and in others, I do it through reading. Reading is my cubicle and my treehouse; reading allows me better to understand both myself and other people.

I agree with her 100% on reading, and there are many times that I’d rather be curled up with a good book than socializing. However, we evolved in small groups of people and clearly are meant to be comfortable in these groups and bereft without them. Though we can overcome that, evolution tells us a bit about what kinds of things we should find fulfilling.

Matt Ridley, science writer.

There never has been and never will be a scientific discovery as surprising, unexpected and significant as that which happened on 28 February 1953 in Cambridge, when James Watson and Francis Crick found the double-helix structure of DNA and realised that the secret of life is actually a very simple thing: it’s infinite possibilities of information spelled out in a four-letter alphabet in a form that copies itself.

I think he fluffed the question, which is given above. He says nothing about how he finds meaning, fulfillment, and purpose in his own life. Nothing!

One more:

Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit:

What is the meaning of life? I can honestly say: I have no idea. But I write this in London, where I am visiting with my wife and two boys. And they are healthy and safe, and (mostly) happy, and there’s joy in watching their delights: a clothing stall with a jacket they’ve long wanted; the way the double-decker bus carries us above the fray; a monument to scientific discoveries beside a flower garden and goats.

I’m surrounded by evidence – of the blitz, D-day, colonies despoiled, JFK and MLK and 9/11 – that all could be otherwise. I hear about bombs falling on innocents, an uncertain election, a faltering climate, and many of us lacking the will (or charity) to change.

Yet still I marvel that we flew here in under 12 hours – while my ancestors required months and tragedies to transit in reverse – and that I will send this note simply by hitting a button, and we can love whomever we want, and see and speak to them at any hour, and a pandemic did not end my life, did not kill my children’s dreams, did not make society selfish and cruel.

And, for now, that’s enough. I do not need to know the meaning of life. I do not need to know the purpose of it all. Simply breathing while healthy and safe, and (mostly) happy is such a surprising, awe-inducing, humbling gift that I have no right to question it. I won’t tempt fate. I won’t look that gift horse in the mouth. I’ll simply hope my good fortune continues, work hard to share it with others, and pray I will remember this day, this moment, if my luck fades .